Neutrality Acts of the 1930s

|

Nick Rimando Rimando bermain untuk D.C. United pada tahun 2006Informasi pribadiNama lengkap Nicholas Paul Rimando[1]Tanggal lahir 17 Juni 1979 (umur 44)Tempat lahir Montclair, California, Amerika SerikatTinggi 5 ft 9 in (1,75 m)Posisi bermain Penjaga gawangInformasi klubKlub saat ini Real Salt LakeNomor 18Karier junior1997–1999 UCLA BruinsKarier senior*Tahun Tim Tampil (Gol)2000–2001 Miami Fusion 47 (0)2000 → MLS Pro-40 (pinjaman) 2 (0)2002–2006 D.C. United 98…

CraniataRentang fosil: Kambrium Awal - sekarang PreЄ Є O S D C P T J K Pg N Klasifikasi ilmiah Kerajaan: Animalia Filum: Chordata (tanpa takson): CraniataLankester, 1877[1] Subphyla Petromyzontida (lampre) (diperdebatkan) Myxini (remang) Vertebrata Sinonim Craniota Haeckel, 1866 Pachycardia Haeckel, 1866 Craniata atau Craniota adalah suatu klad yang diusulkan untuk mencakup semua Chordata yang termasuk vertebrata (subfilum Vertebrata) dan remang (Myxini) sebagai perwakilan hidupnya. Cr…

Dewan Perwakilan Rakyat Daerah Kabupaten MojokertoDewan Perwakilan RakyatKabupaten Mojokerto2019-2024JenisJenisUnikameral Jangka waktu5 tahunSejarahSesi baru dimulai24 Agustus 2019PimpinanKetuaHj. Ayni Zuroh, S.E., M.M. (PKB) sejak 18 September 2019 Wakil Ketua IHj. Setia Pudji Lestari, S.E., M.Si. (PDI-P) sejak 18 September 2019 Wakil Ketua IIHj. Any Mahnunah, S.E., M.M. (Golkar) sejak 30 Juni 2022 Wakil Ketua IIIH. Mokhammad Sholeh, S.Sos. (Demokrat) sejak 18 September 2019 Kom…

Иное название этого понятия — «Китайцы»; другие значения этого слова см. Китайцы. Население Китая Численность 1,409,670,000 чел Плотность 145 чел/км² Рождаемость 6,39 ‰ Смертность 7,87 ‰ Коэффициент рождаемости ~1,00 Возрастная структура до 14 лет 16,48 % 15–64 года 69,4 % с�…

American politician Rep. Samuel Friedel, 1953 from Congressional Pictorial Directory Samuel Nathaniel Friedel (April 18, 1898 – March 21, 1979), a Democrat, was a U.S. Congressman who represented the 7th congressional district of Maryland from January 3, 1953 to January 3, 1971. Born in Washington, D.C., to Russian-Jewish immigrants,[1] Friedel moved with his family to Baltimore, Maryland, when he was six months old and attended the public schools in Baltimore and Strayer Business Coll…

Questa voce sull'argomento stadi di calcio dell'Ungheria è solo un abbozzo. Contribuisci a migliorarla secondo le convenzioni di Wikipedia. Sóstói Stadion Informazioni generaliStato Ungheria UbicazioneSzékesfehérvár Inizio lavori1963 Inaugurazione1967 Chiusura2015 Demolizione2016 Ristrutturazione2002-2004 Informazioni tecnichePosti a sedere14900 Coperturatribuna centrale Mat. del terrenoerba Dim. del terreno105 × 68 m Uso e beneficiariCalcio Vadásztölténygyári(1967…

Pada tahun 1956, Robert Ludvigovich Bartini mendekati biro desain Beriev dengan proposal untuk kendaraan efek Wing-In-Ground. Be-1 menjadi prototipe eksperimental pertama, yang digunakan untuk menjelajahi stabilitas dan kontrol dari sayap pesawat efek tanah. Pesawat Be-1 menampilkan dua mengapung dengan bagian sayap aspek rasio yang sangat rendah antara mereka dan panel sayap kecil yang normal memperluas luar mengapung. Permukaan hydrofoils piercing yang dipasang di bagian bawah mengapung. Pesaw…

Ancient Egyptian cobra-goddess For the queen, see Meretseger (queen). MeretsegerName in hieroglyphs Major cult centerTheban Necropolis, Deir el-MedinaSymbolCobra snake Meretseger (also known as Mersegrit[1]' or Mertseger) was a Theban cobra-goddess in ancient Egyptian religion,[2] in charge with guarding and protecting the vast Theban Necropolis — on the west bank of the Nile, in front of Thebes — and especially the heavily guarded Valley of the Kings.[3][4]&#…

Place in Borsod-Abaúj-Zemplén, HungaryAlsódobszaChurch, Alsódobsza Coat of armsAlsódobszaLocation of AlsódobszaCoordinates: 48°10′48″N 21°00′06″E / 48.17999°N 21.00178°E / 48.17999; 21.00178Country HungaryCountyBorsod-Abaúj-ZemplénArea • Total10.69 km2 (4.13 sq mi)Population (2015) • Total287 • Density27/km2 (70/sq mi)Time zoneUTC+1 (CET) • Summer (DST)UTC+2 (CEST)Postal code…

Villa in Cannes, once owned by Pablo Picasso This article includes a list of references, related reading, or external links, but its sources remain unclear because it lacks inline citations. Please help improve this article by introducing more precise citations. (January 2016) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) Villa La CaliforniePablo Picasso with René Bernasconi [de; fr]at Villa La Californie in 1955Location within Provence-Alpes-Côte d'AzurFormer namesVilla F�…

Another MePoster rilis teatrikalNama lainTionghoa李茂换太子MandarinLǐ Mào huàn tàizǐ SutradaraGao Ke[1] (高可)PemeranMa LiChang Yuan [zh]Ai Lun [zh]Wei Xiang (魏翔)PerusahaanproduksiNew Classics MediaTanggal rilis 01 Januari 2022 (2022-01-01) NegaraTiongkokBahasaMandarinPendapatankotor$80.8 juta[2] Another Me (Hanzi: 李茂换太子; Pinyin: Lǐ Mào huàn tàizǐ; harfiah: 'Li Mao bertukar dengan putra mahkota'; juga…

Provincia di Leccoprovincia Provincia di Lecco – VedutaVeduta della Valsassina LocalizzazioneStato Italia Regione Lombardia AmministrazioneCapoluogoLecco PresidenteAlessandra Hofmann (centro-destra) dal 19-12-2021 Data di istituzione6 marzo 1992 TerritorioCoordinatedel capoluogo45°51′N 9°24′E / 45.85°N 9.4°E45.85; 9.4 (Provincia di Lecco)Coordinate: 45°51′N 9°24′E / 45.85°N 9.4°E45.85; 9.4 (Provincia di Lecco) Superfici…

State park in Mississippi, United States Wall Doxey State ParkWall Doxey State ParkLocation in MississippiLocationMarshall County, Mississippi, United StatesCoordinates34°39′53″N 89°27′46″W / 34.6647507°N 89.4626949°W / 34.6647507; -89.4626949[1]Area750 acres (300 ha) land; 60 acres (24 ha) water[2]Elevation338 ft (103 m)Established1935Administered byMississippi Department of Wildlife, Fisheries and ParksDesignationMiss…

此條目介紹的是2012年在上海创办的一家民营新闻媒体。关于1946年在上海创刊的一份周刊,请见「观察 (杂志)」。关于2013年在上海创办、原名「上海觀察」的网络应用程序,请见「上觀新聞」。关于“观察者”的其他含义,请见「观察者」。 此條目過於依赖第一手来源。 (2021年1月17日)请補充第二手及第三手來源,以改善这篇条目。 观察者网观察者网首页在2019年7月3�…

Diwata-1 This list covers satellites built and/or operated by entities in the Philippines – by private firms based in the Philippines or by the Philippine government. The first Philippine satellites were operated by private companies. The first Filipino-owned satellite is Agila-1, a satellite acquired in 1996 by Mabuhay Satellite Corporation from PT Pasifik Satelit Nusantara, an Indonesian company. The first Philippine satellite launched to space was Agila-2 which was placed to orbit in 1997. …

New Zealand media business New Zealand Media and EntertainmentCompany typePublicTraded asNZX: NZMIndustryRadio broadcastingPrint mediaE-commercePredecessorAPN New ZealandThe Radio NetworkGrabOneFoundedAuckland, New Zealand (2014; 10 years ago (2014))HeadquartersAuckland, New ZealandNumber of locations25 marketsArea servedNew ZealandKey peopleMichael Raymond Boggs (CEO)[1]Services Print media The New Zealand HeraldBay of Plenty TimesRotorua Daily PostNorthern AdvocateThe…

جزء من سلسلة مقالات حولنظم الحكومات أشكال السلطة انفصالية دولة مرتبطة دومينيون مشيخة محمية فدرالية كونفدرالية تفويض السلطات دولة اتحادية فوق وطنية إمبراطورية الهيمنة دولة مركزية التقسيم الإداري مصدر السلطة ديمقراطية(سلطة الأكثرية) ديمارية مباشرة ليبرالية تمثيلية اجتماع…

This article needs to be updated. The reason given is: this article is largely missing information about this topic from 1991 onward. Please help update this article to reflect recent events or newly available information. (September 2023)Labor unions in JapanNational organization(s)Japanese Trade Union Confederation (Rengo) National Confederation of Trade Unions (Zenroren) National Trade Union Council (Zenrokyo) OthersRegulatory authorityMinistry of Health, Labour and WelfarePrimary legislation…

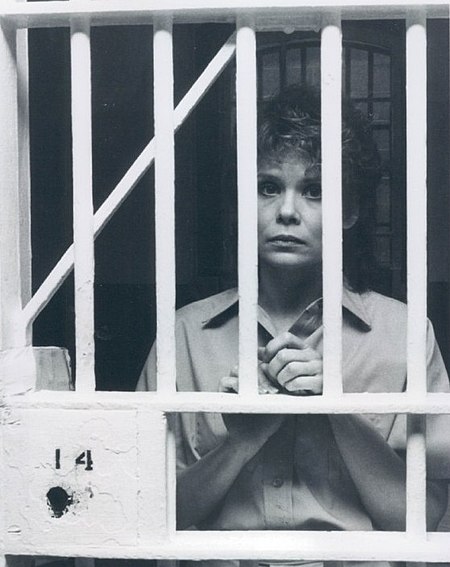

American actress (born 1949) This biography of a living person needs additional citations for verification. Please help by adding reliable sources. Contentious material about living persons that is unsourced or poorly sourced must be removed immediately from the article and its talk page, especially if potentially libelous.Find sources: Julia Barr – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (May 2013) (Learn how and when to remove this message) Julia Ba…

Wife of Julius Caesar (c. 97 – c. 69 BC) This article is about the wife of Julius Caesar. For other uses, see Cornelia (disambiguation). CorneliaCornelia from Promptuarii Iconum Insigniorum, with the inscription cornelia sinnae [filia] c[ai] caes[aris] vx[or], or Cornelia, Cinna's [daughter], G[aius] Caes[ar's] wifeBornc. 97 BCRomeDiedc. 69 BC (aged about 28)RomeKnown forThe first or second wife of Julius CaesarSpouse(s)Julius Caesar (84–69 BC; her death)ChildrenJulia (76–…