Lamoral, Count of Egmont

| |||||||||

Read other articles:

2008 song by Agnes On and OnSingle by Agnesfrom the album Dance Love Pop ReleasedAugust 11, 2008Recorded2008GenreDance-popEuropopSynthpopLength3:53 (Original Radio Edit) 3:08 (UK Radio Edit)LabelRoxySongwriter(s)Anders Hansson, Steven DiamondProducer(s)Anders HanssonAgnes singles chronology Champion (2006) On and On (2008) Release Me (2008) Agnes international singles chronology Release Me(2008) On and On(2009) I Need You Now(2009) Agnes UK singles chronology I Need You Now(2009) On and …

Bartholomä Lambang kebesaranLetak Bartholomä NegaraJermanNegara bagianBaden-WürttembergWilayahStuttgartKreisOstalbkreisPemerintahan • MayorThomas KuhnLuas • Total20,75 km2 (801 sq mi)Ketinggian641 m (2,103 ft)Populasi (2021-12-31)[1] • Total2.056 • Kepadatan0,99/km2 (2,6/sq mi)Zona waktuWET/WMPET (UTC+1/+2)Kode pos73566Kode area telepon07173Pelat kendaraanAASitus webwww.bartholomae.de Bartholomä Bartho…

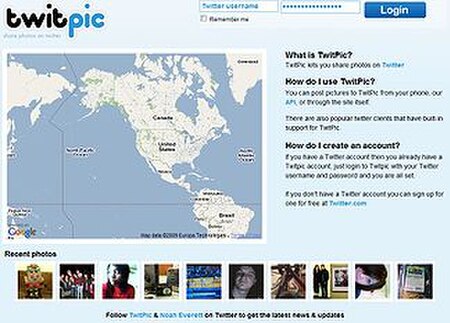

TwitpicCuplikan Twitpic pada November 2009URLhttp://www.twitpic.comTipeBerbagi fotoRegistration (en)DibutuhkanLangueInggrisPemilikNoah EverettPembuatNoah EverettService entry (en)Awal 2008[1]Peringkat Alexa141[2]KeadaanDaring Twitpic adalah sebuah situs web yang memungkinkan pengguna dengan mudah mengirimkan gambar ke layanan mikroblog dan media sosial Twitter.[3] Twitpic sering digunakan oleh jurnalis masyarakat untuk mengunggah dan mendistribusikan gambar pada saat itu …

Mammalian protein found in Homo sapiens HMGCRAvailable structuresPDBOrtholog search: PDBe RCSB List of PDB id codes1DQ8, 1DQ9, 1DQA, 1HW8, 1HW9, 1HWI, 1HWJ, 1HWK, 1HWL, 2Q1L, 2Q6B, 2Q6C, 2R4F, 3BGL, 3CCT, 3CCW, 3CCZ, 3CD0, 3CD5, 3CD7, 3CDA, 3CDBIdentifiersAliasesHMGCR, HMG-CoA reductase, Entrez 3156, LDLCQ3, 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase, Hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA reductaseExternal IDsOMIM: 142910 MGI: 96159 HomoloGene: 30994 GeneCards: HMGCR Gene location (Human)Chr.Chromosome 5 (hum…

Sebuah foto satelit yang terdiri dari pulau-pulau dan daerah kontinental di Eropa Utara. Eropa Utara merupakan sebuah sebutan bagi bagian utara Eropa, meski perbatasannya tidak tetap dan memiliki berbagai versi. Merupakan sebutan yang mengelompokkan negara Nordik (yang ditampilkan dalam semua arti): Denmark, Finlandia, Islandia, Norwegia dan Swedia, juga Åland, Kepulauan Faroe, Jan Mayen dan Svalbard. (Meski secara politik dan sejarah sangat erat dengan Eropa Utara, teritori Nordik Greenland se…

Pour les articles homonymes, voir Banat. Cet article est une ébauche concernant la Serbie et la géographie. Vous pouvez partager vos connaissances en l’améliorant (comment ?) selon les recommandations des projets correspondants. Banat central Administration Pays Serbie Villesou municipalités Novi BečejNova CrnjaŽitišteSečanjZrenjanin Démographie Population 186 851 hab. (2011) Densité 57 hab./km2 Groupes ethniques Serbes, Hongrois Géographie Coordonnées 45° …

Cette page concerne l'année 1177 du calendrier julien. Chronologies Bataille navale entre Chams et Khmers, relief du temple du Bayon.Données clés 1174 1175 1176 1177 1178 1179 1180Décennies :1140 1150 1160 1170 1180 1190 1200Siècles :Xe XIe XIIe XIIIe XIVeMillénaires :-Ier Ier IIe IIIe Chronologies thématiques Religion (,) et * Croisades Science () et Santé et médecine Terrorisme Calendriers Romain Chinois Gré…

Questa voce o sezione deve essere rivista e aggiornata appena possibile. Commento: I dati su produzione, consumi e importazioni sono obsoleti e andrebbero allineati agli outlook più recenti Sembra infatti che questa voce contenga informazioni superate e/o obsolete. Se puoi, contribuisci ad aggiornarla. Questa voce o sezione sugli argomenti chimica e ingegneria è priva o carente di note e riferimenti bibliografici puntuali. Commento: Buona parte dei dati numerici e delle affermazioni più …

Austrian light weapons manufacturer For other uses, see Glock (disambiguation). Glock Ges.m.b.H.Company typePrivate (Ges.m.b.H.)IndustryArms industryFounded1963; 61 years ago (1963)[1]FounderGaston GlockHeadquartersDeutsch-Wagram, Lower Austria, AustriaProductsFirearmsKnivesEntrenching toolsApparelHorse care productsNumber of employees1,325 (2015)[2]Websitewww.glock.com Glock Ges.m.b.H. (doing business as GLOCK) is a light weapons manufacturer headquartered in D…

Хека бог магии Мифология Древнеегипетская Толкование имени магия, «усиление деятельности Ка» Пол мужской Отец Атум или Хнум Мать Менхит Связанные понятия Медицина Древнего Египта Животное змеи Упоминания Тексты Саркофагов Медиафайлы на Викискладе Хека (егип. Ḥk3 �…

此条目序言章节没有充分总结全文内容要点。 (2019年3月21日)请考虑扩充序言,清晰概述条目所有重點。请在条目的讨论页讨论此问题。 哈萨克斯坦總統哈薩克總統旗現任Қасым-Жомарт Кемелұлы Тоқаев卡瑟姆若马尔特·托卡耶夫自2019年3月20日在任任期7年首任努尔苏丹·纳扎尔巴耶夫设立1990年4月24日(哈薩克蘇維埃社會主義共和國總統) 哈萨克斯坦 哈萨克斯坦政府與�…

هذه المقالة يتيمة إذ تصل إليها مقالات أخرى قليلة جدًا. فضلًا، ساعد بإضافة وصلة إليها في مقالات متعلقة بها. (مارس 2016) سوق الموردة بعض المحال القديمة بسوق الموردة شرق سوق الموردة سوق الموردة اقدم هذه الأسواق في أم درمان، عقود مرت على سوق الموردة الذي يرجع تاريخه إلى ما قبل الحكم…

Bandar Udara Internasional Rostov na DonuАэропорт Ростов-на-ДонуIATA: ROVICAO: URRRInformasiJenisKomersialPengelolaJoint Stock Aviation CompanyMelayaniRostov na DonuLokasiRostov na Donu, RusiaMaskapai penghubungDonaviaKetinggian dpl79 mdplKoordinat47°15′30″N 039°49′6″E / 47.25833°N 39.81833°E / 47.25833; 39.81833Koordinat: 47°15′30″N 039°49′6″E / 47.25833°N 39.81833°E / 47.25833; 39.81833Situs w…

For other uses, see Scotland (disambiguation). City in South Dakota, United StatesScotland, South DakotaCityMotto(s): Live, Work, PlayLocation in Bon Homme County and the state of South DakotaCoordinates: 43°08′53″N 97°43′11″W / 43.14806°N 97.71972°W / 43.14806; -97.71972CountryUnited StatesStateSouth DakotaCountyBon HommeIncorporated1885[1]Government • MayorRyan Robb[2]Area[3] • Total0.90 sq mi (2…

Awal The Knight's Tale pada manuskrip Ellesmere. Awal The Wife of Bath's Tale dari manuskrip Ellesmere. Manuskrip Ellesmere yang memuat The Canterbury Tales karangan Geoffrey Chaucer, adalah sebuah naskah manuskrip yang berasal dari abad ke-15. Naskah manuskrip ini sekarang disimpan di Perpustakaan Huntington Library, di San Marino, Kalifornia (MS EL 26 C 9). Selain manuskrip ini, ada sebuah manuskrip awal lainnya yang memuat teks yang sama dan disebut sebagai Manuskrip Hengwrt. Para pakar berpe…

British pro-European weekly 'pop-up' newspaper For other publications, see European (disambiguation). The New EuropeanFront page of issue 154 (from mid-2019)TypeWeekly newspaperFormatCompactPublisherThe New European LtdEditor-in-chiefMatt KellyEditorSteve AngleseyFounded4 July 2016; 7 years ago (2016-07-04)Political alignmentPro-EuropeanismLanguageEnglishHeadquarters22 Highbury Grove, London N5CountryUnited KingdomCirculation33,000 weekly sales (UK)ISSN2398-8762Websitetheneweur…

Activities by the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency in occupied and post-occupation Japan Seal of the Central Intelligence Agency This article is part of a series on theLiberal Democratic Party (Japan) History1950s 1955 System Soviet–Japanese JointDeclaration of 1956 U.S.-Japan Security Treaty 1960s Three Non-Nuclear Principles 1970s Lockheed bribery scandals Treaty of Peace and Friendship between Japan and China 1980s Recruit scandal Japanese asset price bubble 1990s Recruit scandal Lost Decad…

الجدار الرملي المغربي في الصحراء الغربيةمعلومات عامةالبداية عقد 1980 البلد الجمهورية العربية الصحراوية الديمقراطيةالمغربموريتانيا تقع في التقسيم الإداري الصحراء الغربية الأسباب حرب الصحراء الغربية المُطوِّر القوات المسلحة الملكية المغربية الطول 2٬700 كيلومتر[1] — 150 ك�…

Town in British Columbia, Canada Not to be confused with Bella Bella, British Columbia. For other uses, see Bella Coola. Unincorporated community in British Columbia, CanadaBella CoolaUnincorporated communityBella Coola Consumers Co-opBella CoolaCoordinates: 52°22′N 126°45′W / 52.367°N 126.750°W / 52.367; -126.750CountryCanadaProvinceBritish ColumbiaRegional districtCentral CoastPopulation • Total2,163Highways Hwy 20Websitebellacoola.ca Bella Cool…

Organi costituzionali romani Assemblee romane Senato (Senatus) princeps senatus senatus consultum Comizi curiati (comitia curiata) Comizi centuriati (comitia centuriata) Comizi tributi (comitia populi tributa) Comizi calati (comitia calata) Concili della plebe (Concilium plebis) Magistrati ordinari Cursus honorum: censore (censor) console (consul) pretore (praetor) edile (aedilis) questore (quaestor) tribuno della plebe (tribunus plebis) duumviri (duumviri) triumviri (triumviri) seviri (seviri) …