|

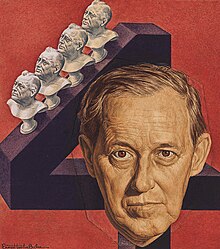

Harry Hopkins

Harold Lloyd Hopkins (August 17, 1890 – January 29, 1946) was an American statesman, public administrator, and presidential advisor. A trusted deputy to President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Hopkins directed New Deal relief programs before serving as the eighth United States secretary of commerce from 1938 to 1940 and as Roosevelt's chief foreign policy advisor and liaison to Allied leaders during World War II. During his career, Hopkins supervised the New York Temporary Emergency Relief Administration, the Federal Emergency Relief Administration, the Civil Works Administration, and the Works Progress Administration, which he built into the largest employer in the United States. He later oversaw the $50 billion Lend-Lease program of military aid to the Allies and, as Roosevelt's personal envoy, played a pivotal role in shaping the alliance between the United States and the United Kingdom. Born in Iowa, Hopkins settled in New York City after he graduated from Grinnell College. He accepted a position in New York City's Bureau of Child Welfare and worked for various social work and public health organizations. He was elected president of the National Association of Social Workers in 1923. In 1931, New York Temporary Emergency Relief Administration chairman Jesse I. Straus hired Hopkins as the agency's executive director. His successful leadership of the program earned the attention of then-New York Governor Roosevelt, who brought Hopkins into his federal administration after he won the 1932 presidential election. Hopkins enjoyed close relationships with President Roosevelt and First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, and was considered a potential successor to the president until the late 1930s, when his health began to decline due to a long-running battle with stomach cancer. As Roosevelt's closest confidant, Hopkins assumed a leading foreign policy role after the outset of World War II. From 1940 until 1943, Hopkins lived in the White House and assisted the president in the management of American foreign policy, particularly toward the United Kingdom and the Soviet Union. He traveled frequently to the United Kingdom, whose prime minister, Winston Churchill, recalled Hopkins in his memoirs as a "natural leader of men" with "a flaming soul." Hopkins attended the major conferences of the Allied powers, including the Casablanca Conference (January 1943), the Cairo Conference (November 1943), the Tehran Conference (November–December 1943), and the Yalta Conference (February 1945). His health continued to decline, and he died in 1946 at the age of 55. Early lifeHopkins was born at 512 Tenth Street in Sioux City, Iowa, the fourth child of four sons and one daughter of David Aldona and Anna (née Pickett) Hopkins. His father, born in Bangor, Maine, ran a harness shop (after an erratic career as a salesman, prospector, storekeeper, and bowling-alley operator), but his real passion was bowling, and he eventually returned to it as a business. Anna Hopkins, born in Hamilton, Ontario, had moved at an early age to Vermillion, South Dakota, where she married David. She was deeply religious and active in the affairs of the Methodist church. Shortly after Harry was born, the family moved successively to Council Bluffs, Iowa, and Kearney and Hastings, Nebraska. They spent two years in Chicago and finally settled in Grinnell, Iowa. Hopkins attended Grinnell College and soon after his graduation in 1912 took a job with Christodora House, a social settlement house in New York City's Lower East Side ghetto. In the spring of 1913, he accepted a position from John A. Kingsbury of the New York Association for Improving the Condition of the Poor (AICP) as a "friendly visitor" and superintendent of the Employment Bureau within the AICP's Department of Family Welfare. During the 1915 recession, Hopkins and the AICP's William Matthews, with $5,000 from Elizabeth Milbank Anderson's Milbank Memorial Fund, organized the Bronx Park Employment program, which was one of the first public employment programs in the US.[1] Social and public health workIn 1915, New York City Mayor John Purroy Mitchel appointed Hopkins executive secretary of the Bureau of Child Welfare which administered pensions to mothers with dependent children. Hopkins at first opposed America's entrance into World War I, but, when war was declared in 1917, he supported it enthusiastically. He was rejected for the draft because of a bad eye.[2] Hopkins moved to New Orleans where he worked for the American Red Cross as director of Civilian Relief, Gulf Division. Eventually, the Gulf Division of the Red Cross merged with the Southwestern Division and Hopkins, headquartered now in Atlanta, was appointed general manager in 1921. Hopkins helped draft a charter for the American Association of Social Workers (AASW) and was elected its president in 1923. In 1922, Hopkins returned to New York City, where the AICP was involved with the Milbank Memorial Fund and the State Charities Aid Association in running three health demonstrations in New York State. Hopkins became manager of the Bellevue-Yorkville health project and assistant director of the AICP. In mid-1924 he became executive director of the New York Tuberculosis Association. During his tenure, the agency grew enormously and absorbed the New York Heart Association.[3] In 1931, New York Governor Franklin D. Roosevelt named R. H. Macy's department store president Jesse Straus as president of the Temporary Emergency Relief Administration (TERA). Straus named Hopkins, then unknown to Roosevelt, as TERA's executive director. His efficient administration of the initial $20 million outlay to the agency gained Roosevelt's attention, and in 1932, he promoted Hopkins to the presidency of the agency.[4] Hopkins and Eleanor Roosevelt began a long friendship, which strengthened his role in relief programs.[5] New DealIn March 1933, Roosevelt summoned Hopkins to Washington as federal relief administrator. Convinced that paid work was psychologically more valuable than cash handouts, Hopkins sought to continue and expand New York State's work relief programs, the Temporary Emergency Relief Administration. He supervised the Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA), the Civil Works Administration (CWA), and the Works Progress Administration (WPA). Over 90% of the people employed by the Hopkins programs were unemployed or on relief. He feuded with Harold Ickes, who ran a rival program, the Public Works Administration, which also created jobs by contracting private construction firms, which did not require applicants to be unemployed or on relief.[6] FERA, the largest program from 1933 to 1935, involved giving money to localities to operate work relief projects to employ those on direct relief. CWA was similar but did not require workers to be on relief to receive a government-sponsored job. In less than four months, the CWA hired four million people, and during its five months of operation, the CWA built and repaired 200 swimming pools, 3,700 playgrounds, 40,000 schools, 250,000 miles (400,000 km) of road, and 12 million feet of sewer pipe. The WPA, which followed the CWA, employed 8.5 million people in its seven-year history, working on 1.4 million projects, including the building or repair of 103 golf courses, 1,000 airports, 2,500 hospitals, 2,500 sports stadiums, 3,900 schools, 8,192 parks, 12,800 playgrounds, 124,031 bridges, 125,110 public buildings, and 651,087 miles (1,047,823 km) of highways and roads. The WPA operated on its own on selected projects in co-operation with local and state governments, but always with its own staff and budget. Hopkins started programs for youth (National Youth Administration) and for artists and writers (Federal One Programs). Hopkins and Eleanor Roosevelt worked together to publicize and defend New Deal relief programs. He was concerned with rural areas but increasingly focused on cities in the Great Depression.[7] In the years after he resigned, Hopkins expressed pride in the WPA's key role in building internment camps for Japanese Americans. On March 19, 1942, for example, he lauded Howard O. Hunter, the head of the WPA at that time, for the "building of those camps for War Department for the Japanese evacuees on the West Coast."[8] Before Hopkins began to decline from his struggle with stomach cancer in the late 1930s, Roosevelt appeared to be training him as a possible successor.[9] With the advent of World War II in Europe, however, Roosevelt ran again in 1940 and won an unprecedented third term.[10] World War II On May 10, 1940, after a long night and day spent discussing the German invasion of the Netherlands, Belgium, and Luxembourg that had ended the so-called "Phoney War," Roosevelt urged a tired Hopkins to stay for dinner and then the night in a second-floor White House bedroom. Hopkins would live out of the bedroom for the next three-and-a-half years.[11][12] On December 7, 1941, at 1:40 pm, Hopkins was in the Oval Study, in the White House, having lunch with President Roosevelt, when Roosevelt received the first report that Pearl Harbor had been attacked via phone from Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox.[13] Initially, Hopkins was skeptical of the news until Chief of Naval Operations Adm. Harold Rainsford Stark called a few minutes later to confirm Pearl Harbor had in fact been attacked.   During the war years, Hopkins acted as Roosevelt's chief emissary to British Prime Minister Winston Churchill. In January 1941, Roosevelt dispatched Hopkins to assess Britain's determination and situation. Churchill escorted the important visitor all over the United Kingdom. Before he returned, at a small dinner party in the North British Hotel, Glasgow, Hopkins rose to propose a toast: "I suppose you wish to know what I am going to say to President Roosevelt on my return. Well I am going to quote to you one verse from the Book of Ruth ... 'Whither thou goest, I will go and where thou lodgest I will lodge, thy people shall be my people, and thy God my God.'"[14] [15] Hopkins became the administrator of the Lend-Lease program, under which the United States gave to Britain and Soviet Union, China, and other Allied nations food, oil, and materiel including warships, warplanes and weaponry. Repayment was primarily in the form of Allied military action against the enemy, as well as leases on army and naval bases in Allied territory used by American forces. Hopkins had a major voice in policy for the vast $50 billion Lend-Lease program, especially regarding supplies, first for Britain and then, upon the German invasion, the Soviets. He went to Moscow in July 1941 to make personal contact with Joseph Stalin. Hopkins recommended and Roosevelt accepted the inclusion of the Soviets in Lend Lease. Hopkins made Lend Lease decisions in terms of Roosevelt's broad foreign policy goals.[16] He accompanied Churchill to the Atlantic Conference. Hopkins promoted an aggressive war against Germany and successfully urged Roosevelt to use the Navy to protect convoys headed for Britain before the US had entered the war in December 1941. Roosevelt brought him along as advisor to his meetings with Churchill and Stalin at Cairo, Tehran, Casablanca in 1942–43, and Yalta in 1945. He was a firm supporter of China, which received Lend-Lease aid for its military and air force. Hopkins wielded more diplomatic power than the entire State Department. Hopkins helped identify and sponsor numerous potential leaders, including Dwight D. Eisenhower.[17] He continued to live in the White House and saw the President more often than any other advisor. In mid-1943, Hopkins faced a barrage of criticism from Republicans and the press that he had abused his position for personal profit. One Representative asserted that British media tycoon Lord Beaverbrook had given Hopkins's wife, Louise, $500,000 worth of emeralds, which Louise denied. Newspapers ran stories detailing sumptuous dinners that Hopkins attended while he was making public calls for sacrifice. Hopkins briefly considered suing the Chicago Tribune for libel after a story that compared him to Grigory Rasputin, the famous courtier of Tsar Nicholas II of Russia, but he was dissuaded by Roosevelt.[18] Although Hopkins's health was steadily declining, Roosevelt sent him on additional trips to Europe in 1945. Hopkins attended the Yalta Conference in February 1945. He tried to resign after Roosevelt died, but President Harry S. Truman sent Hopkins on one more mission to Moscow. Hopkins met with Stalin in late May to secure reassurances on Soviet involvement in the Pacific theater and to arrange concessions on the Soviet sphere of influence in postwar Poland.[19] Hopkins had three sons who served in the armed forces during the war: Robert, David and Stephen. Stephen was killed in action while he was serving in the Marine Corps.[20] Relations with Soviet Union Hopkins was the top American official assigned to dealing with Soviet officials during World War II. He liaised with Soviet officials from the middle ranks to the very highest, including Stalin. Anastas Mikoyan was Hopkins' counterpart with responsibility for Lend-Lease. He often explained Roosevelt's plans to Stalin and other top Soviet officials to enlist Soviet support for American objectives, an endeavor that met with limited success. A particularly striking example of bad faith was Moscow's refusal to allow American naval experts to see the German experimental U-boat station at Gdynia captured on March 28, 1945, and thus to help the protection of the very convoys that carried Lend-Lease aid.[21] In turn, Hopkins passed on Stalin's stated goals and needs to Roosevelt. As the top American decision maker in Lend-Lease, he gave priority to supplying the Soviet Union, despite repeated objections from Republicans. As Soviet soldiers were bearing the brunt of the war, Hopkins felt that American aid to the Soviets would hasten the war's conclusion.[22] On August 10, 1943, he spoke about the USSR's decisive role in the war, saying that "Without Russia in the war, the Axis cannot be defeated in Europe, and the position of the United Nations becomes precarious. Similarly, Russia's post-war position in Europe will be a dominant one. With Germany crushed, there is no power in Europe to oppose her tremendous military forces."[23] Hopkins continued to be a target of attacks even after his death. George Racey Jordan testified to the House Un-American Activities Committee in December 1949 that Hopkins passed nuclear secrets to the Soviets. Historians do not cite Jordan as credible since at the time Jordan claimed to have met with Hopkins in Washington regarding uranium shipments, Hopkins was in intensive care at the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota. In 1963, the FBI concluded that Jordan "either lied for publicity and profit or was delusional."[24] According to historian Sean McMeekin, in his recent book Stalin’s War (2021), “Many US lend-lease records, including the correspondence of Hopkins and Edward Stettinius Jr and the minutes of the Soviet protocol committee, were declassified in the 1970s, long after opinions about Soviet espionage had hardened into dogma. These files are now open, and they confirm the veracity of nearly all of Jordan’s claims, except for his allegation that Hopkins’s actions were illegal”.[25]  It is likely that any Soviets who spoke to Hopkins would have been routinely required to report the contact to the NKVD, the Soviet national security agency. Eduard Mark (1998) says that some Soviets, such as spymaster Iskhak Akhmerov, thought that Hopkins was pro-Soviet, but others thought that he was not.[26] Verne W. Newton, the author of FDR and the Holocaust, said that no writer discussing Hopkins has identified any secrets disclosed or any decision in which he distorted American priorities to help communism.[27] As Mark demonstrated, Hopkins was not pro-Soviet in his recommendations to Roosevelt; he was anti-German and pro-American. Any "secrets" disclosed were authorized. Mark says that at the time, any actions were taken specifically to help the American war effort and to prevent the Soviets from making a deal with Hitler.[28] It is currently considered likely that Laurence Duggan was the titular agent "19" mentioned in the Venona Project decryptions of Soviet cables.[29][30] Hopkins may simply have been naïve in his estimation of Soviet intentions. The historian Robert Conquest wrote that "Hopkins seems just to have accepted an absurdly fallacious stereotype of Soviet motivation, without making any attempt whatever to think, or to study the readily available evidence, or to seek the judgement of the knowledgeable. He conducted policy vis-a-vis Stalin with mere dogmatic confidence in his own (and his circle's) unshakeable sentiments."[31] Personal lifeIn 1913, Hopkins married Ethel Gross (1886–1976), a Hungarian-Jewish immigrant active in New York City's Progressive movement. They had three sons: David, Robert, and Stephen,[32] (they had lost an infant daughter to whooping cough)[33] and though Gross divorced Hopkins in 1930 shortly before Hopkins became a public figure, the two kept up an intimate correspondence until 1945.[34][35][36] In 1931, Hopkins married Barbara Duncan, who died of cancer six years later.[35] They had one daughter, Diana (1932–2020).[37] In 1942, Hopkins married Louise Gill Macy (1906–1963) in the Yellow Oval Room at the White House.[38] Macy was a divorced, gregarious former editor for Harper's Bazaar. The two continued to live at the White House at Roosevelt's request,[39] though Louise eventually demanded a home of their own. Hopkins ended his long White House stay on December 21, 1943, moving with his wife to a Georgetown townhouse.[40] Cancer and deathIn mid-1939, Hopkins was told that he had stomach cancer, and doctors performed an extensive operation that removed 75% of his stomach. What remained of Hopkins's stomach struggled to digest proteins and fat, and a few months after the operation, doctors stated that he had only four weeks to live. At this point, Roosevelt brought in experts, who transfused Hopkins with blood plasma that halted his deterioration. When the "Phoney War" phase of World War II ended in May 1940, the situation galvanized Hopkins; as Doris Kearns Goodwin wrote, "the curative impact of Hopkins' increasingly crucial role in the war effort was to postpone the sentence of death the doctors had given him for five more years".[41] Though his death has been attributed to his stomach cancer, some historians have suggested that it was the cumulative malnutrition related to his post-cancer digestive problems. Another suggestion is that Hopkins died from liver failure due to hepatitis or cirrhosis,[42] but Robert Sherwood authoritatively reported that Hopkins' postmortem examination showed the cause of death was hemosiderosis[43] due to hepatic iron accumulation from his many blood transfusions and iron supplements. James A. Halsted, a medical doctor, noted nutrition researcher, and the third husband of Franklin D. Roosevelt's daughter Anna Roosevelt Halsted,[44] concluded that "in light of all the available facts up to his death in 1946, it seems justifiable to speculate that he had non-tropical sprue or adult celiac disease (gluten enteropathy)."[45] Hopkins died in New York City on January 29, 1946, at the age of 55. His body was cremated and his ashes interred in his former college town at the Hazelwood Cemetery in Grinnell, Iowa. There is a house on the Grinnell College campus named after him and his childhood home, with a plaque, is located at Sixth Avenue and Elm Street. References

West, Diana. "American Betrayal" =(2014) Further reading

External links

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||