|

Tricuspid valve

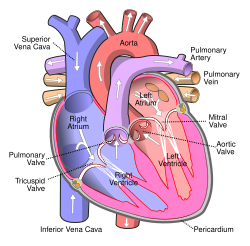

The tricuspid valve, or right atrioventricular valve, is on the right dorsal side of the mammalian heart, at the superior portion of the right ventricle. The function of the valve is to allow blood to flow from the right atrium to the right ventricle during diastole, and to close to prevent backflow (regurgitation) from the right ventricle into the right atrium during right ventricular contraction (systole). StructureThe tricuspid valve usually has three cusps or leaflets, named the anterior, posterior, and septal cusps.[1] Each leaflet is connected via chordae tendineae to the anterior, posterior, and septal papillary muscles of the right ventricle, respectively. Tricuspid valves may also occur with two or four leaflets; the number may change over a lifetime.[2] FunctionThe tricuspid valve functions as a one-way valve that closes during ventricular systole to prevent regurgitation of blood from the right ventricle back into the right atrium. It opens during ventricular diastole, allowing blood to flow from the right atrium into the right ventricle. The back flow of blood is also known as regression or tricuspid regurgitation. Tricuspid regurgitation can result in increased ventricular preload because the blood refluxed back into the atrium is added to the volume of blood that must be pumped back into the ventricle during the next cycle of ventricular diastole. Increased right ventricular preload over a prolonged period of time may lead to right ventricular enlargement (dilatation),[3] which can progress to right heart failure if left uncorrected.[4] Clinical significanceInfected valves can result in endocarditis in intravenous drug users.[5][6] Patients who inject narcotics or other drugs intravenously may introduce infection, which can travel to the right side of the heart, most often caused by the bacteria S. aureus.[7] In patients without a history of intravenous exposure, endocarditis is more frequently left-sided.[7] The tricuspid valve can be affected by rheumatic fever, which can cause tricuspid stenosis or tricuspid regurgitation.[8] Some individuals are born with congenital abnormalities of the tricuspid valve. Congenital apical displacement of the tricuspid valve is called Ebstein's anomaly and typically causes significant tricuspid regurgitation. Certain carcinoid syndromes can affect the tricuspid valve by producing fibrosis due to serotonin production by those tumors. The first endovascular tricuspid valve implant was performed by surgeons at the Cleveland Clinic.[9] Tricuspid regurgitationTricuspid regurgitation is common and is estimated to occur in 65–85% of the population.[10] In the Framingham Heart Study presence of any severity of tricuspid regurgitation, ranging from trace to above moderate was in 82% of men and in 85.7% of women.[11] Mild tricuspid regurgitation tends to be common, benign, and in structurally normal tricuspid valve apparatus can be considered a normal variant.[10] Moderate or severe tricuspid regurgitation is usually associated with tricuspid valve leaflet abnormalities and/or possibly annular dilation and is usually pathologic which can lead to irreversible damage of cardiac muscle and worse outcomes due to chronic prolonged right ventricular volume overload.[10] Additional images

See alsoReferences

External links

|

||||||||||||||||||||||