|

Rich man and Lazarus

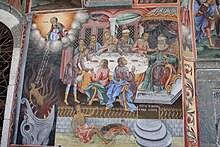

The rich man and Lazarus (also called the parable of Dives and Lazarus)[a] is a parable of Jesus from the 16th chapter of the Gospel of Luke.[6] Speaking to his disciples and some Pharisees, Jesus tells of an unnamed rich man and a beggar named Lazarus. When both die, the rich man goes to Hades and implores Abraham to send Lazarus from his bosom to warn the rich man's family from sharing his fate. Abraham replies, "If they do not listen to Moses and the Prophets, they will not be convinced even if someone rises from the dead." Along with the parables of the Ten Virgins, Prodigal Son, and Good Samaritan, the rich man and Lazarus was one of the most frequently illustrated parables in medieval art,[7] perhaps because of its vivid account of an afterlife. Text

Interpretations There are different views on the historicity and origin of the story of the Rich Man and Lazarus.[8][9] The story is unique to Luke and is not thought to come from the hypothetical Q document.[1] As a literal historical event

St. Jerome and others view the story not as a parable, but as an actual event which was related by Jesus to his followers.[10][11][12] Supporters of this view point to a key detail in the story: the use of a personal name (Lazarus) not found in any other parable. By contrast, in all of the other parables Jesus refers to a central character by a description, such as "a certain man", "a sower", and so forth.[13] As a parable created by JesusOther Christians consider that this is a parable created by Jesus and told to his followers.[14] Tom Wright[15] and Joachim Jeremias[16] both treat it as a "parable". Proponents of this view argue that the story of Lazarus and the rich man has much in common with other stories which are agreed-upon parables, both in language and content (e.g. the reversal of fortunes, the use of antithesis, and concern for the poor). Luther: a parable of the conscienceMartin Luther taught that the story was a parable about rich and poor in this life and the details of the afterlife not to be taken literally:

Lightfoot: a parable against the Pharisees John Lightfoot (1602–1675) treated the parable as a parody of Pharisee belief concerning the Bosom of Abraham, and from the connection of Abraham saying the rich man's family would not believe even if the parable Lazarus was raised, to the priests'[who?] failure to believe in the resurrection of Christ:

E. W. Bullinger in the Companion Bible cited Lightfoot's comment,[19] and expanded it to include coincidence to lack of belief in the resurrection of the historical Lazarus (John 12:10). Bullinger considered that Luke did not identify the passage as a "parable" because it contains a parody of the view of the afterlife:

A parable against the SadduceesThe parable has also been interpreted as a satirical attack on the Sadducees. The Rich Man is identified as the Sadducees on similar lines as Cox, noting the Rich Man's wearing of purple and fine linen, priestly dress[21] and identifying his five brothers as the five sons of Annas.[22] Proponents also note that Abraham's statement that "If they hear not Moses and the prophets, neither will they be persuaded, if one rise from the dead." fits the Sadducees' rejection of the Prophetical books of the Bible as well as their disbelief in a resurrection of the dead.[23][24][25][26] This explanation was popularized in France in the 1860s–1890s by its inclusion in the notes of the pictorial Bible of Abbé Drioux.[27] Perry: a parable of a new covenantAnglican theologian Simon Perry has argued that the Lazarus of the parable (an abbreviated transcript of "Eleazer") refers to Eliezer of Damascus, Abraham's servant. In Genesis 15—a foundational covenant text familiar to any first century Jew—God says to Abraham "this man will not be your heir" (Gen 15:4). Perry argues that this is why Lazarus is outside the gates of Abraham's perceived descendant. By inviting Lazarus to Abraham's bosom, Jesus is redefining the nature of the covenant. It also explains why the rich man assumes Lazarus is Abraham's servant.[28] Friedrich Justus Knecht: a parable of the future lifeThe Catholic German theologian Friedrich Justus Knecht (d. 1921),[29][circular reference] states that this parable gives "a glimpse of the future state, both for our consolation and as a warning." Because after this life there is "a life where everything is quite different from what it is on earth. Lazarus was poor, despised, racked with pain and hunger while he was on earth; but when he died, angels carried his soul to the abode of the just, where he received consolation." However the rich man who when on earth, "led what was apparently a magnificent life. He was esteemed and honoured, surrounded by flatterers, waited on by a host of servants, clad in costly clothes, and he feasted luxuriously every day. But all this magnificence lasted only a short time. He died and was lost for ever, and has been for centuries suffering unspeakable torments."[30] Knecht also reflects on why the rich man was condemned writing: "Because he was a sensual man, an epicurean, and religion was a matter of no consideration with him. His only thought was how to lead a pleasant life, and he neither troubled himself about the future, nor believed in a coming Redeemer. He led a life without prayer, without fear of hell or desire for heaven, a life without grace and without God." Afterlife doctrine The parable teaches in this particular case that both identity and memory remain after death for the soul of the one in a hell.[31] Most Christians believe in the immortality of the soul and particular judgment and see the story as consistent with it, or even refer to it to establish these doctrines as St. Irenaeus, an Early Church father, did.[32] Some Christians believe in the mortality of the soul ("Christian mortalism" or "soul sleep") and general judgment ("Last Judgment") only. This view is held by some Anglicans such as E. W. Bullinger.[33] Proponents of the mortality of the soul, and general judgment, for example Advent Christians, Conditionalists, Seventh-day Adventists, Jehovah's Witnesses, Christadelphians, and Christian Universalists, argue that this is a parable using the framework of Jewish views of the Bosom of Abraham, and is metaphorical, and is not definitive teaching on the intermediate state for several reasons. Nicene creed denominations of Christianity contend, however, that such views had no supporters or traditions supporting the mortality of the soul in the early years of Christianity and only arose after the end of the Middle Ages.[34][35] In Revelation 20:13–14 hades is itself thrown into the "lake of fire" after being emptied of the dead.[36] Literary provenance and legacyJewish sources

Some scholars—e.g., G. B. Caird,[37] Joachim Jeremias,[38] Marshall,[39] Hugo Gressmann,[40]—suggest the basic storyline of The Rich Man and Lazarus was derived from Jewish stories that had developed from an Egyptian folk tale about Si-Osiris.[41][42] Richard Bauckham is less sure,[43] adding:

Steven Cox highlights other elements from Jewish myths that the parable could be mimicking.[45][46] Legacy in Early Christianity and Medieval tradition

Hippolytus of Rome (ca. AD 200) describes Hades with similar details: the bosom of Abraham for the souls of the righteous, fiery torment for the souls of wicked, and a chasm between them.[47] He equates the fires of Hades with the lake of fire described in the Book of Revelation, but specifies that no one will actually be cast into the fire until the end times. In some European countries, the Latin description dives (Latin for "the rich man") is treated as his proper name: Dives. In Italy, the description epulone (Italian for "banquetter") is also used as a proper name. Both descriptions appear together, but not as a proper name, in Peter Chrysologus's sermon De divite epulone (Latin "On the Rich Banquetter"), corresponding to the verse, "There was a rich man who was clothed in purple and fine linen and who feasted sumptuously every day". The story was frequently told in an elaborated form in the medieval period, treating it as factual rather than a parable. Lazarus was venerated as a patron saint of lepers.[48] In the 12th century, crusaders in the Kingdom of Jerusalem founded the Order of Saint Lazarus.  The story was often shown in art, especially carved at the portals of churches, at the foot of which beggars would sit (for example at Moissac and Saint-Sernin, Toulouse), pleading their cause. There is a surviving stained-glass window at Bourges Cathedral.[49] In the Latin liturgy of the Roman Catholic Church, the words of In paradisum are sometimes chanted as the deceased is taken from church to burial, including this supplication: "Chorus angelorum te suscipiat ... et cum Lazaro quondam paupere aeternam habeas requiem" (May the ranks of angels receive you ... and with Lazarus, who was once poor, may you have eternal rest"). Conflation with Lazarus of BethanyThe name "Lazarus" (from the Hebrew: אלעזר, Elʿāzār, Eleazar, "God is my help"[31]) also appears in the Gospel of John, in which Jesus resurrects Lazarus of Bethany four days after his death.[50][51][52] Historically within Christianity, the begging Lazarus of the parable (feast day 21 June) and Lazarus of Bethany (feast day 29 July) have sometimes been conflated,[53] with some churches[clarification needed] celebrating a blessing of dogs, associated with the beggar, on 17 December, date previously associated with Lazarus of Bethany in Roman Catholicism.[54][55] Romanesque iconography carved on portals in Burgundy and Provence might be indicative of such a conflation. For example, at the west portal of the Church of St. Trophime at Arles, the beggar Lazarus is enthroned as St. Lazarus. Similar examples are found at the church at Avallon, the central portal at Vézelay, and the portals of the cathedral of Autun.[56] In literature and poetryGeoffrey Chaucer's Summoner observes that "Dives and Lazarus lived differently, and their rewards were different."[57] In William Shakespeare's Henry IV, Part 1, Sir John Falstaff alludes to the story while insulting his friend Bardolph about his face, comparing it to a memento mori: "I never see thy face," he says "but I think upon hell-fire and Dives that lived in purple; for there he is in his robes, burning, burning" (III, 3, 30–33). When recalling the death of Falstaff in Henry V the description of Lazarus in heaven ("into Abraham's bosom") is parodied as "He's in Arthur's bosom, if ever man went to Arthur's bosom." (II. 3, 7–8) References to Dives and Lazarus are a frequent image in socially conscious fiction of the Victorian period.[58] For example:

Although Dickens' A Christmas Carol and The Chimes do not make any direct reference to the story, the introduction to the Oxford edition of the Christmas Books does.[59] In Herman Melville's Moby-Dick, Ishmael describes a windswept and cold night from the perspective of Lazarus ("Poor Lazarus, chattering his teeth against the curbstone...") and Dives ("...the privilege of making my own summer with my own coals").[60] The poem "The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock" by T. S. Eliot contains the lines: 'To say: "I am Lazarus, come from the dead,/Come back to tell you all, I shall tell you all"' in reference[dubious – discuss] to Dives' request to have Beggar Lazarus return from the dead to tell his brothers of his fate. Richard Crashaw wrote a metaphysical stanza for his Steps to the Temple in 1646 entitled, "Upon Lazarus His Tears":

Dives and Lazarus appear in Edith Sitwell's poem "Still falls the Rain" from "The Canticle of the Rose", first published in 1941. It was written after The Blitz on London in 1940. The poem is dark, full of the disillusions of World War II. It speaks of the failure of man, but also of God's continuing involvement in the world through Christ:[62]

In music

"Vater Abraham, erbarme dich mein", SWV 477 ("Dialogus divites Epulonis cum Abrahamo"), a work by Heinrich Schütz, is a setting of the dialog between Abraham and the rich man dating to the 1620s. It is notable for its virtuosic text-painting of the flames of hell, as well as being an important example of the "dialog" as a step towards the development of the oratorio. "Dives Malus" (the wicked rich man) also known as "Historia Divitis" (c. 1640) by Giacomo Carissimi is a Latin paraphrase of the Luke text, set as an oratorio for 2 sopranos, tenor, bass; for private performance in the oratories of Rome in the 1640s. Mensch, was du tust a German sacred concerto by Johann Philipp Förtsch (1652–1732).[64] The story appeared as an English folk song whose oldest written documentation dates from 1557,[65] with the depiction of the afterlife altered to fit Christian tradition. The song was also published as the Child Ballad Dives and Lazarus in the 19th century.[66] Ralph Vaughan Williams based his orchestral piece Five Variants of Dives and Lazarus (1939) on this folk song,[67] and also used an arrangement as the hymn tune Kingsfold.[68] Benjamin Britten set Edith Sitwell's poem "Still Falls the Rain" (above) to music in his third Canticle in a series of five.[69] The traditional US gospel song "Dip Your Fingers In The Water" has been recorded in various versions by a number of artists, notably by folk singer and civil rights activist Josh White on his 1947 album "Josh White – Ballads And Blues Volume 2".[70] The lyrics contain the recurring refrain "Dip your finger in the water, come and cool my tongue, cause I'm tormented in the flame". Order of Saint Lazarus of JerusalemThe Order of Saint Lazarus of Jerusalem is an order of chivalry that originated in a leper hospital founded by Knights Hospitaller in the 12th century by Crusaders of the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem. The Order of Saint Lazarus is one of the most ancient of the European orders of chivalry, yet is one of the less-known and less-documented orders. The first mention of the Order of Saint Lazarus in surviving sources dates to 1142. The order was originally established to treat the virulent disease of leprosy, its knights originally being lepers themselves.[71] According to the modern-day order's official international website, "From its foundation in the 12th century, the members of the Order were dedicated to two ideals: aid to those suffering from the dreadful disease of leprosy and the defense of the Christian faith."[72] Sufferers of leprosy regarded the beggar Lazarus (of Luke 16:19–31) as their patron saint and usually dedicated their hospices to him.[72] The order was initially founded as a leper hospital outside the city walls of Jerusalem, but hospitals were established all across the Holy Land dependent on the Jerusalem hospital, notably in Acre. It is unknown when the order became militarised, but militarisation occurred before the end of the 12th century due to the large numbers of Templars and Hospitallers sent to the leper hospitals to be treated. The order established 'lazar houses' across Europe to care for lepers, and it was well supported by other military orders, which compelled lazar brethren in their rule to join the Order of Saint Lazarus upon contracting leprosy.[73] See also

ReferencesFootnotes Citations

Further reading

External linksWikimedia Commons has media related to Lazarus and Dives.

|

||||||||||||||||