|

June (magazine)

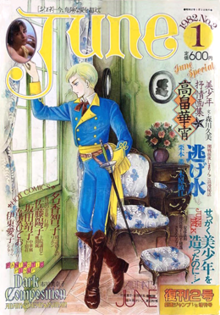

June (Japanese: ジュネ, [d͡ʑu͍ ne]) was a Japanese magazine focused on shōnen-ai, a genre of male-male romance fiction aimed at a female audience. It was the first commercially published shōnen-ai magazine, launching in October 1978 under the title Comic Jun and ceasing publication in November 1995. June primarily published manga and prose fiction, but also published articles on films and literature, as well as contributions from readers. The magazine spawned multiple spin-off publications, notably Shōsetsu June ('Novel June') and Comic June. June targeted a readership of women in their late teens and early twenties, and at its peak had a circulation of approximately 80,000 copies. In addition to publishing established manga artists and writers such as Keiko Takemiya, Azusa Nakajima, Akimi Yoshida, and Fumi Saimon, the magazine launched the careers of artists and novelists such as Masami Tsuda and Marimo Ragawa from submissions curated and edited by Takemiya and Nakajima. As a nationally distributed commercial magazine, June is credited with disseminating and systemizing shōnen-ai in Japan, a genre which had largely been confined to relatively narrow outlets such as doujinshi conventions (events for the sale of self-published media). The term "June" and the magazine's central editorial concept of tanbi (lit. 'aestheticism') became popular generic terms for works depicting male homosexuality, which influenced the later male-male romance genres of yaoi and boys' love (BL). HistoryFirst issue to temporary suspension June was conceived by Toshihiko Sagawa, then a part-time worker at Sun Publishing.[1][a] An avid manga reader, Sagawa was intrigued by depictions of homoeroticism and bishōnen (lit. "beautiful boys", a term for androgynous men) in manga by the Year 24 Group, and submitted a proposal to Sun Publishing for a "mildly pornographic magazine for women".[1][3] The proposal was accepted, and the first issue of the magazine launched under the title Comic Jun in October 1978.[4] "Jun" was derived from the manga series Jun: Shotaro no Fantasy World by Shotaro Ishinomori, as well as from the Japanese word jun (純), meaning "purity". The first issue was priced at 380 yen, a high price for magazines at the time.[5] The founding editor of the magazine was Tetsuro Sakuragi, who had previously served as the editor of Sabu, a gay men's magazine also published by Sun Publishing.[1] Sagawa recruited manga artist Keiko Takemiya – a central figure in the Year 24 Group – and novelist Azusa Nakajima as contributors.[6] Takemiya stated that she chose to participate in Comic Jun to provide "covering fire" for her shōnen-ai manga series Kaze to Ki no Uta, which was being serialized in Shūkan Shōjo Comic at the time.[7][b] Nakajima was a senior member of the Waseda Mystery Club, to which Sagawa belonged when he was a student at Waseda University.[8] The magazine was renamed June beginning with its third issue in February 1979 due to a conflict with the Japanese fashion brand Jun.[9][10] As the dispute arose while printing for the third issue had already begun, an "E" was hastily added at the end of the magazine's title at the suggestion of the president of Sun Publishing.[10][11][c] As sales forecasts were not undertaken for early issues, more than 100,000 copies of the first issue were printed, resulting in many returns and unsold copies.[11] Though sales gradually improved,[15] low sales forced June to cease publication after the release of its August 1979 issue.[11] Relaunch and Shōsetsu JuneAfter ceasing publication of June, Sun Publishing received an influx of letters from readers indicating that they were willing to pay up to 1,000 yen for issues of the magazine.[5] In response, Sun Publishing relaunched the magazine in October 1981, cutting its circulation by half and doubling its price to 760 yen.[16] The first relaunched issue was published as a special issue of Gekiga Jump, a magazine also published by Sun Publishing.[17] Shōsetsu June ('Novel June'), which primarily published prose fiction and serial novels, began to be published as a sister publication beginning with the October 1982 issue of June.[18] Shōsetsu June was nicknamed "Ko-June" ('Little June') while June was nicknamed "Dai-June" ('Big June').[10] Ironically, circulation of Shōsetsu June quickly surpassed that of June;[15] beginning in February 1984, Shōsetsu June became a bimonthly publication.[1][18] Discontinuation and spin-off magazinesIn the late 1980s, yaoi doujinshi (self-published manga and books) grew rapidly in popularity, and in the 1990s "boys' love" (BL) was established as a commercial male-male romance genre.[19] Sales of June consequently began to decline beginning in the 1990s,[20] and the magazine ceased publication with its 85th issue in November 1995.[10][19] Sagawa stated that he initially believed that June, which primarily depicted romance stories, could co-exist with the more explicitly pornographic yaoi and BL genres, though this was ultimately not the case.[21] Following the discontinuation of June, prose fiction was integrated into Shōsetsu June, while manga content was split into two magazines: June Shinsengumi ('June Fresh Group') and Comic June.[18][d] In contrast to the shōnen-ai of June, Comic June published primarily sexually explicit BL manga.[23] In 1996, Visualtambi June launched as a general interest magazine focused on gravures (pin-up photography), reader contributions, and information about doujinshi, but ceased publication after its second issue in April that same year.[18] In 1997, a one-off magazine titled Comic Bishōnen was published as a special issue of Shōsetsu June.[24] Sun Publishing also sold a variety of paperback manga books, audio cassettes, CDs, and original video animations under the June brand.[25] Circulation of Shōsetsu June began to steadily decline in the late 1990s, after its popular serialization Fujimi Orchestra concluded and paperback editions began to eclipse the popularity of magazines as a medium for male-male romance fiction.[20] Shōsetsu June ceased publication with its 153rd issue published in April 2004,[10] while Comic June ceased publication in February 2013.[18][26] PublishingEditorial conceptSagawa used the word tanbi (耽美, lit. "aestheticism") to describe the editorial concept of June from its inception; the first issue of Comic Jun was subtitled with the slogan "Aesthetic Magazine For Gals", and the gravure photo section was titled Tanbi Sashin-kan (耽美写真館, transl. 'Aesthetic Photo Studio').[6] In the context of male-male romance fiction, tanbi broadly refers to Japanese aestheticism as it relates to an ideal of male beauty defined by fragility, sensitivity, and delicateness.[27] Sagawa was specifically inspired by the bishōnen and recurring themes of beauty and aestheticism in works by the Year 24 Group.[6] While the June conception of tanbi initially referred to adolescent bishōnen exclusively, it gradually widened to include young men and middle-aged men; by the early 1990s, tanbi was used broadly to refer to works that depicted male homosexuality.[28][e] ContributorsJune sought to have an underground, "cultish, guerilla-style" feeling – most of its contributors were new and amateur talent – with writer Frederik L. Schodt describing June as "a kind of 'readers' magazine, created by and for the readers."[3] June operated as a tōkō zasshi (a magazine which mainly publishes unsolicited manuscripts for a small honorarium), a model that it maintained even after the emergence of more formalized yaoi and BL magazines in the 1990s that published commissioned stories by professional writers.[31] The contributors to June were primarily manga artists associated with the Year 24 Group, doujinshi artists active at Comiket, and artists who had contributed to Sabu.[32] Keiko Takemiya contributed original manga and illustrations, while Azusa Nakajima contributed essays relating to the topic of shōnen-ai and novels under various pen names.[33] Regular contributors included Yasuko Aoike, Yasuko Sakata, Aiko Itō, and Yuko Kishi.[34] Other contributors included Mutsumi Inomata, Fumi Saimon, Suehiro Maruo, Akimi Yoshida, Fumiko Takano, Akemi Matsuzaki, and Michio Hisauchi.[17][33][35] Translator Tomoyo Kurihara oversaw the literature section,[36] while illustrator Chiyo Kurihara contributed an illustration column.[34] ContentJune primarily published manga and prose fiction, but also published articles on films, reading guides, and interviews with idols.[11] Articles on literature and fine art were also common, especially in early issues of the magazine.[19] The regular section "Junetopia" published articles and illustrations submitted by readers, as well as interviews with doujinshi circles (groups that create doujinshi).[37] The magazine contained few advertisements,[38] but did print reproductions of advertisements featuring attractive men or gay subject material.[39][f] Most works published in June depicted male-male romance, though the magazine occasionally depicted romance between androgynous characters, or between women.[2][g] According to Takemiya, an understanding was made with Sagawa that even heterosexual romance stories could be published in the magazine, so long as they conformed to the "June style".[41] The magazine did publish some fetishistic content; according to Nakajima, sadomasochism appeared in some early June stories,[42] while necrophilia and incest appeared in some in later June stories.[43] Media scholar Akiko Mizoguchi notes how the "semi-amateurish" quality of June engendered by its status as a tōkō zasshi meant that it was able to publish works that were more experimental relative to its male-male romance magazine contemporaries: works that were less heteronormative, that were not obliged to feature sex scenes, and which featured female and supporting characters.[44] Manga scholar Yukari Fujimoto describes works published in June as "aesthetic and serious".[45] Many early works published in June had tragic endings, with common themes and subjects including heartbreak, accidental death, and forced separation;[46] ten of the eleven works published in the first issue of Comic Jun ended in tragedy.[47] Happy endings were more common in June stories in the 1990s, such as the confirmation of mutual love or the beginning of a life together.[20][h] Cover artworkKeiko Takemiya served as cover illustrator for roughly the first decade of June's publication.[1] In an interview, Sagawa stated that he doubted that June would have been a success without Takemiya's cover illustrations.[11] Takemiya initially felt that her artistic style was not suited to the editorial material of June because it was bright and did not depict shadows, so she consciously drew shadows to match the June style.[49] Each of Takemiya's covers contains a simple self-contained narrative, such as an image of a crying boy, which Takemiya stated was a style unique to June relative to other manga magazines aimed at women.[50] After Takemiya stepped down as cover illustrator, the cover was created on a rotating basis by artists serialized in the magazine, including Yuko Kishi, Keiko Nishi, Mutsumi Inomata, and Akimi Yoshida.[51] Recurring sectionsKēko-tan no Oekaki Kyōshitsu"Kēko-tan no Oekaki Kyōshitsu" (ケーコタンのお絵描き教室, 'Keko-tan's Drawing School'), a section of June edited by Keiko Takemiya focused on instructing amateur artists in writing and illustrating manga, debuted in the second issue of the relaunched edition of June in January 1982.[52] The first occurrence of the section detailed how to draw men's lips, while the second detailed how to draw men's hands. From the January 1985 issue of the onwards, the section began publishing submissions from readers, which Takemiya would edit and provide feedback on.[52] Submissions were accepted so long as the subject material was "June-like", though a condition was later imposed that the work could be no longer than eight pages in length.[53] The section was conceived by Sagawa and inspired by the manga magazine COM, which had a similar editorial practice of publishing submissions from novice artists for the purpose of education and talent development.[54] Keiko Nishi, who would go on to become a professional manga artist, was published for the first time as an amateur in "Kēko-tan no Oekaki Kyōshitsu".[54] Shōsetsu DōjōEdited by Azusa Nakajima, "Shōsetsu Dōjō" (小説道場, 'Novel Dojo') debuted as a monthly section of the magazine in the January 1984 issue.[52] In the section, Nakajima explained literary devices, her process as a writer, and gave brief reviews to submissions from readers.[55][56] In her reviews, Nakajima assigned a grade to each submission based on its quality, with a black belt being the highest grade.[27] The section was among the most popular features in June;[57] Sagawa stated that he believed the section was so popular because while many readers had ideas for stories, the majority were likely unable to draw manga. The section is credited with helping to establish male-male romance as a literary genre in Japan, and launched the careers of male-male romance writers Akira Tatsumiya and Yuuri Eda.[58] Secret BunkoThe "Secret Bunko" (シークレット文庫, 'Secret Library') was a story whose pages were bound and sealed into the outer edge and spine of the magazine, such that it could not be read unless the reader purchased the magazine and tore the relevant pages out. The section was designed in part as a sales gimmick to combat tachiyomi, or "standing reading", the practice of browsing a magazine in a store without purchasing it.[39] The story in each "Secret Bunko" was billed as the "hottest" in each issue, though academic Sandra Buckley notes that the stories were typically "only marginally 'hotter' than those in the rest of the magazine".[39] Buckley notes that stories in the "Secret Bunko" were typically more violent than other stories in June, depicting "sexual contact in a more sinister or threatening way" compared to the "highly stylized romanticism" typical of the magazine's other editorial output.[39] Audience and circulationJune targeted an audience of women in their late teens to early twenties,[59] though its readership extended as far as women in their forties,[60] many of whom began reading June in their youth and continued doing so into adulthood.[27] Sagawa stated that his impression of the average June reader was a girl in high school or university who was intellectual, literary, and cultured.[61] Both Sagawa and Keiko Takemiya indicated their belief that many of the readers of June broadly felt a lack of social belonging, and in some cases had experienced specific trauma or abuse, and specifically sought stories of idealized male-male romance to serve a "therapeutic" function in ameliorating that trauma.[27][62][63] June also had a minority of male readers, including gay men.[61][64][i] According to the Zasshi Shinbun Sōkatarogu (雑誌新聞総かたろぐ, 'General Tabulation of Magazines and Newspapers') published by the Media Research Center, the circulation of June was 60,000 from 1983 to 1987, 70,000 from 1988 to 1989, and 100,000 from 1990 to 1995; Shōsetsu June had a circulation of 65,000 from 1985 to 1987, 80,000 from 1988 to 1989, and 100,000 from 1990 to 2004.[66] However, according to Sagawa, the circulation figures published in Zasshi Shinbun Sōkatarogu were exaggerated: the circulation of June never exceeded 80,000 copies, and averaged in the range of 40,000 to 60,000.[15] Miki Eibo, who served as editor-in-chief of June from 1993 to 2004, concurred that the circulation figures for June in Zasshi Shinbun Sōkatarogu were exaggerated, but that the figure of 100,000 for Shōsetsu June from 1992 to 1993 was close to the actual figure.[15] ImpactJune was the first commercially published shōnen-ai magazine,[8][67] and one of the only commercial magazines dedicated to this genre in the 1970s and 1980s.[68][j] Previously, shōnen-ai had been confined to the realm of doujinshi convention and other avenues with relatively limited reach, but with the creation of June as a nationally distributed commercial magazine, the genre was rapidly disseminated and systemized across Japan.[71] The popularity and influence of June was such that the term "June" and the magazine's central editorial concept of tanbi became popular generic terms to designate works depicting male homosexuality, which influenced the later male-male romance genres of yaoi and boys' love (BL).[28][72] Even after June ceased publication, the terms June-kei ('June-type') and June-mono ('June things') remained in use to designate male-male romance works that depicted tragedy, aestheticism, and other themes and subjects reminiscent of the works published in June.[13][45] Further, the magazine's coverage of gay culture is credited with influencing the gay community in Japan, with Sandra Buckley crediting June with "play[ing] a role in the construction of a collective gay identity" in Japan,[73] and academic Ishida Hitoshi describing June as a "queer contact zone" between the gay community and female manga readers.[13] Media scholar Akiko Mizoguchi divides the history of Japanese male-male romance fiction for women into three periods: the "genesis period", the "June period", and the "BL period".[74] According to Mizoguchi, June played a crucial role in producing a field of professional BL creators;[75] the magazine launched the careers of manga artists Keiko Nishi, Masami Tsuda, and Marimo Ragawa, and novelists Koo Akizuki and Eda Yuuri.[76] Gay manga artist Gengoroh Tagame made his debut as a manga artist in June, submitting a story under a pen name while in high school.[12] J.Garden, a male-male doujinshi convention in Japan, derives its name from June.[13] Notes

References

Bibliography

|

||||||||||||||||||