|

The Holocaust in Estonia

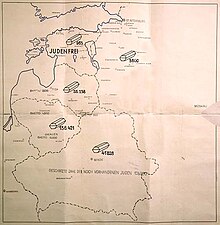

The Holocaust in Estonia refers to Nazi crimes during the occupation of Estonia by Nazi Germany. By the end of 1941 virtually all of the 950 to 1,000 Estonian Jews unable to escape Estonia before its Nazi occupation (25% of the total prewar Jewish population) were killed by German units such as Einsatzgruppe A and/or local collaborators. The Romani people in Estonia were also killed or enslaved by Nazi occupiers and their collaborators.[1] The occupation authorities also killed around 6,000 ethnic Estonians and 1,000 ethnic Russians in Estonia, often claiming that they were Communists or Communist sympathizers, a categorization that also included relatives of alleged Communists. In addition around 15,000 Soviet prisoners-of-war and Jews from other parts of Europe were killed in Estonia during the German occupation.[2] Before the HolocaustPrior to World War II, Jewish life flourished in Estonia with more cultural autonomy than any other Jewish community in all of Europe.[citation needed] The local Jewish population had full control of education and other aspects of cultural life.[3] In 1936, the British-based Jewish newspaper The Jewish Chronicle reported that "Estonia is the only country in Eastern Europe where ... Jews are left in peace and are allowed to lead a free and unmolested life and fashion it in accord with their national and cultural principles."[4] Murders of JewsRound-ups and killings of the remaining Jews began immediately; the first stage of Generalplan Ost required the "removal" of 50% of Estonians.[5]: 54 The killings were undertaken by the extermination squad Einsatzkommando 1A (Sonderkommando) under Martin Sandberger, part of Einsatzgruppe A led by Walter Stahlecker, following the arrival of the first German troops on July 7, 1941. Arrests and executions continued as the Germans, with the assistance of local collaborators, advanced through Estonia, which became part of the Reichskommissariat Ostland. The Sicherheitspolizei (Security Police) was established for internal security under Ain-Ervin Mere in 1942. Estonia was declared Judenfrei quite early by the German occupation regime, at the Wannsee Conference.[6] The Jews who remained in Estonia (929 according to the most recent calculation[7][unreliable source?]) were murdered.[8] Fewer than a dozen Estonian Jews are known to have survived the war in Estonia.[7]  German policy toward the Jews in EstoniaThe Estonian state archives contain death certificates and lists of Jews executed dated July, August, and early September 1941. For example, the official death certificate of Rubin Teitelbaum, born in Tapa on January 17, 1907, states laconically in a form with item 7 already printed with only the date left blank: "7. By a decision of the Sicherheitspolizei on September 4, 1941, condemned to death, with the decision being carried out the same day in Tallinn." Teitelbaum's crime was "being a Jew" and thus constituting a "threat to the public order". On September 11, 1941 an article entitled "Juuditäht seljal" – "A Jewish Star on the Back" appeared in the Estonian mass-circulation newspaper Postimees. It stated that Otto-Heinrich Drechsler, the High Commissioner of Ostland, had issued ordinances requiring all Jewish residents of Ostland from that day on to wear a visible yellow six-pointed Star of David at least 10 cm (4 in). in diameter on the left side of their chest and back. On the same day regulations[9] issued by the Sicherheitspolizei were delivered to all local police departments proclaiming that the Nuremberg Laws were in force in Ostland, defining who is a Jew, and what Jews could and could not do. Jews were prohibited from changing their place of residence, walking on the sidewalk, using any means of transportation, going to theatres, museums, cinema, or school. The professions of lawyer, physician, notary, banker, or real estate agent were declared closed to Jews, as was the occupation of street hawker. The regulations also declared that the property and homes of Jewish residents would be confiscated. The regulations emphasized that work to this end was to begin as soon as possible, and that police were to compiley lists of Jews, their addresses, and their property by September 20, 1941. The regulations also provided for the establishment of a concentration camp near the south-eastern Estonian city of Tartu. A later decision provided for the construction of a Jewish ghetto near the town of Harku, but this was never built. A small concentration camp was built there instead. The national archives contain material pertinent to the cases of about 450 Estonian Jews. They were typically arrested at home or in the street, taken to the local police station, and charged with the 'crime' of being Jews. They were either shot outright or sent to concentration camps and shot later. An Estonian woman, described the arrest of her Jewish husband:[10]

Foreign JewsThe Nazis intended mass genocide after the German invasion of Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia. Jews from countries outside the Baltics were deported there to be killed.[11] An estimated 10,000 Jews were killed in Estonia after having been deported to camps there from elsewhere in eastern Europe.[citation needed] The Nazi regime established 22 Nazi concentration camps in occupied Estonian territory for foreign Jews, where they were slave labor. The largest, Vaivara concentration camp, served as a transit camp and processed 20,000 Jews from Latvia and the Lithuanian ghettos.[citation needed] Usually able-bodied men were selected to work in the oil shale mines in northeastern Estonia. Women, children, and old people were killed on arrival. At least two trainloads of Central European Jews were deported to Estonia and were killed on arrival at the Kalevi-Liiva site near Jägala concentration camp.[6] Murder of foreign Jews at Kalevi-LiivaAccording to testimony of the survivors, at least two transports with about 2,100–2,150 Central European Jews,[12] arrived at the railway station at Raasiku, one from Theresienstadt (Terezin) with Czechoslovakian Jews and one from Berlin with German citizens. Around 1,700–1,750 people were immediately taken to an execution site at the Kalevi-Liiva sand dunes and shot.[12] About 450 people were selected for work at the Jägala concentration camp.[12][13] Transport Be 1.9.1942 from Theresienstadt arrived at the Raasiku station on September 5, 1942, after a five-day trip.[14][15] According to testimony given to Soviet authorities by Ralf Gerrets, one of the accused at the 1961 war crimes trials in USSR, eight busloads of Estonian auxiliary police had arrived from Tallinn.[15] The selection process was supervised by Ain-Ervin Mere, chief of Security Police in Estonia; those transportees not selected for slave labor were sent by bus to a killing site near the camp. Later the police,[15] in teams of 6 to 8 men,[12] killed the Jews by machine gun fire. During later investigations, however, some guards of camp denied the participation of police and said that executions were done by camp personnel.[12] On the first day, a total of 900 people were murdered in this way.[12][15] Gerrets testifies that he had fired a pistol at a victim who was still making noises in the pile of bodies.[15][16] The whole operation was directed by SS commanders Heinrich Bergmann and Julius Geese.[12][15] Few witnesses pointed out Heinrich Bergmann as the key figure behind the extermination of Estonian gypsies. In the case of Be 1.9.1942, the only ones chosen for labor and to survive the war were a small group of young women who were taken through a series of concentration camps in Estonia, Poland and Germany to Bergen-Belsen, where they were liberated.[17] Camp commandant Laak used the women as sex slaves, killing many after they had outlived their usefulness.[13][18] A number of foreign witnesses were heard at the post-war trials in Soviet-occupied Estonia, including five women who had been transported on Be 1.9.1942 from Theresienstadt.[15]

Romani people

A few witnesses pointed out Heinrich Bergmann as the key figure behind the extermination of Estonian Roma people.[17] Estonian collaborationUnits of the Eesti Omakaitse (Estonian Home Guard; approximately 1000 to 1200 men) were directly involved in criminal acts, taking part in the round-up of 200 Roma people and 950 Jews.[2] The final acts of liquidating the camps, such as Klooga, which involved the mass-shooting of roughly 2,000 prisoners, was facilitated by members of the 287th Police Battalion.[2] Survivors report that, during these last days before liberation, when Jewish slave labourers were visible, the Estonian population in part attempted to help the Jews by providing food and other types of assistance.[2][20] War crimes trialsFour Estonians deemed most responsible for the murders at Kalevi-Liiva were accused at the war crimes trials in 1961. Two were later executed, while the Soviet occupation authorities were unable to press charges against the other two due to the fact that they lived in exile.[21] There have been 7 known ethnic Estonians (Ralf Gerrets, Ain-Ervin Mere, Jaan Viik, Juhan Jüriste, Karl Linnas, Aleksander Laak and Ervin Viks) who have faced trials for crimes against humanity committed during the Nazi occupation in Estonia. The accused were charged with murdering up to 5,000 German and Czechoslovakian Jews and Romani people near the Kalevi-Liiva concentration camp in 1942–1943. Ain-Ervin Mere, commander of the Estonian Security Police (Group B of the Sicherheitspolizei) under the Estonian Self-Administration, was tried in absentia. Before the trial, Mere had been an active member of the Estonian community in England, contributing to Estonian-language publications.[22] At the time of the trial, however, he was being held in custody in England, having been accused of murder. He was never deported[23] and died a free man in England in 1969. Ralf Gerrets, the deputy commandant at the Jägala camp. Jaan Viik, (Jan Wijk, Ian Viik), a guard at the Jägala labor camp, out of the hundreds of Estonian camp guards and police, was singled out for prosecution due to his particular brutality.[19] Witnesses testified that he would throw small children into the air and shoot them. He did not deny the charge.[16] A fourth accused, camp commandant Aleksander Laak (Alexander Laak), was discovered living in Canada, but committed suicide before he could be brought to trial. In January 1962, another trial was held in Tartu. Juhan Jüriste, Karl Linnas and Ervin Viks were accused of murdering 12,000 civilians in the Tartu concentration camp. Number of victimsSoviet-Estonian era sources estimate the total number of Soviet citizens and foreigners to be murdered in Nazi-occupied Estonian Soviet Socialist Republic to be 125,000.[24][25][26][27][28] The bulk of this number consists Jews from Central and Western Europe and Soviet prisoners-of-war killed or starved to death in prisoner-of-war camps on Estonian territory.[27][28] The Estonian History Commission estimates the total number of victims to be roughly 35,000, consisting of the following groups:[2]

The number of Estonian Jews killed is less than 1,000; the German Holocaust perpetrators Martin Sandberger and Walter Stahlecker cite the numbers 921 and 963 respectively. In 1994 Evgenia Goorin-Loov calculated the exact number to be 929.[7] Modern memorials  Since the reestablishment of the Estonian independence, markers were put in place for the 60th anniversary of the mass executions that were carried out at the Lagedi, Vaivara and Klooga (Kalevi-Liiva) camps in September 1944.[29] On February 5, 1945 in Berlin, Ain Mere founded the Eesti Vabadusliit together with SS-Obersturmbannführer Harald Riipalu.[30] He was sentenced to the capital punishment during the Holocaust trials in Soviet Estonia but was not extradited by Great Britain and died there in peace. In 2002 the Government of the Republic of Estonia decided to officially commemorate the Holocaust. In the same year, the Simon Wiesenthal Center had provided the Estonian government with information on alleged Estonian war criminals, all former members of the 36th Estonian Police Battalion. In August 2018 it was reported that the memorial at Kalevi-Liiva was defaced.[31] Concentration campsKZ-StammlagerKZ-Außenlager

Arbeits- und Erziehungslager

PrisonsOther concentration camps

See alsoReferences

Bibliography

Further reading

External links |