|

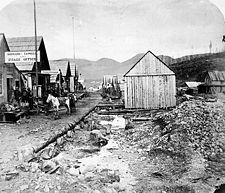

Barnard's Express Barnard's Express, later known as the British Columbia Express Company or BX, was a pioneer transportation company that served the Cariboo and Fraser-Fort George regions in British Columbia, Canada from 1861 until 1921. The company's beginnings date back to the peak of the Cariboo Gold Rush when hordes of adventurers were descending on the Cariboo region. There was a great demand for the transportation of passengers to and from the goldfields, as well as the delivery of mining equipment, food supplies and mail between Victoria and Barkerville. The stage years The first express service offered on the Cariboo Road was operated by William Ballou in 1858. Others soon followed, usually one or two man operations where the proprietor himself packed the express goods, either on his back or with the help of a trusty mule.[1]: 8 In December, 1861, Francis Jones Barnard established a pony express from Yale to Barkerville. The company had originally been owned by William Jeffray and W.H. Thain and had been known as the Jeffray and Company's Fraser Express. In the summer of 1862, Barnard merged his company into the British Columbia and Victoria Express Company and won the government contract to deliver the mail.[1]: 9 In 1863 Barnard incorporated a two-horse wagon on the run from Lillooet to Fort Alexandria. Another freighting company, Dietz and Nelson operated a stagecoach between Victoria, Lillooet and Yale, connecting with Barnard's Express.[1]: 9 The stages   The BC Express Company had a wide variety of stagecoaches. Some only required two horses and were called a "jerky", while others were pulled by four or six horses. Some had enclosed carriages and others were open. For winter travel, the stagecoaches were replaced by sleighs of all sizes, including some that could carry fifteen passengers. Many of the later stagecoaches were Concord stages, built with shock absorbers made from leather springs which made for a more comfortable ride.[1]: 17 In 1876, the company had a stagecoach built in California specifically for the visit of the Governor General, Lord and Lady Dufferin, who rode in it from Yale to Kamloops and back. The coach was painted in the bright red and yellow BX colours and had the Canadian coat of arms on its front panels. It cost $50 a day to ride in this famous coach, but many visiting diplomats and English aristocracy rode in the Dufferin when they went hunting in the Cariboo.[1]: 19 The horses The first horses used by the company came from Oregon. Then, in 1868, 400 head were purchased in California and Mexico and driven to the company's ranch in Vernon. Later, when the Canadian Pacific Railway was completed, most of the company's horses were bought locally or were shipped from Alberta or Saskatchewan.[1]: 14 The company had a strict policy that they would not purchase any horses that were broken. The company wanted their horses trained exclusively for staging, a process that generally took three months, even then they were never truly broken and had to be expertly handled.[1]: 15, 16 A hostler would lead the teams out to the stages only once the baggage had been secured and the passengers and driver were safely seated. Once harnessed to the stage, the reins were given to the driver and he could release the brake. The stage horses often leaped and reared at the start of a trip, but settled into a smooth trot once they were underway. The whip rarely had to be used to encourage them, as they knew the next station meant a good feed and a warm stable.[1]: 16 The stations were approximately 18 miles apart and the teams were changed at each one. The hostlers at the stations took pride in taking care of the company's horses, often competing to see who kept the teams in the best condition. One rule that was strictly followed was that each horse had its own harness, which was cleaned every time it was taken off. To ensure that the horses always had proper shoes, traveling farriers with portable forges visited the stage stations regularly.[1]: 17 Stage route and fares  After the company's headquarters moved to Ashcroft in 1886, the main stageline extended from Ashcroft to Barkerville, a distance of 280 miles. Other branch lines led to mining camps and settlements all over the Cariboo. The stage fare from Ashcroft to Barkerville was $37.50 in the summer and $42.50 in the winter. Passengers who left the train at Ashcroft and boarded a stage at 4am could expect to arrive at 83 Mile House that evening and Barkerville two days later.[1]: 19 The sternwheeler yearsIn 1903 it was announced that the Grand Trunk Pacific Railway would be coming through from Winnipeg to Prince Rupert via the Yellowhead Pass. In anticipation of the influx of new settlers to the region, Charles Millar expanded the company's services into sternwheelers and automobiles and extended the route to Fort George. The company built an office and steamer landing at the new town of South Fort George in 1910. The sternwheelersThe Royal Mail Ships BX and BC Express were launched in 1910 and 1912 respectively. Both were built by Alexander Watson Jr. at Soda Creek. The BX was built for the route from Soda Creek to Fort George, whereas the BC Express was built for the route from Fort George to Tête Jaune Cache. The captainsThe captain of the BX was Owen Forrester Browne, an experienced Fraser River pilot. By the time he took command of the BX in 1910, he was already well known in the area, as he had been the captain of the local sternwheeler Charlotte. The captain of the BC Express was Joseph Bucey, an experienced Skeena River pilot. On the Skeena, he had piloted the Inlander from Port Essington to Hazelton. Sternwheeler routes and faresThe BX made semi-weekly trips from Soda Creek to Fort George, taking two days for the trip upriver and less than a day for the trip back. In 1910, stage fare from Ashcroft to Soda Creek was $27.50 and the steamer fare from there to Fort George was $17.50. Meals were 75 cents and a berth was $1.50. The stage freight charge was sixty dollars a ton and the steamer freight charge was forty dollars a ton. Automobiles In 1910, the company began running automobiles on the Cariboo Road. A few vehicles, owned by private freighters, had been operating on the road since 1907 and the company realized that they needed to add cars to their services in order to stay competitive.[2]: 168 These vehicles worked on the route from Ashcroft to Soda Creek where they met with the company sternwheelers.[2]: 172 These first cars were Winton Sixes purchased from a car manufacturer in Seattle. The BC Express Company purchased two cars at a cost of $1,500 each and then added a variety of options such as tops at $150, Klaxon horns, $50 and kerosene parking lamps, $75. The Winton Company also provided two drivers, who were also mechanics, as there were few people who knew how to operate and fix a vehicle.[2]: 172 Then the company built a garage and machine shop at Ashcroft and, as there were no service stations, arrangements were also made with Imperial Oil of Vancouver to supply and deliver in drums the gas and oil that the cars would need. The drums were then placed in key locations along the road.[2]: 173 The company purchased more vehicles throughout the next few years and all were painted red and yellow, the company's colours.[2]: 173 Although the freighting business remained brisk and the cars were a favourite with travelers, they never turned a very large profit for the company. Although private operators could discontinue their services when the road conditions were poor, the BC Express Company had advertised automobile services in all weather conditions from May to October. Fulfilling that promise meant that a large crew of mechanics and drivers had to be kept on staff. In 1913, it cost the company $67,233 to maintain their fleet of 8 Wintons. The largest sum went for repairs, but $15,835.53 was spent on tires alone. Furthermore the total profits that were made that season was only $3,337.23, which the company believed was not a large figure considering the risk and investment involved.[2]: 174 The Grand Trunk Pacific Railway At the end of August 1913, Captain Bucey was taking the BC Express up from Fort George to Tête Jaune Cache when he was stopped a cable strung across the river at Mile 141 where the railway was building a bridge.[3] The railway was reneging on their promise not to impede steamer travel on the river. Bucey turned the BC Express back towards Fort George and immediately wired the company's head office at Ashcroft and informed them of the obstruction. The BC Express Company had the Board of Railway Commissioners investigate the situation and the Board came back in the company's favour and told the railway they must build the bridge at Mile 141 (Dome Creek) and the other in the Bear River area (Hansard Bridge) with lift spans as they had promised.[4] The GTP refused the order, stating that if they changed the level of the bridges they'd have to change the level of the grade. The company took the railway to court for damages and loss of revenue, as they had been earning in excess of $5,000 a week on that route, but by the time the case was heard, World War I had begun and the company's attorney was engaged in war work and was unable to appear. His replacement, a junior partner with little experience, was unable to prepare and present the evidence properly and the company lost the case.[5]: 82–83 With no substantive response by the dominion government, the company continued with legal action which was unsuccessfully appealed as far as the Privy Council in London.[6] Some historians have suggested that the railway built the bridges to impede navigation out of spite and dislike for the BC Express Company because its owner at that time, Charles Vance Millar, had successfully negotiated with the First Nations people at Fort George to buy the land that the GTP wanted for their townsite, forcing the GTP to sell some of that prime property to Millar, which he developed and was later called the Millar Addition.[7] The wreck of the BX With the completion of the railway on April 7, 1914 and navigation blocked at the Hansard bridge on the route to Tête Jaune Cache, the company ran the BX and the BC Express only from Soda Creek to Fort George. With the construction of the Pacific Great Eastern Railway underway, the sternwheelers were needed to help deliver equipment and food supplies to the work camps. In 1915, the railway insolvent, work ceased. Despite having a monopoly on river traffic, the BX finished the season with a $7,000 loss.[1]: 92 The BC Express was reserved for special trips. In 1916 and 1917, sternwheelers were not used on the upper Fraser River at all. Then, in 1918, after an appeal from the Quesnel Board of Trade, the provincial government granted the BC Express Company a $10,000 per year subsidy to continue river navigation from Soda Creek to Fort George. The request was justified because Quesnel and the other communities along the river had been promised a railroad, but the construction on the PGE had slowed to a crawl and would in fact not to be completed to Prince George until 1952. In the meantime, the settlers and farmers needed a way to ship their produce to market and steamer fares were the most reasonable option.[1]: 93 [5]: 223 The BX ran until August 30, 1919, when she was punctured by an infamous rock called the "Woodpecker" and sank with a 100 tons of bagged cement intended for construction of the Deep Creek Bridge.[1]: 94 In the spring of 1920, the salvage work was completed and at a cost of $40,000[3]: 58 the BX was raised and patched sufficiently to get her back to Fort George. The BC Express pushed her back upstream through the Fort George Canyon and to the shipyard at Fort George. This would be the first time in the history of sternwheelers that one would push another upriver through a canyon.[5]: 225 The BC Express ran until November 1920 and then it joined the BX on the riverbank at Fort George, where their hulls were abandoned.,[5]: 225 thus ending the days of the pioneer transportation company that Francis Barnard had established nearly 60 years earlier. See also

References and further reading

Notes

External links

|