|

Hurricane Felicia (2009)

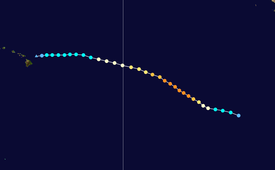

Hurricane Felicia was a powerful Category 4 Pacific hurricane whose remnants caused significant rainfall and flooding on the Hawaiian Islands. Felicia was the third strongest tropical cyclone of the 2009 Pacific hurricane season, as well as the strongest storm to exist in the eastern Pacific at the time since Hurricane Daniel in 2006.[1][2] Forming as a tropical depression on August 3, the storm supported strong thunderstorm activity and quickly organized. It became a tropical storm over the following day, and subsequently underwent rapid deepening to attain hurricane status. Later that afternoon, Felicia developed a well-defined eye as its winds sharply rose to major hurricane-force on the Saffir–Simpson scale. Further strengthening ensued, and Felicia peaked in intensity as a Category 4 hurricane with sustained winds of 145 mph (233 km/h) and a barometric pressure of 935 mbar (hPa; 27.61 inHg). After reaching this strength, unfavorable conditions, such as wind shear, began to impact the storm while it took on a northwestward path. Henceforth, Felicia slowly weakened for several days; by August 8 it had been downgraded to a Category 1 hurricane, once again becoming a tropical storm the next day. It retraced westward towards Hawaii on August 10, all the while decreasing in organization. On August 11, Felicia weakened to tropical depression status, and soon degenerated into remnant low just prior to passing over the islands. After weakening into a remnant low, Felicia continued to approach the Hawaiian Islands and on August 12, the system produced copious amounts of rainfall across several islands. The highest total was recorded on Oahu at 14.63 in (372 mm), causing isolated mudslides and flooding. In Maui, the heavy rains helped to alleviate drought conditions and water shortages, significantly increasing the total water across the island's reservoirs. In addition, river flooding resulted in the closure of one school and large swells produced by the storm resulted in several lifeguard rescues at island beaches. In all, only minor impacts were caused by the remnants of Felicia. Meteorological history Map key Tropical depression (≤38 mph, ≤62 km/h) Tropical storm (39–73 mph, 63–118 km/h) Category 1 (74–95 mph, 119–153 km/h) Category 2 (96–110 mph, 154–177 km/h) Category 3 (111–129 mph, 178–208 km/h) Category 4 (130–156 mph, 209–251 km/h) Category 5 (≥157 mph, ≥252 km/h) Unknown Storm type Hurricane Felicia originated from a tropical wave that moved off the west coast of Africa into the Atlantic Ocean on July 23, 2009. A weak system, the wave was barely identifiable as it tracked westward. By July 26, the wave entered the Caribbean before crossing Central America and entering the eastern Pacific basin on July 29. The system remained ill-defined until August 1, at which time convection began to increase and the wave showed signs of organization.[3] The storm gradually became better organized as it tracked generally towards the west.[4] By August 3, the system became increasingly organized[5] and around 11:00 am PDT (1800 UTC), the National Hurricane Center (NHC) designated the system as Tropical Depression Eight-E.[3][6] Convective banding features and poleward outflow were being enhanced by the nearby Tropical Storm Enrique. The main steering component of the depression was an upper-level low located to the north, causing the depression to track generally west before turning northwest after the low weakened.[7] By the early morning hours of August 4, the NHC upgraded Tropical Depression Eight-E to Tropical Storm Felicia, the seventh named storm of the season.[1][8] Located within an area of low wind shear and high sea surface temperatures, averaging between 28 and 29 °C (82 and 84 °F),[3] the storm quickly developed, with deep convection persisting around the center of circulation. These conditions were anticipated to persist for at least three days; however, there was an increased amount of uncertainty due to possible interaction with Tropical Storm Enrique.[9] Several hours later, the storm began to undergo rapid intensification, following the formation of an eye.[10] Around 2:00 pm PDT (2100 UTC), Felicia intensified into a hurricane.[11]  Late on August 4, the intensity of Felicia led to it taking a more northward turn in response to a mid- to upper-level trough off the coast of the Western United States.[12] Early the next morning, the storm continued to intensify and attained Category 3 status with winds of 115 mph (185 km/h).[13] Maintaining a well-defined eye, Felicia neared Category 4 status[14] and hours later, the storm attained winds of 140 mph (230 km/h) and a pressure of 937 mbar (hPa; 27.67 inHg) during the evening hours, making it the strongest Pacific storm east of the International Date Line since Hurricane Ioke in 2006[1][15] and the strongest in the eastern Pacific basin since Hurricane Daniel of 2006.[1][2] Around 5:00 pm PDT (0000 UTC August 6) Felicia reached its peak intensity with winds of 145 mph (233 km/h) and a minimum central pressure of 935 mbar (hPa; 27.61 inHg).[2][3] After slightly weakening throughout the day on August 6, Felicia leveled out with winds of 135 mph (217 km/h) and a 23 mi (37 km) wide eye[16] as the storm developed characteristics of an annular hurricane, which would allow Felicia to maintain a high intensity over marginally warm waters.[17] Early the next day, the structure of the hurricane quickly deteriorated as convection became asymmetric and cloud tops warmed significantly. This marked a quick drop in intensity of the storm to a minimal Category 3 hurricane.[18] Several hours later, the mid-level circulation began to separate from the low-level circulation and the overall size of the storm decreased. By this time, the storm began to take a long-anticipated westward turn towards Hawaii.[19] After briefly re-intensifying on August 7, Felicia weakened to a Category 1 hurricane early on August 8.[20][21] Around 11:00 am HST (2100 UTC), the Central Pacific Hurricane Center (CPHC) took over responsibility of issuing advisories as Felicia crossed longitude 140°W.[22] By August 9, increasing wind shear further weakened the storm, with Felicia being downgraded to a tropical storm early that day.[23] The storm rapidly weakened throughout the day as convection gradually dissipated around the center due to the shear. By the late morning hours, little convective activity remained around the low pressure center of Felicia.[24] A weak cyclone, the storm continued to track towards Hawaii with the only deep convection associated with it being displaced to the northeast of the center.[25] The system slowly weakened before being downgraded to a tropical depression on August 11 as no areas of tropical storm-force winds were found by hurricane hunters.[26] Several hours after being downgraded, the CPHC issued its final advisory on Felicia as it degenerated into a remnant low near the Hawaiian Islands.[27] The system dissipated shortly thereafter.[3] Preparations

By August 5, forecasters were discussing the possibility of the storm impacting Hawaii.[37] Residents were advised to ensure that their disaster kits were fully stocked and ready.[38] Governor Linda Lingle made a speech to the state of Hawaii the same day. She emphasized that the storm was not an imminent threat but that residents should be ready and should know where the nearest emergency shelter is.[39] Since forecasters expected the storm to weaken before it reached the islands, only minor effects—mainly rainfall—were expected.[40] Hawaii County mayor Billy Kenoi was also briefed on the approaching storm and he advised the county to be prepared.[41] Stores reported an influx of shoppers and posted anniversary sales. Blue tarps for roofs were being sold at $1 apiece. The American Red Cross also reported that sales of the "water bob", a water container that can be attached to a bathtub and hold roughly 100 gallons of water, increased significantly.[42] On August 6, the Red Cross stated that it was deploying a disaster recovery team, led by the director of the agency, to the islands of Hawaii.[43] On August 7, five Hurricane Hunter planes were dispatched to Hickam Air Force Base to fly missions into the storm.[44] Later that day, the Central Pacific Hurricane Center issued tropical storm watches for the island of Hawaii, Maui, Kahoolawe, Lanai, and Molokai.[45] On August 9, the watch was expanded to include Oahu.[46] The watches for the Big Island were later cancelled as the forecast track appeared to drift further north toward Maui County and Oahu.[47] The Red Cross opened shelters throughout the islands on August 10. Twelve were on the Big Island, seven were on Maui, two on Molokai and one on Lanai.[48] The Honolulu International Airport ensured that eight generators were ready for use in case Felicia caused a power outage at the airport.[49] All tropical storm watches were cancelled at 11 a.m. August 11 as Felicia dissipated to a remnant low.[50] Impact OahuIn Oahu, areas on the windward side of the island received more than 1 in (25 mm) of rain on August 12 from the remnants of Felicia, causing many roads to become slick.[51] A portion of Kamehameha Highway was shut down around 11:00 pm HST when the Waikane Stream overflowed its banks. Flooding near a bridge reached a depth of 4 ft (1.2 m), stranding some residents in their homes. The highway remained closed until around 4:00 am HST on August 14. The rain was also considered helpful in that it helped alleviate drought conditions that had been present for nearly two months.[52] The heaviest rainfall was recorded on Oahu at 14.63 in (372 mm) in the Forest National Wildlife Refuge.[53][54] During a 12-hour span, a total of 6.34 in (161 mm) fell in Waiahole.[55] Some areas recorded rainfall rates up to 1 in/h (25 mm/h), triggering isolated mudslides.[56] At Sandy Beach, there were two lifeguard rescues and three others were on Makapuʻu as waves up to 18 ft (5.5 m) affected the islands.[57] There were also five assists at Makapuʻu and one at Kailua Beach. Lifeguards issued a total of 1,410 verbal warnings about the rough seas to swimmers and surfers during the event.[58] However, winds on the island reached only 15 mph (24 km/h) and gusts peaked at 20 mph (32 km/h).[59] Other islands On Kauai, the Hanalei River rose above its normal level, leading to the closure of the Hanalei School. Several tree limbs and small trees were blown down across the island. Rainfall on Kauai peaked at 5.33 in (135 mm) at Mount Wai'ale'ale and on Maui, up to 4.05 in (103 mm) fell in Kaupo Gap.[60] On the leeward side of the mountains, rainfall peaked at 1.3 in (33 mm) in Kihei, an area that rarely records rainfall in August. Throughout the island, the total amount of water in reservoirs increased to 104.5 million gallons (395.5 million liters) from 77.8 million gallons (294.5 million liters) prior to Felicia.[61] Rainfall in some areas was heavy enough at times to reduce visibility to several feet. Streets in these areas were covered with muddy water.[62] Localized heavy rainfall fell on the Big Island, peaking at 2.76 in (70 mm) in Kealakekua.[55] In Wailua Beach, there was one lifeguard rescue that resulted in the swimmer being sent to a local hospital. Three other people were swept away at the mouth of the Wailua River, all of whom were quickly rescued.[63] In Honolulu, runoff from the storm resulted in large amounts of trash and debris along the local beaches. Private contractors were dispatched to the affected coastlines to trap and remove the trash.[64] Officials were forced to close the beaches along Hanauma Bay after swells from Felicia pushed an estimated 2,000 Portuguese Man o' War siphonophorae into the region. The beaches were later re-opened on August 14.[65] See also

References

External linksWikimedia Commons has media related to Hurricane Felicia (2009). Wikinews has related news:

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||