|

Los Alamos Primer

The Los Alamos Primer is a printed version of the first five lectures on the principles of nuclear weapons given to new arrivals at the top-secret Los Alamos laboratory during the Manhattan Project. The five lectures were given by physicist Robert Serber in April 1943. The notes from the lectures which became the Primer were written by Edward Condon. HistoryThe Los Alamos Primer was composed from five lectures given by the physicist Robert Serber to the newcomers at the Los Alamos Laboratory in April 1943, at the start of the Manhattan Project. The aim of the project was to build the first nuclear bomb, and these lectures were a very concise introduction into the principles of nuclear weapon design. Serber was a postdoctoral student of J. Robert Oppenheimer, the leader of the Los Alamos Laboratory, and worked with him on the project from the very start. The five lectures were conducted at April 5, 7, 9, 12, and 14, 1943; according to Serber, between 30 and 50 people attended them. Notes were taken by Edward Condon; the Primer is just 24-pages-long. Only 36 copies were printed at the time.[1] Serber later described the lectures:[1]

In July 1942, Oppenheimer held a "conference" at his office at Berkeley. No records were preserved, but the Primer arose from all the aspects of bomb design discussed there.[1] ContentThe Primer, though only 24-pages-long, consists of 22 sections, divided into chapters:[1]

The first paragraph states the intention of the Los Alamos Laboratory during World War II:[1]

The Primer contained the basic physical principles of nuclear fission, as they were known at the time, and their implications for nuclear weapon design. It suggested a number of possible ways to assemble a critical mass of uranium-235 or plutonium, the most simple being the shooting of a "cylindrical plug" into a sphere of "active material" with a "tamper"—dense material which would reflect neutrons inward and keep the reacting mass together to increase its efficiency (this model, the Primer said, "avoids fancy shapes"). They also explored designs involving spheroids, a primitive form of "implosion" (suggested by Richard C. Tolman), and explored the speculative possibility of "autocatalytic methods" which would increase the efficiency of the bomb as it exploded. According to Rhodes,

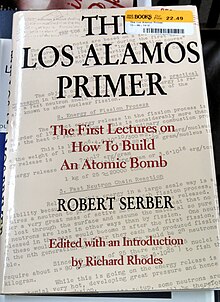

The Primer became designated as the first official Los Alamos technical report (LA-1), and though its information about the physics of fission and weapon design was soon rendered obsolete, it is still considered a fundamental historical document in the history of nuclear weapons. Its contents would be of little use today to someone attempting to build a nuclear weapon, a fact acknowledged by its complete declassification in 1965.[3] In 1992, an edited version of the Primer with many annotations and explanations by Serber was published with an introduction by Richard Rhodes, who previously published The Making of the Atomic Bomb. The 1992 edition also contains the Frisch–Peierls memorandum, written in 1940 in England.[3][4] Reception The physicist Freeman Dyson, who knew Serber, Oppenheimer, and other participants of the Manhattan Project, called the Primer a "legendary document in the literature of nuclear weapons". He praised "Serber's clear thinking", but harshly criticized the Primer's publication, writing "I still wish that it had been allowed to languish in obscurity for another century or two." Acknowledging that it was unclassified in 1965, and that it can't be useful to any bomb designer from 1950, Dyson still thinks that such publication can be dangerous:[3]

Dyson compared bomb-building with LSD synthesis: "Nuclear weapons and LSD are both highly addictive. Both have been manufactured extensively by bright young people seduced by a myth and searching for adventure. Both have destroyed many lives and are likely to destroy many more if the myths are not dispelled. ... Books that present either LSD or nuclear bombs as a romantic adventure can be a danger to public health and safety."[3] His article, titled "Dragon's Teeth", reflects another analogy he uses in his criticisms:[3]

Dyson concludes his review writing: "With luck, this charming little book will be read only by elderly physicists and historians, people who can appreciate its elegance without being seduced by its magic."[3] Other reviews, however, were more favorable. John F. Ahearne writes that the book "remains mathematical", and that it can be useful to young scientists: "the insight to be gained from reading Serber's lucid descriptions of how to analyze complex events by using first approximations. Serber was speaking in many cases to a group of experimentalists who, as one of the experimental group leaders is noted as saying, found "a qualitative argument was more convincing than any amount of fancy theory." A good physicist should be able to get an approximate answer to any complex question using what he or she carries around in the head, the well known "back of the envelope" calculation."[5] Paul W. Henriksen praised the book, writing that "one will be even more impressed with the magnitude of the effort to build an atomic bomb to try to end World War II". He notes that the "annotated version is fascinating in several respects. It is a rare instance in which one of the contributors to a historical event has gone back and explained his work, its importance, and the mistakes that were made at the same time." He also notes that the book is "one of the few books to deal at all with the technical side of the bomb project."[6] Matthew Hersch writes that the book has "power to amaze", and that "The Los Alamos Primer is a work bound to be read differently by different generations ... [it] is a rich text that peers into a moment of innovation that had global consequences."[7] Frank A. Settle also finds the primer to be unique in style and context, and sees it as "a significant contribution to the technical and scientific history of this important period."[4] Publication history

LiteratureArticles

Editions

Original

References

External links

|