|

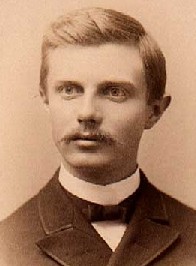

Frederick Jackson Turner

Frederick Jackson Turner (November 14, 1861 – March 14, 1932) was an American historian during the early 20th century, based at the University of Wisconsin-Madison until 1910, and then Harvard University. He was known primarily for his frontier thesis. He trained many PhDs who went on to become well-known historians. He promoted interdisciplinary and quantitative methods, often with an emphasis on the Midwestern United States. Turner's essay "The Significance of the Frontier in American History" included ideas that formed the frontier thesis. In it, Turner argued that the moving western frontier exerted a strong influence on American democracy and the American character from the colonial era until 1890. He is also known for his theories of geographical sectionalism. During recent years historians and academics have argued frequently over Turner's work; however, all agree that the frontier thesis has had an enormous effect on historical scholarship. Early life and educationBorn in Portage, Wisconsin, the son of Andrew Jackson Turner and Mary Olivia Hanford Turner, Turner grew up in a middle-class family. His father was active in Republican politics, an investor in a railroad, and was a newspaper editor and publisher.[1] His mother taught school.[2] Turner was very much influenced by the writing of Ralph Waldo Emerson, a poet known for his emphasis on nature; so too was Turner influenced by scientists such as Charles Darwin, Herbert Spencer, and Julian Huxley, and the development of cartography.[3] In 1884, he graduated from the University of Wisconsin, which was later renamed the University of Wisconsin–Madison.[1] While there, Turner was a member of the Phi Kappa Psi Fraternity. He earned his PhD in history from Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore in 1890 with a thesis on the fur trade in Wisconsin, titled The Character and Influence of the Indian Trade in Wisconsin,[4] under the academic supervision of Herbert Baxter Adams. CareerTurner did not publish extensively; his influence came from tersely expressed interpretive theories in his articles, which influenced his hundreds of disciples. Two theories, in particular, were influential, the "Frontier Thesis" and the "Sectional Hypothesis". Although he published little, he had an encyclopedic knowledge of American history, earning a reputation by 1910 as one of the two or three most influential historians in the country. He proved adept at promoting his ideas and his students, for whom he obtained jobs in major universities, including Merle Curti and Marcus Lee Hansen. He circulated copies of his essays and lectures to important scholars and literary people, published extensively in magazines, recycled favorite material, attaining the largest possible audience for major concepts,[5] and wielded considerable influence within the American Historical Association as an officer and advisor for The American Historical Review. His emphasis on the importance of the frontier in shaping American character influenced the interpretation found in thousands of scholarly histories. By the time Turner died in 1932, 60% of the major history departments in the U.S. were teaching courses in frontier history compatible with Turner's theories.[6] Annoyed by the university regents who demanded less research and more teaching and state service, Turner sought an environment that would permit him to do more research.[7] Declining offers from the University of California, he accepted an offer from Harvard University in 1910 and remained a professor there until 1922,[1] being succeeded in 1924 by Arthur M. Schlesinger, Sr. In 1907 Turner was elected a member of the American Antiquarian Society,[8] and in 1911 he was elected a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.[9] Turner was never comfortable at Harvard; when he retired in 1922 he became a visiting scholar at the Huntington Library in Los Angeles, where his note cards and files continued to accumulate, although few monographs got published. His The Frontier in American History (1920) was a collection of older essays. As a professor of history at the University of Wisconsin from 1890 to 1910 and Harvard from 1910 to 1922, Turner trained scores of disciples who, in turn, dominated American history programs throughout the country. His model of sectionalism as a composite of social forces, such as ethnicity and land ownership, encouraged historians to use social history to analyze social, economic and political developments of American history. At the American Historical Association, he collaborated with J. Franklin Jameson on numerous major projects.[10] Turner's theories became unfashionable during the 1960s, as critics complained that he neglected regionalism. They complained that he claimed too much egalitarianism and democracy for a frontier that was restrictive for women and minorities. After Turner's death his former colleague Isaiah Bowman had this to say of his work: "Turner's ideas were curiously wanting in evidence from field studies...He represents a type of historian who rests his case on documents and general impression rather than a scientist who goes out for to see."[11] His ideas were never forgotten; indeed they influenced the new field of environmental history.[12] Turner gave a strong impetus to quantitative methods, and scholars using new statistical techniques and data sets have, for example, confirmed many of Turner's suggestions about population movements.[13] Turner believed that because of his own biases and the amount of conflicting historical evidence that any one method of historical interpretation would be insufficient, that an interdisciplinary method was the most accurate way to analyze history.[14] WorksFrontier thesisTurner's frontier thesis was developed in a scholarly paper of 1893, "The Significance of the Frontier in American History", read before the American Historical Association in Chicago during the World's Columbian Exposition (Chicago World's Fair). He believed the spirit and success of the United States was associated directly with the country's westward expansion. Turner expounded an evolutionary model; he had been influenced by work with geologists at Wisconsin. The West, not the East, was where distinctively American characteristics emerged. The creation of the unique American identity occurred at the juncture between the "civilization" of settlement and the "savagery" of wilderness. This produced a new type of citizen – one with the power to "tame the wild" and one upon whom the wild had conferred strength and individuality.[15] As each generation of pioneers relocated 50 to 100 miles west, they abandoned useless European practices, institutions and ideas, and instead found new solutions to new problems created by their new environment. Over multiple generations, the frontier produced characteristics of informality, violence, crudeness, democracy and initiative that the world recognized as "American". Turner ignored gender, and he did not emphasize class. Historians of the 1960s and later stressed that race, class and gender were major influencers of history. The new generation stresses gender, ethnicity, professional categorization, and the contrasting victor and victim legacies of manifest destiny and colonial expansion. Most[citation needed] professional historians operating within the au courant postmodern paradigm now criticize Turner's frontier thesis and the theme of American exceptionalism. The disunity of the concept of the West and the similarity of American expansion to European colonialism and imperialism during the 19th century, and the lack of complete egalitarianism even on the frontier revealed the limits[clarification needed] of Turnerian and exceptionalist paradigms.[16] SectionalismTurner's sectionalism essays are collected in The Significance of Sections in American History, which won the Pulitzer Prize in History in 1933. Turner's sectionalism thesis had almost as much influence among historians as his frontier thesis, but never became widely known to the general public as did the frontier thesis. He argued that different ethnocultural groups had distinct settlement patterns, and this revealed itself in politics, economics and society.[5] Influence and legacyTurner's ideas influenced many types of historiography. Concerning the history of religion, for example, Boles (1993) notes that William Warren Sweet at the University of Chicago Divinity School argued that churches adapted to the characteristics of the frontier, creating new denominations such as the LDS Church, the Church of Christ, the Disciples of Christ, and the Cumberland Presbyterians. The frontier, they argued, created uniquely American institutions such as revivals, camp meetings, and itinerant preaching. This opinion dominated religious historiography for decades.[17] Moos (2002) says that the 1910s to 1940s black filmmaker and novelist Oscar Micheaux incorporated Turner's frontier thesis into his work. Micheaux promoted the West as a place where blacks could transcend race and earn economic success through diligent work and perseverance.[18] Citing Turner's "frontier thesis," Friedrich Ratzel believed that the German campaign to colonize German South West Africa could serve to "harden (the German) character."[19] Slatta (2001) maintains that the widespread popularization of Turner's frontier thesis influenced popular histories, motion pictures, and novels, which characterize the West in terms of individualism, frontier violence, and rough justice. Disneyland's Frontierland of the late 20th century represented the myth of rugged individualism that celebrated what was perceived to be the American heritage. The public has ignored academic historians', David J. Weber for example, anti-Turnerian models, largely because they conflict with and often destroy the legends of Western heritage. However, the work of historians during the 1980s–1990s, some of whom sought to discredit Turner's conception of the frontier and others who have sought to spare the concept while presenting a more balanced and nuanced version of it, have done much to place Western myths in context.[20] The Frederick Jackson Turner Award is given annually by the Organization of American Historians for an author's first scholarly book on American history.[21] Turner's former home in Madison, Wisconsin is located in what is now the Langdon Street Historic District. In 2009 he was inducted into the Hall of Great Westerners of the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum.[22] Marriage, family, and deathTurner married Caroline Mae Sherwood in Chicago in November 1889. They had three children: only one survived childhood. Dorothy Kinsley Turner (later Main) was the mother of the historian Jackson Turner Main (1917–2003), a scholar of Revolutionary America who married a fellow scholar. Frederick Jackson Turner died in 1932 in Pasadena, California,[1] where he had been a research associate at the Huntington Library. See also

Bibliography

References

Sources

Further reading

External linksWikimedia Commons has media related to Frederick Jackson Turner.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||