|

Ester Boserup

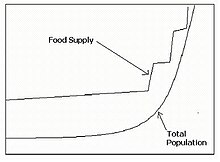

Ester Boserup (18 May 1910[1] – 24 September 1999) was a Danish economist. She studied economic and agricultural development, worked at the United Nations as well as other international organizations, and wrote seminal books on agrarian change and the role of women in development. Boserup is known for her theory of agricultural intensification, also known as Boserup's theory, which posits that population change drives the intensity of agricultural production. Her position countered the Malthusian theory that agricultural methods determine population via limits on food supply. Her best-known book on this subject, The Conditions of Agricultural Growth, presents a "dynamic analysis embracing all types of primitive agriculture." (Boserup, E. 1965. p 13)[2] A major point of her book is that "necessity is the mother of invention". Her other major work, Woman's Role in Economic Development, explored the allocation of tasks between men and women, and inaugurated decades of subsequent work connecting issues of gender to those of economic development, pointing out that many economic burdens fell disproportionately on women.[3] In an early review, her book was called "pioneering;" nearly five decades later, it has proved influential, having been cited by thousands of other works.[4] It was her great belief that humanity would always find a way and was quoted in saying "The power of ingenuity would always outmatch that of demand". She also influenced the debate on women in the workforce and human development, and the possibility of better opportunities of work and education for women. Her work earned her three honorary doctorate degrees: one from Wageningen University; one from Brown University; and one from the University of Copenhagen. She was also elected to the US National Academy of Sciences as a Foreign Associate in 1989.[5] The doctorates were in three different fields: agricultural, economic, and human sciences, respectively; the interdisciplinary nature of her work is reflected in these honors, just as it distinguished her career.[6] Of interdisciplinarity, Boserup said: "Somebody should have the courage not to specialise and to look at how one can bring things together. That is what I have tried to do."[5] BiographyHer father was a Danish engineer, who died when she was 2 years old. The family was almost destitute for several years. Then, "encouraged by her mother and aware of her limited prospects without a good degree,"[7] she studied economic and agricultural development at the University of Copenhagen from 1929, and obtained her degree in theoretical economics in 1935. Ester had married Mogens Boserup when both were twenty-one; the young couple lived on his allowance from his well-off family during their remaining university years.[7] Their daughter, Birte, was born in 1937; their sons Anders, in 1940, and Ivan, in 1944. After graduation Boserup worked for the Danish government from 1935–1947, right through the Nazi occupation in WWII. As head of its planning office, she worked on studies involving the effects of subsidies on trade. She made almost no reference to conflicts between family and work during her lifetime. The family moved to Geneva in 1947 to work with the UN Economic Commission of Europe (ECE). In 1957, she and Mogens worked in India in a research project run by Gunnar Myrdal; she and Mogens worked in India until 1960. For the rest of her life, she worked as a consultant and writer. She and Mogens lived in Senegal for a year between 1964 and 1965, while he was leading the UN's effort to help establish the African Institute for Economic Development and Planning.[7][8] She was based in Copenhagen until her husband died in 1980, after which she settled near Geneva. In her later years, in the 1990s, she lived in Ticino, Switzerland.[5] WorkScholarly contributionsHer first major work, The Conditions of Agricultural Growth: The Economics of Agrarian Change Under Population Pressure, laid out her thesis, informed by her experience in India in opposition to many views of the time.[6] According to Malthusian theory, the size and growth of the population depend on the food supply and agricultural methods. In Boserup's theory, agricultural methods depend on the size of the population. In the Malthusian view, when food is not sufficient for everyone, the excess population will die. However, Boserup argued that in those times of pressure, people will find ways to increase the production of food by increasing workforce, machinery, fertilizers, etc.  Although Boserup is widely regarded as being anti-Malthusian, both her insights and those of Malthus can be comfortably combined within the same general theoretical framework.[9] Boserup argued that when population density is low enough to allow it, land tends to be used intermittently, with heavy reliance on fire to clear fields, and fallowing to restore fertility (often called slash and burn farming). Numerous studies have shown such methods to be favorable in total workload and also efficiency (output versus input). In Boserup's theory, it is only when rising population density curtails the use of fallowing (and therefore the use of fire) that fields are moved towards annual cultivation. Contending with insufficiently fallowed and less fertile plots, covered with grass or bushes rather than the forest, mandates expanded efforts at fertilizing, field preparation, weed control, and irrigation. These changes often induce agricultural innovation, but increase marginal labor cost to the farmer as well. The higher the rural population density, the more hours the farmer must work for the same amount of produce. Therefore, workloads tend to rise while efficiency drops. This process of raising production at the cost of more work at lower efficiency is what Boserup describes as "agricultural intensification". Boserupian TheoryAlthough Boserup's original theory was highly simplified and generalized, it proved instrumental in understanding agricultural patterns in developing countries.[10] By 1978, her theory of agricultural change began to be reframed as a more generalized theory.[11] The field continued to mature in to relation to population and environmental studies in developing countries.[12] Neo-Boserupian theory continues to generate controversy with regards to population density and sustainable agriculture.[13] Originally published in 1965, The Conditions of Agricultural Growth has been republished at least 16 times afterward and has been translated into at least four additional languages.[6] Gender studiesBoserup also contributed to the discourse surrounding gender and development practices with her 1970 work Woman's Role in Economic Development.[14] The work is "the first investigation ever undertaken into what happens to women in the process of economic and social growth throughout the Third World". Boserup's work is widely credited as a motivation behind the United Nations Decade for Women.[6] In addition, according to the foreword in the 1989 edition by Swasti Mitter, "It is [Boserup's] committed and scholarly work that inspired the UN Decade for Women between 1975 and 1985, and that has encouraged aid agencies to question the assumption of gender neutrality in the costs as well as in the benefits of development". Boserup's text evaluated how work was divided between men and women, the types of jobs that constituted productive work, and the type of education women needed to enhance development. This text marked a shift in the Women in Development (WID) debates because it argued that women's contributions, both domestic and in the paid workforce, contributed to national economies. Many liberal feminists took Boserup's analysis further to argue that the costs of modern economic development were shouldered by women.[3] Woman's Role in Economic Development, too, has been republished many times, appearing in print in at least a half dozen languages.[6] Selected bibliography

Books

Chapters in books

Journal articles

References

Further reading

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||