|

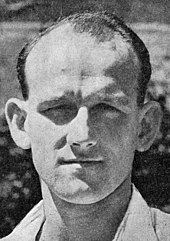

Frank Tyson

Frank Holmes Tyson (6 June 1930 – 27 September 2015) was an England international cricketer of the 1950s, who also worked as a schoolmaster, journalist, cricket coach and cricket commentator after emigrating to Australia in 1960. Nicknamed "Typhoon Tyson" by the press, he was regarded by many commentators as one of the fastest bowlers ever seen in cricket[1][2][3][4] and took 76 wickets at an average of 18.56 in 17 Test matches. In 2007, a panel of judges declared Tyson Wisden Leading Cricketer in the World for 1955 due to his outstanding tour of Australia in 1954–55 where his 28 wickets (20.82) was instrumental in retaining the Ashes. Tyson coached Victoria to two Sheffield Shield victories and later coached the Sri Lankan national cricket team.[5] He was a cricket commentator for 26 years on ABC and Channel Nine. Early lifeTyson's mother was Violet Tyson (born 1892) and his father worked for the Yorkshire Dyeing Company, but died before his son was selected for England.[6] As a boy he played cricket with his elder brother David Tyson, who served in Australia during the war; at school he practised his run-up on the balcony. He was educated at Queen Elizabeth's Grammar School, Middleton, and studied English literature at Hatfield College, Durham University As a university graduate, Tyson was unusual among professional cricketers in the 1950s. He was a qualified schoolmaster and used to read the works of Geoffrey Chaucer, George Bernard Shaw and Virginia Woolf on tour.[7] Instead of sledging batsmen he quoted Wordsworth: "For still, the more he works, the more/Do his weak ankles swell".[8] He completed his National Service in the Royal Corps of Signals in 1952 as a Keyboard Operator and Cypher. Sportsmen were generally retained on headquarters staff and he played cricket for his platoon, squadron, regiment, area command and the Army.[9] He served at the Headquarters Squadron 4 Training Regiment where he controlled the movements of men transferring in and out of Catterick, but not very well. He abhorred guns and when he took his rifle training he made sure that he always missed the target. In 1952–53 he worked felling trees, which John Snow regarded as an excellent exercise for developing the muscles of a fast bowler and attended Alf Gover's East Hill Indoor School for cricketers. In 1954–55 Gover covered the Ashes tour as a journalist and advised Tyson to use the shorter run-up from his league cricket days, which proved to be a turning point in the series.[10] Early cricket career 1952–54Before he became a professional cricketer Tyson played for Middleton in the Central Lancashire League, Knypersley in the North Staffordshire League, Durham University and the Army. Although invited for trials by Lancashire at Old Trafford he was turned down 'because he dipped at the knee',[11] so he qualified for Northamptonshire in 1952 through residence. Tyson made his first-class debut against the Indian tourists in 1952, after his first ball the slips moved back an extra five yards and his first wicket was that of the Test batsman Pankaj Roy for a duck.[12] Tyson's second first-class match was against the Australians in 1953. Richie Benaud was told that the unknown Tyson was a bowler fresh out of Durham University who would give them no trouble. They began to revise this estimation when they saw the wicket-keeper take position halfway to the boundary and young Tyson walked over to the sightscreen to begin his run up. The first ball ricocheted off the edge of Colin McDonald's bat to the boundary, the second trapped him lbw before he could play a stroke, the third was a bouncer that flew past Graeme Hole's nose and the fourth was a yorker that clean bowled Hole and sent his stumps cartwheeling over the wicket-keeper's head.[13] In 1954 at Old Trafford Tyson hit the sightscreen with the ball after it bounced once on the pitch. He is one of only four bowlers to have achieved this feat in the history of the game, the others being Charles Kortright, Roy Gilchrist and Jeff Thomson.[14] and he was given his county cap in the same year, his first full first-class season. Tyson reckoned that he received his Test call up when ex-England captains Gubby Allen and Norman Yardley saw him hospitalise Bill Edrich at Lords. Edrich, a noted hooker of fast bowling, mistimed his stroke due to the speed of the ball and his cheek bone was broken. The Marylebone Cricket Club (MCC) were thereby convinced of the speed and hostility of Tyson's bowling and decided to take him to Australia.[15] He was selected to play for England against Pakistan at the Oval in 1954, taking 4–35 and 1–22 and making 3 runs in each innings batting at number eight, but Pakistan won the match by 24 runs thanks to the bowling of Fazal Mahmood. Although he batted at number eleven in league cricket "The Middleton groundsman was a fatalist. He used to start up the roller to refurbish the wicket when I went in to bat".[16] Tyson worked on his batting and in 1954 "was building up a reputation as an all-rounder, scoring consistently with the bat",[17] and he batted at number seven for England. However, this did not develop as much as expected and he reverted to being a lower-order batsman. Tour of Australia and New Zealand 1954–55First Test vs Australia at BrisbaneTyson was chosen for the MCC tour of Australia in 1954–55, seen as a replacement for Fred Trueman who was controversially left behind. Freed of rationing Tyson increased his weight from 161 lb (73 kg) to 182 lb (83 kg) within a month of leaving the UK.[18] Hutton won the toss, put Australia in to bat and watched England drop 14 catches as Australia made 601/8 declared. Tyson was hit for 1/160 off 29 eight ball overs and England lost by an innings and 154 runs. Even so, Tyson hit Arthur Morris and Neil Harvey repeatedly with the ball and they were badly bruised. More to the point he bounced Ray Lindwall after the Australian all-rounder knocked several boundaries off the fast bowler on his way to 64 not out. Tyson also managed to run out Graeme Hole and made 37 not out in the second innings, which remained his highest Test score. Second Test vs Australia at SydneyTaking advice from his old coach Alf Gover, who was in Australia as a journalist, Tyson stopped using his laborious 38-yard run up and returned to a shorter run up used in league cricket with ten short then ten long final strides.[10][12][19] With this he took 4/45 in the first innings, described vividly by Margaret Hughes: "Harvey received a beast of a ball from Tyson which spat up at him and splashed off his bat to Cowdrey".[20] Ray Lindwall had bowled Tyson for a duck in the England first innings and was bounced again, so in the second innings the Australian fast bowler took his revenge:

Players did not wear protective helmets in the 1950s and he had to be helped off the field with a large bump on his head that was visible from the stands. He was taken to hospital for x-rays, but returned to loud applause only to be bowled by Lindwall for 9. The Australians needed 223 to win, but were afraid that Tyson would send down a barrage of fast, short-pitched bowling, but he was intelligent enough to bowl full-length deliveries that caught them unprepared.[22] While Brian Statham bowled "up the cellar steps"[23] and into the wind Tyson tore down the slope from the Randwick End with "half a gale"[24] behind him and bowled "as fast as man has ever bowled".[25] He took 6/85 in the innings and 10/130 in the match to give England a 38 run victory. The Australian captain Arthur Morris told the newspapers "Such fine bowling deserved to win".[26] Peter Loader told Tyson, "you bowled like a 'Dingbat'" and the nickname 'Dingers' stuck".[27] Third Test vs Australia at MelbourneThe Third Test cemented the "Typhoon" reputation. He took 2/68 in the first innings and at the end of the fourth day Australia needed 240 to win and were 75–2, with Tyson on 1/11. Over 50,000 Australian fans came on the fifth day to see Neil Harvey and Richie Benaud knock off the remaining 165 runs, but what they got was 'the fastest and most frightening sustained spell of fast bowling seen in Australia'.[28] as Tyson took 6/16 off 6.3 overs from the Richmond End. His 7/27 in the innings was his best Test innings analysis, the best by an England bowler in Australia since Wilfred Rhodes took 8/68 in 1903–04 and has not been bettered since. Australia added only 36 runs, were dismissed for 111 and England won by 128 runs. The game finished well before lunch and the caterers were left with thousands of unsold pies when the crowd deserted the ground. Fourth Test vs Australia at AdelaideThe Ashes were decided at Adelaide, Hutton cunningly changing his bowlers to mix the pace of Tyson and Brian Statham with the spin of Bob Appleyard and Johnny Wardle. Tyson took 3/85 and 3/47 as Australia fell for 111 in the second innings to lose the Test by five wickets and the series 3–1. It was the first time England had won a series in Australia since 1932–33, they would not win another until 1970–71. Fifth Test vs Australia at SydneyDespite three days lost to rain, an aggressive England team almost made it 4–1. Tyson took 2/45 and 0/20 as Australia followed on, needing 32 runs to make England bat again with only four wickets left. Tyson had taken 28 wickets in the series at 20.82 and was named one of the five Wisden Cricketers of the Year in 1956. Stokes McGown, a Botany Bay Sports Goods manufacturer made autographed cricket balls in his honour; ironically 'The Typhoon' ball was good for swinging, unlike its namesake.[29] First Test vs New Zealand at DunedinAfter Australia, England toured New Zealand, who had yet to win a Test match. Tyson took 3/23 and 4/16 in the First Test as New Zealand were dismissed for 125 and 132 and England won by 8 wickets despite making only 209/8 declared in their first innings. Second Test vs New Zealand at AucklandIn this extraordinary Test Tyson took 2/41 in the New Zealand first innings of 200. When he joined Len Hutton on 164/7 the home side looked like getting a first innings lead and one gentleman even booked a flight to Auckland in the hope of seeing New Zealand's first Test victory.[30] Hutton told Tyson to "Stick around for a while Frank, we may not have to bat again",[21] a prediction that Tyson later thought verged on second sight. He did hang round a bit and made 27 not out in England's 246. New Zealand spectacularly collapsed and were out for 26 to lose by an innings and 20 runs, the lowest completed score in Test cricket, Tyson taking 2/10 in the debacle. Later cricket career 1955–1959See main articles English cricket team in Australia in 1958–59 and 1958–59 Ashes series Tyson returned to England a hero, but Northants refused to pay for a civic welcome, though the Supporters Club arranged a Welcome Home function at the Northampton Repertory Theatre.[31] Northamptonshire was an unfancied county known for its "cabbage patch" home wickets which reduced the effectiveness of Tyson's bowling and would shorten his career. Management ignored his pleas for a faster wicket because of their spin bowlers George Tribe, Jack Manning and Micky Allen.[31] Len Hutton advised him to move back to Lancashire to team up with Brian Statham, but county transfers were difficult in those days and Tyson stayed at Northants. In the Test arena he demonstrated the pace that had overpowered the Australians on a green wicket at Trent Bridge, taking 2/51 and 6/28 against South Africa as they fell to an innings defeat. In his first nine tests he had taken 52 wickets at 15.56, but this was effectively the end of his career as England's premier fast bowler. A badly blistered right heel forced him to miss the Second Test at Lord's and this injury would dog him for the remainder of his career. It was thought at the time that this was due to his violent pounding his foot received when he delivered the ball, but it was later found to be caused by the friction of his heel turning in ill-fitting boots.[21] His place was taken by his Yorkshire rival Fred Trueman and Tyson's last eight Tests were played intermittently over a period of four years before he retired. He returned to play in the Third Test vs South Africa at Old Trafford taking 3/124 and 3/55, but missed the last two Tests. A series of injuries kept him out of the England team and he did not play until the Fifth Test against Australia at The Oval in 1956, when he took 1/34 in the first innings and did not bowl in the second. In South Africa in 1956–57 he barely bowled in the First Test at Johannesburg and was only recalled for the Fifth Test at Port Elizabeth, where he took 2/38 and 6/40 bowling off a five-yard run up.[32] In 1957 he took his best first-class bowling; 8/60 against Surrey at the Kennington Oval with 5/52 in the second innings to return 13/112, his best match figures. Wisden reported '...nearly half the runs scored off him came from the edge'.[33] Tyson toured Australia again in 1958–59, but the pitches were slower than four years before and the injury-struck Tyson only played in the Fourth and Fifth Tests, taking three wickets at 64.33. His last hurrah was in New Zealand, where he took 3–23 and 2–23 in the First Test at Christchurch and 1/50 in a rain affected draw in the Second Test at Auckland, taking a wicket with his last ball in Test cricket. He toured South Africa with the Commonwealth XI in 1959–60, taking 1/80 and 4/53 against Transvaal. Style

In League, university and Army cricket Tyson had used a 'short' run up of 18 or 20 yards consisting of ten short steps and ten long final strides to the wicket.[34] When he moved to first-class cricket this increased to 38 yards, starting near the sightscreen and over 200 feet from the wicket-keeper, who was often reduced to an athletic long stop.[12][19] With a final leap to the wicket he released the ball with a high arm action and a heave of his shoulders, 'the ferocity of his delivery' was described as 'every muscle is in use, the right foot takes the strain, the right arm is straight ready for delivery and the left leg kicks out menacingly'.[28] Australian newspapers had accused Tyson of dragging his right foot over the popping crease on the 1954–55 tour and an English newspaper responded; "Will Tyson be "sacrificed" to avoid any risk of giving the Australians a chance to scream that Tyson persistently bowls no-balls by foot-drag over the crease?" with pictures of his bowling action.[35] In the match between the Victoria and the M.C.C. he was photographed dragging his foot 18 inches past the crease, but Pat Crawford of New South Wales was photographed with his foot 36 inches over the crease. The caption reading "Oh Tyson. You are an Angel compared to Pat!"[36] An enterprising Sydney newspaper paid Harold Larwood to give his name to an article declaring "Replay Tests – Tyson Not Fair".[36] Unlike the great swing bowler Fred Trueman he 'bowled straight and...never intentionally bowled an out-swinger.[37] Instead Tyson relied on his tremendous pace to take most of his wickets, batsmen were often caught in mid-stroke by the speed of the ball coming onto the bat, or were too nervous to play fluently.[10] On a green or crumbling wicket providing movement he could simply blast his way through the batting, and produced bounce and pace even off the placid Northamptonshire wickets. Tyson believed that a bouncer should 'pin the batsman against the sightscreen' and frequently used them to intimidate batsmen, even tailenders.[10] His ungainly action and quest for raw speed took a toll on even his strong body and he suffered from a series of injuries which brought a premature end to his career. In 1994 he had operations to his right arm and knees and a further operation on his knees in 2001 rendered him practically immobile for a short time.[38] In his autobiography A Typhoon Called Tyson he wrote:

He was no simple bowler, but thought hard how to dismiss and deceive batsman. John Arlott wrote "This was intelligence, rhythm and strength merged into the violent craft of fast bowling" and "He is intelligent beyond the usual run of fast bowlers: he is the type of cricketer whom improves rapidly through thinking about the game".[40] Typhoon Tyson

His fast bowling gave him the nickname "Typhoon Tyson", and despite his short career he achieved status as the fastest England bowler in living memory. Don Bradman called him "the fastest bowler I have ever seen"[2] and Richie Benaud agreed, writing "For a short time, Frank Tyson blasted all-comers".[3] Tom Graveney wrote 'I cannot believe any bowler was faster than Tyson at that time'.[12] When fielding in the slips he had 'to stand 40 yards off the bat, and still. the ball was often going over our heads from edged shots'.[42] His Northants colleague Jock Livingston said 'When really firing, Tyson was the quickest of all over a period of three or four overs'.[12] Livingston had seen Harold Larwood bowl Bodyline and batted against the Australian fast bowlers Miller and Lindwall in the Sheffield Shield. At the Aeronautical College in Wellington, New Zealand in 1955 metal plates were attached to a cricket ball and a sonic device was used to measure their speed, with Tyson's bowling measured at 89 mph (143 km/h), but he was wearing three sweaters on a cold, damp morning and used no run up, Brian Statham bowled at 87 mph (140 km/h).[10] He certainly bowled faster than 89 mph in matches, and Tyson claimed that he could bowl at 119 mph (192 km/h), but this cannot be proven.[38][43] The best that can be said was that he was noticeably faster than his contemporaries Ray Lindwall, Keith Miller, Fred Trueman, Brian Statham, Peter Heine and Neil Adcock. His great fast bowling rival Fred Trueman 'was forever being told that when it came to bowling I was very fast, but on his day Frank Tyson was faster than me'[44] and it was Tyson who kept Trueman out of the England team in 1954–55. When they played together in a Gentlemen v Players match at Scarborough in 1957 the captain Godfrey Evans insisted Trueman bowl into the headwind so as to give the faster Tyson the advantage of the tailwind.[45] Dickie Bird, the famous England umpire, wrote "he was certainly the quickest bowler I ever seen through the air, and on one occasion the quickest bowler I never saw through the air".[46] When playing for Yorkshire vs the MCC at Scarborough in 1958 "I opened the innings against him and hit his first three deliveries through the off side for four. With supreme confidence I went on to the front foot for the fourth ball. Tyson dropped one short. It reared up and hit me on the chin. I went down as if I'd just been on the receiving end of a right hook...I still carry the scar to show my folly that day. There was blood all over and I saw stars. I could hear bells ringing in my head...".[47] Dickie came back to score his then-highest first-class score of 62 and Tyson took 4/30. When they met in Australia in 1998–99 Tyson joked 'You're looking well Dickie. See you still have the scars though'.[46] Later careerFrank Tyson met his wife Ursula Miels (born in 1936) in Melbourne on the 1954–55 tour, and they married in a Melbourne church on 22 November 1957 with much publicity. They had three children, Philip (a non-Typhoon medium-paced bowler), Sara and Anna, and eight grandchildren.[48] He retired from first-class cricket in 1960 and emigrated to Australia as a ten-pound pom, as his hero Harold Larwood had done ten years earlier. "It had struck me while I was over there that it was a wonderful country to bring up a family, with the open spaces, the climate and the job opportunities".[49] He became a schoolmaster at Carey Baptist Grammar School in Melbourne, teaching English, French and History, later becoming a housemaster and the head of languages.[49] Tyson worked as a cricket coach in Melbourne and was the captain-coach of University of Melbourne Cricket Club.[50] He also played for Todmorden Cricket Club in the Lancashire League in 1961, the Prime Ministers XI in 1963–64, International Cavaliers in 1968, Old England vs Old Australia in 1980 and Footscray Cricket Club. He was recruited as the Director of Coaching for the Victorian Cricket Association, taking them to two Sheffield Shield victories, and helped establish the Australian National Accreditation Scheme in 1974. From 1990 to 2008 he travelled to India to teach the coaches at the National Cricket Academy[51] and Mumbai Cricket Association[52] and coached the Sri Lankan national cricket team for the World Cup.[5] On the 1954–55 tour he had written columns for the Empire News and Manchester Evening News, and when he retired he wrote for the Observer, the Daily Telegraph and the Melbourne Age, and contributed to The Cricketer International magazine.[10] He was also a cricket commentator on ABC television for 26 years, and for Channel Nine from 1979 to 1986, forming a partnership with Tony Greig. Following his full retirement, Tyson enjoyed his house on the Gold Coast, where he could "wake up every day in the sun". He went to the gym three times a week, enjoyed swimming, and spent his time making oil paintings of cricketers and cricket grounds.[53] Books written by Frank Tyson

Light entertainmentCalypsoThe calypso singer Lord Kitchener released a single, "The Ashes (Australia vs MCC 1955)", lauding Tyson's contributions to England's victory. Hancock's Half HourOn 4 March 1956 Tyson appeared on Programme 20 of the third series of the radio version of Hancock's Half Hour, "The Test Match", with Tony Hancock and Sidney James, with guests cricket commentator John Arlott and his England teammates Godfrey Evans and Colin Cowdrey. Notes

References

External links |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||