|

Elizabeth Clarke Wolstenholme-Elmy

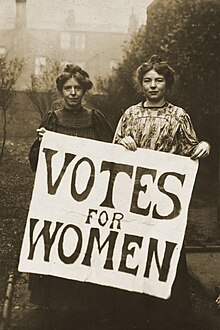

Elizabeth Clarke Wolstenholme-Elmy (née Wolstenholme; 1833 – 12 March 1918) was a British teacher, campaigner and organiser, significant in the history of women's suffrage in the United Kingdom.[1] She wrote essays and some poetry, using the pseudonyms E and Ignota. Early life Elizabeth Clarke Wolstenholme spent most of her life in villages and towns which now form part of Greater Manchester. She was born in Cheetham Hill, Lancashire, the third child and only daughter of Elizabeth (née Clarke), who died shortly after her daughter's birth, and the Rev. Joseph Wolstenholme, a Methodist minister,[2] who died before she was 14. She was baptised on 15 December 1833 in Eccles, Lancashire.[1] Her elder brother, also named Joseph Wolstenholme (1829–1891), was afforded an education, and became a professor of mathematics at Cambridge University,[3] but Elizabeth was not permitted to study beyond two years at Fulneck Moravian School.[1] Despite this limited formal education, she continued learning what she could, and became headmistress of a private girls' boarding school in Boothstown near Worsley. She stayed there until May 1867, when she moved her establishment to Congleton, Cheshire.[1] Early campaigning Wolstenholme, dismayed with the woeful standard of elementary education for girls, joined the College of Preceptors[4] in 1862 and through this organisation met Emily Davies. They campaigned together for girls to be given the same access to higher education as boys. Wolstenholme founded the Manchester Schoolmistresses Association in 1865,[5] and, in 1866, gave evidence to the Taunton Commission, charged with restructuring endowed grammar schools, making her one of the first women to give evidence at a Parliamentary select committee.[1] In 1867, Wolstenholme represented Manchester on the newly formed North of England Council for Promoting the Higher Education of Women. Davies and Wolstenholme quarrelled over how women should be examined at a Higher Level.[6] Wolstenholme, was keen for a curriculum aimed at developing skills for employment, whereas Davies wished for women to be taught the same syllabus as men.[citation needed] Wolstenholme founded the Manchester branch of the Society for Promoting the Employment of Women in 1865,[7] and recruited Lydia Becker to the founding committee.[1] Wolstenholme then began 50 years of vigorous campaigning for women's suffrage — the right to vote. She gave up her school in 1871 and became the first paid employee of the women's movement when she was employed to lobby Parliament with regard to laws that were injurious to women.[8] Nicknamed 'the Scourge of the Commons' or the 'Government Watchdog',[9] Wolstenholme took her role seriously. When local women's suffragist groups faltered following the disappointment of failed suffrage bills, Wolstenholme was instrumental in maintaining the momentum of her city's committee with a re-grouping in 1867 under the name Manchester Society for Women's Suffrage.[citation needed] In 1877, the women's suffrage campaign was centralised as the National Society for Women's Suffrage. Wolstenholme was a founding member (with Harriet McIlquham and Alice Cliff Scatcherd) of the Women's Franchise League in 1889.[10][11] Wolstenholme left the organisation and founded the Women's Emancipation Union in 1891.[12] Women's Emancipation Union 1891–1899Wolstenholme founded the Women's Emancipation Union in September 1891 following an infamous court case. Regina v Jackson, known colloquially as the Clitheroe Decision,[13] occurred when Edmund Jackson abducted his wife in a bid to enforce his conjugal rights, long before the concept of marital rape existed. The court of appeal freed Mrs Jackson under Habeas corpus.[14] Wolstenholme recognised the significance of this judgement in relation to coverture, the principle that a wife's legal personhood was subsumed in that of her husband.[1] She described the "epoch making" outcome as "the greatest victory the woman's cause has ever yet gained, greater even than the passing of the Married Women's Property Acts"[15][page needed] and as a watershed moment in improving the laws governing marriage.[16] Wolstenholme funded the WEU by subscriptions and by finding a benefactor, Mrs Russell Carpenter.[17] The WEU campaigned for four great equalities between men and women: in civic rights and duties, in education and self-development, in the workplace, and in marriage and parenthood. It pioneered cross-class collaborations, encouraging women's resistance to authority while their right to vote remained unacknowledged. It also advocated making women's suffrage a test question in the selection of prospective parliamentary candidates.[18] The WEU committee held an annual conference and over 150 public meetings between 1892 and 1896. Papers given at the conferences included Amy Hurlston's "The Factory work of Women in the Midlands"[19] and William Henry Wilkins's "The Bitter Cry of the Voteless Toiler",[20] both in 1893, and Isabella Bream Pearce's "Women and Factory Legislation" in 1896.[citation needed] There were ten local organisers in cities from Glasgow to Bristol, and international subscriptions of over 7,000. A short-lived Parliamentary subcommittee was established in 1893. Executive members included Mona Caird, Harriot Stanton Blatch, Caroline Holyoake Smith, and Charles W. Bream Pearce (husband of Isabella Bream Pearce). Members included Lady Florence Dixie, Charlotte Carmichael Stopes, and George Jacob Holyoake. Isabella Ford worked on behalf of the WEU at outdoor rallies in London's East End in 1895.[18] Following the Local Government Act 1894, the WEU worked to encourage those women who were covered by it (mostly property owners) to stand for election in bodies of local administration, or at least to vote. Over 100 of the WEU organisers were elected as Poor Law Guardians or Parish Councillors.[1] Following the death of their benefactor and a halving of their subscriptions in the slump following the loss of the 1897 Women's Suffrage Bill, the WEU folded. The final meeting was held in 1899, when the speakers included Harriot Stanton Blatch and Charlotte Perkins Gilman.[18] WSPU Wolstenholme, a long-time friend and colleague of Emmeline Pankhurst,[21] was invited to became a member of the executive committee of the Women's Social and Political Union.[22] The WEU was a forerunner to the combative 'militant' WSPU suffragettes.[18]  Wolstenholme was on the stage when Keir Hardie and Pankhurst spoke to a large crowd in Trafalgar Square, and also wrote an eyewitness account of the 1906 Boggart Hole Clough meeting and the 1908 Women's Sunday,[1] where she was honoured with her own stand. In the 1911 Coronation Procession, watching from a balcony, she was dubbed 'England's oldest' suffragette ('militant suffragist'). Wolstenholme resigned from the WSPU in 1913, when its activities became more militant and potentially threatened human life, as she supported pacifism and the doctrines of non‐violence throughout her life.[9]  Further activitiesShe became vice-president of the Women's Tax Resistance League in the same year. She also gave her support to the Lancashire and Cheshire Textile and other Workers' Representation Committee, formed in Manchester during 1903 headed by Esther Roper.[23] Wolstenholme was not a single issue campaigner and wanted parity between the sexes. She became secretary to the Married Women's Property Committee from 1867 until its success with the introduction of the Married Women's Property Act 1882.[24] In 1869, she invited Josephine Butler to be president of the Ladies National Association for the Repeal of the Contagious Diseases Acts, a campaign which succeeded in 1886. Until 1874, Wolstenholme worked as secretary of the Vigilance Association for the Defence of Personal Rights, later the Personal Rights Association.[9] In 1883, Wolstenholme worked for the Guardianship of Infants Committee that became an act in 1886 (see Custody of Infants Act 1873).[25] Personal lifeWolstenholme met silk mill owner, secularist, republican (anti-monarchist), and women's rights supporter Benjamin John Elmy (1838–1906) when she moved to Congleton, Cheshire. He became her soulmate and domestic partner in a free union. Elmy was born in Hollingsworth to Benjamin Elmy, an Inland Revenue officer, and Jane (née Ellis) Elmy.[26] Working as a teacher in his early 20s, Elmy lost his faith and became a factory manager in Lancashire's textile trade. It was this work that gave him insights into economic hardships that beset women workers.[26] In 1867, Wolstenholme and Elmy set up a Ladies' Education Society that was open to men. He became active in the women's movement, joining Wolstenholme's committees. The couple began living together in the early 1870s,[27] following the free love movement and horrifying their devout Christian colleagues. When Wolstenholme became pregnant in 1874, her colleagues were outraged and demanded that they marry, against their personal beliefs.[28] Despite the couple going through a civil marriage registry ceremony on 12 October 1874,[28] she was forced to give up her job in London.[citation needed] The couple moved to 23 Buxton Road, Buglawton, where Wolstenholme-Elmy gave birth to their son, Frank, in 1875. Frank was educated at home. In 1886, Benjamin J. Elmy was elected as Master of the Congleton Lodge of the Fair Trade League (supporting protection of British industry) and both Wolstenholme and Elmy were popular speakers at events organised against the free trade laws. Elmy and Co. ceased trading in 1888 and Elmy retired due to ill health in 1891.[18] In 1897, he founded the first Male Electors League for Female Suffrage (see also the 1907 Men's League for Women's Suffrage). The couple remained married until Elmy's death in 1906. Later years and deathIn her later years, Wolstenholme found travelling from her home to London physically difficult, and public life became limited to writing letters to the press in support of the causes she championed.[1] Wolstenholme's friend Emmeline Pankhurst described her in later life as: "a tiny Jenny-wren of a woman, with bright, bird-like eyes, and a little face, child-like in its merriment and its pathos, which even in extreme old age retained the winning graces of youth and unbound hair falling in ringlets on her shoulders, which all! her life she wore thus in the fashion of her girlhood".[29] Wolstenholme died in her home at Chorlton-on-Medlock on 12 March 1918, shortly after women were granted the vote.[1] Her funeral was held at the Manchester Crematorium.[citation needed] Works Wolstenholme wrote prolifically, including papers for the National Association for the Promotion of Social Science and articles for feminist publications such as Shafts and national newspapers such as the Westminster Review. Pamphlets concerning her campaigns were also published by organisations like the Women's Emancipation Union.[30] Her writing includes:

The British Library holds her papers and those of the Guardianship of Infants Act and the Women's Emancipation Union.[30] Wolstenholme also wrote poetry. 'The Song of the Insurgent Women' was published on 14 November 1906 and (as Ignota) 'War Against War in South Africa' on 29 December 1899, shortly after the start of the Second Boer War.[30] Posthumous recognition  A blue plaque was installed at her home, Buxton House, by the Congleton Civic Society. It reads Elizabeth Wolstenholme-Elmy 1839–1918 Campaigner for social, legal and political equality for women lived here 1874–1918 (citing "1839" as Wolstenholme-Elmy's year of birth, but other sources cite 1833). Her name and image, and those of 58 other women's suffrage supporters, are etched on the plinth of the statue of Millicent Fawcett in Parliament Square, London, which was unveiled in 2018.[31]  In April 2021, a new Congleton linkroad was named Wolstenholme Elmy Way in honour of Elizabeth and her husband, Benjamin.[32] A charity[33] was set up in Congleton in 2019 to raise her profile. Elizabeth's Group raised funds to create a statue in Wolstenhome's memory.[34] It was designed by sculptor Hazel Reeves and unveiled by Baroness Hale of Richmond on International Women's Day, 8 March 2022.[35][36] ReferencesNotes

Bibliography

External links |

||||||||||||||||||||