|

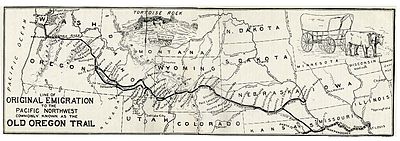

Route of the Oregon Trail

The historic 2,170-mile (3,490 km)[2] Oregon Trail connected various towns along the Missouri River to Oregon's Willamette Valley. It was used during the 19th century by Great Plains pioneers who were seeking fertile land in the West and North. As the trail developed it became marked by numerous cutoffs and shortcuts from Missouri to Oregon. The basic route follows river valleys as grass and water were absolutely necessary. While the first few parties organized and departed from Elm Grove, the Oregon Trail's primary starting point was Independence, Missouri, or Kansas City (Missouri), on the Missouri River. Later, several feeder trails led across Kansas, and some towns became starting points, including Weston, Missouri, Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, Atchison, Kansas, St. Joseph, Missouri, and Omaha, Nebraska. The Oregon Trail's nominal termination point was Oregon City, at the time the proposed capital of the Oregon Territory. However, many settlers branched off or stopped short of this goal and settled at convenient or promising locations along the trail. Commerce with pioneers going further west helped establish these early settlements and launched local economies critical to their prosperity. At dangerous or difficult river crossings, ferries or toll bridges were set up and bad places on the trail were either repaired or bypassed. Several toll roads were constructed. Gradually the trail became easier with the average trip (as recorded in numerous diaries) dropping from about 160 days in 1849 to 140 days 10 years later. Numerous other trails followed the Oregon Trail for much of its length, including the Mormon Trail from Illinois to Utah; the California Trail to the gold fields of California; and the Bozeman Trail to Montana. Because it was more a network of trails than a single trail there were numerous variations, with other trails eventually established on both sides of the Platte, North Platte, Snake, and Columbia rivers. With literally thousands of people and thousands of livestock traveling in a fairly small time slot the travelers had to spread out to find clean water, wood, good campsites, and grass. The dust kicked up by the many travelers was a constant complaint, and where the terrain would allow it there may be between 20 and 50 wagons traveling abreast. Remnants of the trail in Kansas, Nebraska, Wyoming, Idaho, and Oregon have been listed on the National Register of Historic Places, and the entire trail is a designated National Historic Trail (listed as the Oregon National Historic Trail). MissouriInitially, the main "jumping off point" was the common head of the Santa Fe Trail and Oregon Trail—Independence, Missouri/Kansas City, Kansas. Travelers starting in Independence had to ferry across the Missouri River. After following the Santa Fe trail to near present-day Topeka, Kansas, they ferried across the Kansas River to start the trek across Kansas and points west. Another busy "jumping off point" was St. Joseph, Missouri—established in 1843.[3] In its early days, St. Joseph was a bustling outpost and rough frontier town, serving as one of the last supply points before heading over the Missouri River to the frontier. St. Joseph had good steamboat connections to St. Louis, Missouri, and other ports on the combined Ohio, Missouri and Mississippi River systems. During the busy season there were several ferry boats and steamboats available to transport travelers to the Kansas shore where they started their travels westward. Before the Union Pacific Railroad was started in 1865, St. Joseph was the westernmost point in the United States accessible by rail. Other towns used as supply points in Missouri included Old Franklin,[4] Arrow Rock, and Fort Osage. IowaIn 1803 President Thomas Jefferson acquired from France the Louisiana Purchase for fifteen million dollars (equivalent to about $230 million today) which included all the land drained by the Missouri River and roughly doubled the size of U.S. territory. The future states of Iowa and Missouri, located west of the Mississippi River and east of the Missouri River, were part of this purchase. The Lewis and Clark Expedition stopped several times in the future state of Iowa on their 1805-1806 expedition to the west coast. A disputed 1804 treaty between Quashquame and William Henry Harrison (future ninth President of the U.S.) that surrendered much of the future state of Illinois to the U.S. enraged many Sauk (Sac) Indians and led to the 1832 Black Hawk War. As punishment for the uprising, and as part of a larger settlement strategy, treaties were subsequently designed to remove all Indians from Iowa Territory. Some settlers started drifting into Iowa in 1833. President Martin Van Buren on July 4, 1838, signed laws establishing the Territory of Iowa. Iowa was located opposite the junction of the Platte and Missouri rivers and was used by some of the Fur trapper rendezvous traders as a starting point for their supply expeditions. In 1846 the Mormons, expelled from Nauvoo, Illinois, traversed Iowa (on part of the Mormon Trail) and settled temporarily in significant numbers on the Missouri River in Iowa and the future state of Nebraska at their Winter Quarters near the future city of Omaha, Nebraska. (See: Missouri River settlements (1846–1854)[5]) The Mormons established about 50 temporary towns, including the town of Kanesville (renamed Council Bluffs, Iowa in 1852) on the east bank of the Missouri River opposite the mouth of the Platte. For those travelers to Oregon, California, and Utah who were bringing their teams to the Platte River junction, Kanesville and other towns become major "jumping off places" and supply points. In 1847 the Mormons established three ferries across the Missouri River, and others established even more ferries for the spring start on the trail. In the 1850 census there were about 8,000 mostly Mormons tabulated in the large Pottawattamie County, Iowa District 21. (The original Pottawattamie County was subsequently made into five counties and parts of several more.) By 1854 most of the Mormon towns, farms and villages were largely taken over by non-Mormons as they abandoned them or sold them for not much and continued their migration to Utah. After 1846 the towns of Council Bluffs, Iowa, Omaha, Nebraska (est. 1852) and other Missouri River towns became major supply points and "jumping off places" for travelers on the Mormon, California, Oregon and other trails west. Kansas Starting initially in Independence or Kansas City in Missouri, the initial trail followed the Santa Fe Trail into Kansas south of the Wakarusa River. After crossing Mount Oread at Lawrence, the trail crossed the Kansas River by ferry or boats near Topeka, and crossed the Wakarusa and Vermillion rivers by ferries. After the Vermillion River the trail angles northwest to Nebraska paralleling the Little Blue River until reaching the south side of the Platte River. Travel by wagon over the gently rolling Kansas countryside was usually unimpeded except where streams had cut steep banks. There a passage could be made with a lot of shovel work to cut down the banks or the travelers could find an already established crossing. Nebraska The term “Oregon Trail” refers to the historical route that early settlers in the United States used in the 19th century as they moved westward across the country. Those emigrants on the eastern side of the Missouri River in Missouri or Iowa used ferries and steamboats (fitted out for ferry duty) to cross into towns in Nebraska. It is estimated that as many as 650,000 moved west on the Overland Trails, including the Oregon Trail, from the early 1840s through the end of the Civil War. Several towns in Nebraska were used as "jumping off places" with Omaha eventually becoming a favorite after about 1855. Fort Kearny (est. 1848) is about 200 miles (320 km) from the Missouri River, and the trail and its many offshoots nearly all converged close to Fort Kearny as they followed the Platte River west. The army-maintained fort was the first chance on the trail to buy emergency supplies, do repairs, get medical aid, or mail a letter. Those on the north side of the Platte could usually wade the shallow river if they needed to visit the fort.  The Platte River and the North Platte River in the future states of Nebraska and Wyoming typically had many channels and islands and were too shallow, crooked, muddy and unpredictable for travel even by canoe. The Platte as it pursued its braided paths to the Missouri River was "too thin to plow and too thick to drink". While unusable for transport, the Platte River and North Platte River valleys provided an easily passable wagon corridor going almost due west with access to water, grass, buffalo, and buffalo chips for fuel.[6] The trails gradually got rougher as it progressed up the North Platte. There were trails on both sides of the muddy rivers. The Platte was about 1 mile (1.6 km) wide and 2 to 60 inches (5.1 to 152.4 cm) deep. The water was silty and bad tasting but it could be used if no other water was available. Letting it sit in a bucket for an hour or so or stirring in a 1/4 cup of cornmeal allowed most of the silt to settle out. Those traveling south of the Platte crossed the South Platte River with its muddy and treacherous crossings using one of about three ferries (in dry years it could sometimes be forded without a ferry) before continuing up the North Platte River valley to Fort Laramie in present-day Wyoming. After crossing over the South Platte the travelers encountered Ash Hollow with its steep descent down Windlass Hill. In the spring in Nebraska and Wyoming the travelers often encountered fierce wind, rain and lightning storms. Until about 1870 travelers encountered hundreds of thousands of bison migrating through Nebraska on both sides of the Platte River, and most travelers killed several for fresh meat and to build up their supplies of dried jerky for the rest of the journey. The prairie grass in many places was several feet high with only the hat of a traveler on horseback showing as they passed through the prairie grass. In many years the Indians fired much of the dry grass on the prairie every fall so the only trees or bushes available for firewood were on islands in the Platte river. Travelers gathered and ignited dried buffalo chips to cook their meals. These burned fast in a breeze, and it could take two or more bushels of chips to get one meal prepared. Those traveling south of the Platte crossed the South Platte fork at one of about three ferries (in dry years it could be forded without a ferry) before continuing up the North Platte River valley into present-day Wyoming heading to Fort Laramie. Before 1852 those on the north side of the Platte crossed the North Platte to the south side at Fort Laramie. After 1852 they used Child's Cutoff to stay on the north side to about the present day town of Casper, Wyoming, where they crossed over to the south side.[7] Notable landmarks in Nebraska include Courthouse and Jail Rocks, Chimney Rock, Scotts Bluff, and Ash Hollow State Historical Park.[8] Today much of the Oregon Trail follows roughly along Interstate 80 from Wyoming to Grand Island, Nebraska. From there U.S. Highway 30 which follows the Platte River is a better approximate path for those traveling the north side of the Platte. The National Park Service (NPS) gives traveling advice for those who want to follow other branches of the trail.[9] Cholera on the Platte RiverBecause of the Platte's brackish water, the preferred camping spots were along one of the many fresh water streams draining into the Platte or the occasional fresh water spring found along the way. These preferred camping spots became sources of cholera in the epidemic years (1849–1855) as many thousands of people used the same camping spots with essentially no sewage facilities or adequate sewage treatment. There are many cases cited where a person would be alive and apparently healthy in the morning and dead by nightfall. Fort Laramie marked the end of most cholera outbreaks. Spread by cholera bacteria in fecal contaminated water, cholera caused massive diarrhea, leading to dehydration and death. In those days its cause and treatment were unknown, and it was often fatal—up to 30% of infected people died. It is believed that the swifter flowing rivers in Wyoming helped prevent the germs from spreading.[10] The cause of cholera, ingesting the Vibrio cholerae bacterium from contaminated water,[11] and the best treatment for cholera infections were unknown in this era. Literally hundreds of travelers on the combined California, Oregon, and Mormon Trails succumbed to cholera in the 1849-1855 time period. Most were buried in unmarked graves in Kansas, Nebraska, and Wyoming. ColoradoA branch of the Oregon Trail crossed the very northeast corner of Colorado if they followed the South Platte River to one of its last crossings. This branch of the trail passed through present-day Julesburg, Colorado before entering Wyoming. Later settlers to much of what became the state of Colorado followed the Platte and South Platte rivers into their settlements there. WyomingAfter crossing the South Platte River the Oregon Trail follows the North Platte River out of Nebraska into Wyoming. Fort Laramie, at the junction of the Laramie River and the North Platte River, was a major stopping point. Fort Laramie was a former fur trading outpost originally named Fort John that was purchased in 1848 by the U.S. Army to protect travelers on the trails.[12]  After crossing the South Platte the trail continues up the North Platte River, crossing many small swift flowing creeks. As the North Platte veers to the south the trail crosses the North Platte to the Sweetwater River valley which heads almost due west. Independence Rock is located on the Sweetwater River. The Sweetwater would have to be crossed up to nine times before the trail crosses over the Continental Divide at South Pass, Wyoming. From South Pass the trail continues southwest crossing Big Sandy Creek (about 10 feet (3.0 m) wide and 1 foot (0.30 m) deep) before hitting the Green River. Three to five ferries were in use on the Green during peak travel periods. The swift and treacherous Green River, which eventually empties into the Colorado River, was usually at high water in July and August, and it was a dangerous crossing. After crossing the Green the main trail continues on in an approximate southwest direction until it encounters the Blacks Fork of the Green River and Fort Bridger, Wyoming. From Fort Bridger the Mormon Trail continued southwest following the upgraded Hastings Cutoff[13] through the Wasatch Mountains. From Fort Bridger, the main trail, comprising several variants, veered northwest over the Bear River Divide and descended to the Bear River Valley.[14] The trail turned north following the Bear River past the terminus of the Sublette-Greenwood Cutoff at Smiths Fork[15] and on to the Thomas Fork Valley at the present Wyoming-Idaho border. Over time, two major heavily used cutoffs were established in Wyoming. The Sublette-Greenwood Cutoff was established in 1844 and cut about 70 miles (110 km) off the main route. It leaves the main trail about 10 miles (16 km) west of South Pass and heads almost due west crossing Big Sandy Creek and then about 45 miles (72 km) of waterless, very dusty desert before reaching the Green River near the present town of La Barge. Ferries here transferred them across the Green River. From there the Sublette-Greenwood Cutoff trail had to cross a mountain range to connect with the main trail near Cokeville, Wyoming in the Bear River valley.[16] The Lander Road, formally the Fort Kearney, South Pass, and Honey Lake Wagon Road, was established and built by U.S. government contractors in 1858-59.[17] It was about 80 miles (130 km) shorter than the main trail through Fort Bridger with good grass, water, firewood and fishing but it was a much steeper and rougher route, crossing three mountain ranges. In 1859, 13,000[18] of the 19,000[19] emigrants traveling to California and Oregon utilized the Lander Road. The traffic in later years is undocumented. The Lander Road departs the main trail at Burnt Ranch near South Pass, crosses the Continental Divide north of South Pass and reaches the Green River near the present town of Big Piney, Wyoming. From there the trail followed Big Piney Creek west before passing over the 8,800 feet (2,700 m) Thompson Pass in the Wyoming Range. It then crosses over the Smith Fork of the Bear River before ascending and crossing another 8,200 feet (2,500 m) pass on the Salt River Range of mountains and then descending into Star Valley Wyoming. It exited the mountains near the present Smith Fork road about 6 miles (9.7 km) south of the town of Smoot, Wyoming. The road continued almost due north along the present day Wyoming-Idaho western border through Star Valley. To avoid crossing the Salt River (which drains into the Snake River) which runs down Star Valley the Lander Road crossed the river when it was small and stayed west of the Salt River. After traveling down the Salt River valley (Star Valley) about 20 miles (32 km) north the road turned almost due west near the present town of Auburn, Wyoming, and entered into the present state of Idaho along Stump Creek. In Idaho it followed the Stump Creek valley northwest till it crossed the Caribou Mountains and proceeded past the south end of Grays Lake.[20] The trail then proceeded almost due west to meet the main trail at Fort Hall; alternately, a branch trail headed almost due south to meet the main trail near the present town of Soda Springs, Idaho.[21][22] Numerous landmarks are located along the trail in Wyoming including Independence Rock, Ayres Natural Bridge and Register Cliff. UtahIn 1847, Brigham Young and the Mormon pioneers departed from the Oregon Trail at Fort Bridger in Wyoming and followed (and much improved) the rough trail originally recommended by Lansford Hastings to the Donner Party in 1846 through the Wasatch Mountains into Utah.[23] After getting into Utah they immediately started setting up irrigated farms and cities—including Salt Lake City, Utah. In 1848, the Salt Lake Cutoff was established by Sam Hensley,[24] and returning members of the Mormon Battalion providing a path north of the Great Salt Lake from Salt Lake City back to the California and Oregon Trails. This cutoff rejoined the Oregon and California Trails near the City of Rocks near the Utah-Idaho border and could be used by both California and Oregon bound travelers. Located about halfway on both the California and Oregon Trails, many thousands of later travelers used Salt Lake City and other Utah cities as an intermediate stop for selling or trading excess goods or tired livestock for fresh livestock, repairs, supplies or fresh vegetables. The Mormons looked on these travelers as a welcome bonanza as setting up new communities from scratch required nearly everything the travelers could afford to part with. The overall distance to California or Oregon was very close to the same whether one "detoured" to Salt Lake City or not. For their own use and to encourage California- and Oregon-bound travelers, the Mormons improved the Mormon Trail from Fort Bridger and the Salt Lake Cutoff trail. To raise much needed money and facilitate travel on the Salt Lake Cutoff, they set up several ferries across the Weber, Bear and Malad rivers which were used mostly by Oregon- or California-bound travelers. IdahoThe main Oregon and California Trail went almost due north from Fort Bridger to the Little Muddy Creek where it passed over the Bear River Mountains to the Bear River valley which it followed northwest into the Thomas Fork area, where the trail crossed over the present day Wyoming line into Idaho. In the Eastern Sheep Creek Hills in the Thomas Fork valley the emigrants encountered Big Hill. Big Hill was a detour caused by an impassable (then) cut the Bear River made through the mountains and had a tough ascent often requiring doubling up of teams and a very steep and dangerous descent.[25] (Much later, U.S. Highway 30, using modern explosives and equipment, was built through this cut). In 1852 Eliza Ann McAuley found and with help developed the McAuley Cutoff which bypassed much of the difficult climb and descent of Big Hill. About 5 miles (8.0 km) on they passed present day Montpelier, Idaho which is now the site of The National Oregon-California Trail Center.[26] The trail follows the Bear River northwest to present day Soda Springs, Idaho. The soda springs here were a favorite attraction of the pioneers who marveled at the hot carbonated water and chugging "steamboat" springs. Many stopped and did their laundry in the hot water as there was usually plenty of good grass and fresh water available.[27] Just west of Soda Springs the Bear River turns southwest as it heads for The Great Salt Lake and the main trail turns northwest to follow the Portneuf River valley to Fort Hall Idaho. Fort Hall was an old fur trading post located on the Snake River. It was established in 1832 by Nathaniel Jarvis Wyeth and company and later sold in 1837 to the British Hudson's Bay Company. At Fort Hall nearly all travelers were given some aid and supplies if they were available and needed. Mosquitoes were constant pests and travelers often mention that their animals were covered with blood from the bites. The route from Fort Bridger to Fort Hall is about 210 miles (340 km), taking nine to twelve days. At Soda Springs was one branch of Lander Road (established and built with government contractors in 1858) which had gone west from near South Pass, over the Salt River Mountains and down Star Valley before turning west near present-day Auburn, Wyoming and entering Idaho. From there it proceeded northwest into Idaho up Stump Creek canyon for about ten miles (16 km). One branch turned almost 90 degrees and proceeded southwest to Soda Springs. Another branch headed almost due west past Gray’s Lake to rejoin the main trail about 10 miles (16 km) west of Fort Hall. On the main trail about 5 miles (8.0 km) west of Soda Springs Hudspeth's Cutoff (established 1849 and used mostly by California trail users) took off from the main trail heading almost due west, bypassing Fort Hall. It rejoined the California Trail at Cassia Creek near the City of Rocks.[28] Hudspeth's Cutoff had five mountain ranges to cross and took about the same amount of time as the main route to Fort Hall but many took it thinking it was shorter. Its main advantage was that it helped spread out the traffic during peak periods, making more grass available.[29] West of Fort Hall the main trail traveled about 40 miles (64 km) on the south side of the Snake River southwest past American Falls, Massacre Rocks, Register Rock and Coldwater Hill near present-day Pocatello, Idaho. Near the junction of the Raft River and the Snake River, the California Trail diverged from the Oregon Trail at another Parting of the Ways junction. Travellers left the Snake River and followed Raft River about 65 miles (105 km) southwest past present day Almo, Idaho. This trail then passed through the City of Rocks and over Granite Pass where it went southwest along Goose Creek, Little Goose Creek, and Rock Spring Creek. It went about 95 miles (153 km) through Thousand Springs Valley, West Brush Creek, and Willow Creek, before arriving at the Humboldt River in northeastern Nevada near present-day Wells.[30] The California Trail proceeded west down the Humboldt before reaching and crossing the Sierra Nevadas. There are only a few places where the Snake River has not buried itself deep in a canyon. There are few spots where the river slowed down enough to make a crossing possible. Two of these fords were near Fort Hall, where travelers on the Oregon Trail North Side Alternate (established about 1852) and Goodale’s Cutoff (established 1862) crossed the Snake to travel on the north side. Nathaniel Wyeth, the original founder of Fort Hall in 1834, writes in his diary that they found a ford across the Snake River 4 miles (6.4 km) southwest of where he founded Fort Hall. Another possible crossing was a few miles upstream of Salmon Falls where some intrepid travelers floated their wagons and swam their stock across to join the north side trail. Some lost their wagons and teams over the falls.[31] The trails on the north side joined the trail from Three Island Crossing about 17 miles (27 km) west of Glenns Ferry on the north side of the Snake River.[32] (For map of North Side Alternate see:[33]) Goodale's Cutoff, established in 1862 on the north side of the Snake River, formed a spur of the Oregon Trail. This cutoff had been used as a pack trail by Indians and fur traders, and emigrant wagons traversed parts of the eastern section as early as 1852. After crossing the Snake River the 230 miles (370 km) cutoff headed north from Fort Hall toward Big Southern Butte following the Lost River part of the way. It passed near the present-day town of Arco, Idaho and wound through the northern part of Craters of the Moon National Monument. From there it went southwest to Camas Prairie and ended at Old Fort Boise on the Boise River. This journey typically took two to three weeks and was noted for its very rough, lava restricted roads and extremely dry climate, which tended to dry the wooden wheels on the wagons, which caused the iron rims to fall off the wheels. Loss of wheels caused many wagons to be abandoned along the route. It rejoined the main trail east of Boise. Goodale's Cutoff is visible at many points along U.S. Highway 20, U.S. Highway 26 and U.S. Highway 93 between Craters of the Moon National Monument and Carey, Idaho.[34]  From the present site of Pocatello the trail proceeded almost due west on the south side of the Snake River for about 180 miles (290 km). On this route they passed Cauldron Linn rapids, Shoshone Falls, two falls near the present city of Twin Falls, Idaho, and Upper Salmon Falls on the Snake River. At Salmon Falls there were often a hundred or more Indians fishing who would trade for their salmon—a welcome treat. The trail continued west to Three Island Crossing (near present-day Glenns Ferry, Idaho).[35][36] Here most emigrants used the divisions of the river caused by three islands to cross the difficult and swift Snake River by ferry or by driving or sometimes floating their wagons and swimming their teams across. The crossings were doubly treacherous because there were often hidden holes in the river bottom which could overturn the wagon or ensnarl the team, sometimes with fatal consequences. Before ferries were established there were several drownings here nearly every year.[37] The north side of the Snake had better water and grass than the south. The trail from Three Island Crossing to Old Fort Boise was about 130 miles long. The usually lush Boise River valley was a welcome relief. The next crossing of the Snake River was near Old Fort Boise. This last crossing of the Snake could be done on bull boats while swimming the stock across. Others would chain a large string of wagons and teams together. The theory was that the front teams, usually oxen, would get out of water first and with good footing help pull the whole string of wagons and teams across. How well this worked in practice is not stated. Often young Indian boys were hired to drive and ride the stock across the river—they knew how to swim, unlike many pioneers. Today's Idaho Interstate 84 roughly follows the Oregon Trail till it leaves the Snake River near Burley, Idaho. From there Interstate 86 to Pocatello roughly approximates the trail. Highway 30 roughly follows the path of the Oregon Trail from there to Montpelier, Idaho. Starting in about 1848 the South Alternate of Oregon Trail (also called the Snake River Cutoff) was developed as a spur off the main trail. It bypassed the Three Island Crossing and continued traveling down the south side of the Snake River. It rejoined the trail near present-day Ontario, Oregon. It hugged the southern edge of the Snake River canyon and was a much rougher trail with poorer water and grass, requiring occasional steep descents and ascents with the animals down into the Snake River canyon to get water. Travellers on this route avoided two dangerous crossings of the Snake River.[38] Today's Idaho State Route 78 roughly follows the path of the South Alternate route of the Oregon Trail. In 1869 the Central Pacific established Kelton, Utah as a railhead and the terminus of the western mail was moved from Salt Lake City. The Kelton Road became important as a communication and transportation road to the Boise Basin.[39] OregonOnce across the Snake River ford near Old Fort Boise the weary travelers traveled across what would become the state of Oregon. The trail then went to the Malheur River and then past Farewell Bend on the Snake River, up the Burnt River canyon and northwest to the La Grande valley before coming to the Blue Mountains. In 1843 settlers cut a wagon road over these mountains making them passable for the first time to wagons. The trail went to the Whitman Mission near Fort Nez Perce in Washington until 1847 when the Whitmans were killed by Native Americans. At Fort Nez Perce some built rafts or hired boats and started down the Columbia; others continued west in their wagons until they reached The Dalles. After 1847 the trail bypassed the closed mission and headed almost due west to present day Pendleton, Oregon, crossing the Umatilla River, John Day River, and Deschutes River before arriving at The Dalles. Interstate 84 in Oregon roughly follows the original Oregon Trail from Idaho to The Dalles. Arriving at the Columbia at The Dalles and stopped by the Cascade Mountains and Mount Hood, some gave up their wagons or disassembled them and put them on boats or rafts for a trip down the Columbia River. Once they transited the Cascade's Columbia River Gorge with its multiple rapids and treacherous winds they would have to make the 1.6 miles (2.6 km) portage around the Cascade Rapids before coming out near the Willamette River where Oregon City, Oregon was located. The pioneer's livestock could be driven around Mount Hood on the narrow, crooked and rough Lolo Pass. Several Oregon Trail branches and route variations led to the Willamette Valley. The most popular was the Barlow Road, which was carved through the forest around Mount Hood from The Dalles in 1846 as a toll road at $5.00 per wagon and 10 cents per head of livestock. It was rough and steep with poor grass but still cheaper and safer than floating goods, wagons and family down the dangerous Columbia River. In Central Oregon there was the Santiam Wagon Road (established 1861), which roughly parallels Oregon Highway 20 to the Willamette Valley. The Applegate Trail (established 1846) cutting off the California Trail from the Humboldt River in Nevada crossed part of California before cutting north to the south end of the Willamette Valley. Originally U.S. Route 99 (later renamed to Oregon Route 99) and Interstate 5 through Oregon roughly follow the original Applegate Trail. References

|