Crack epidemic in the United States

|

Artikel ini bukan mengenai lempar lembing. Ilustrasi seseorang yang berusaha melempar seekor kambing Lempar kambing (dalam bahasa Spanyol: Lanzamiento de cabra desde campanario atau Salto de la cabra) adalah sebuah festival di Manganeses de la Polvorosa, provinsi Zamora, Spanyol. Festival ini dirayakan pada hari Minggu keempat bulan Januari. Dalam festival ini sekelompok pemuda akan melemparkan seekor kambing hidup dari atap sebuah gereja. Kerumunan di bawah kemudian akan mencoba menangkap kambi…

Artikel ini membahas variasi makanan khas Tiongkok yang dinamakan Bakcang. Untuk bacang spesies tumbuhan, silakan lihat Bacang. BacangBeberapa bacang yang diikat dengan benangNama lainZongzi, bak-cang, bah-cang, nyukcung / ngiug-zung, cung-e / zung-eJenisKue beras, kue ketanTempat asalTiongkokDaerahberbagai daerah di Tiongkok, daerah beretnis TionghoaDibuat olehBangsa TionghoaBahan utamaBeras ketan diisi dengan isian berbeda dan dibungkus dengan daun bambu atau daun pandan.Hidangan serupaMont ph…

Madison Cawthorn David Madison Cawthorn (lahir 1 Agustus 1995) adalah seorang politikus asal Amerika Serikat. Sebagai anggota Partai Republik, Cawthorn menjadi anggota DPR setelah memenangkan pemilu 2020.[1] Ia adalah anggota termuda di Kongres sejak Jed Johnson Jr. dan anggota Kongres pertama yang lahir pada 1990an.[2] Referensi ^ North Carolina Election Results: 11th Congressional District. The New York Times (dalam bahasa Inggris). ISSN 0362-4331. Diarsipkan dari versi as…

Artikel ini sebatang kara, artinya tidak ada artikel lain yang memiliki pranala balik ke halaman ini.Bantulah menambah pranala ke artikel ini dari artikel yang berhubungan atau coba peralatan pencari pranala.Tag ini diberikan pada Desember 2023. Herman Allositandi adalah hakim pada Pengadilan Negeri Jakarta Selatan yang ditangkap oleh Tim Pemberantasan Tindak Pidana Korupsi pada tanggal 9 Januari 2006 karena melakukan pemerasan terhadap saksi kasus korupsi PT Jamsostek.[1] Pada tanggal 2…

Berikut ini merupakan daftar anggota Konstituante Republik Indonesia yang terpilih dalam pemilihan umum legislatif Indonesia 1955, diurutkan berdasarkan partainya. Mereka bersidang pertama kali pada tanggal 4 Maret 1956 dan dibubarkan pada 5 Juli 1959 menyusul berlakunya Dekret Presiden 5 Juli 1959. 1-99 No. Nama Partai Mulai menjabat Selesai menjabat Fungsional Tahun lahir Domisili 5 Sutan Amiruddin, AnwarAnwar Sutan Amiruddin Persatuan Tharikah Islam 17 Januari 1959 5 Juli 1959 1920 Maninjau 3…

Часть серии статей о Холокосте Идеология и политика Расовая гигиена · Расовый антисемитизм · Нацистская расовая политика · Нюрнбергские расовые законы Шоа Лагеря смерти Белжец · Дахау · Майданек · Малый Тростенец · Маутхаузен · …

Pertunjukan tari Saman di sekitar candi Borobudur. Tari Saman merupakan salah satu media untuk menyampaikan pesan atau dakwah. Tarian ini mencerminkan pendidikan, keagamaan, sopan santun, kepahlawanan, kekompakan dan kebersamaan. Sebelum saman dimulai yaitu sebagai mukaddimah atau pembukaan, tampil seorang tua cerdik pandai atau pemuka adat untuk mewakili masyarakat setempat (keketar) atau nasihat-nasihat yang berguna kepada para pemain dan penonton. Lagu dan syair pengungkapannya secara bersama…

Radio station in Limpopo, South Africa Capricorn FMBroadcast areaLimpopoFrequency96.0 MHz (Mokopane/Polokwane)98.0 MHz (Hoedspruit)105.4 MHz (Louis Trichardt)97.6 MHz (Tzaneen)ProgrammingFormatUrbanHistoryFounded2007First air date26 November 2007 (2007-11-26)LinksWebcastWindows Media AudioWebsitecapricornfm.co.za Capricorn FM is a commercial radio station in the Limpopo province of South Africa.[1] Overview The Capricorn FM station broadcasts in the FM range and also strea…

Panji LarasGenre Drama Laga Sejarah Epos Misteri PembuatMD EntertainmentDitulis olehAviv ElhamSkenarioAviv ElhamSutradaraEdi S. JonatanPemeran Rey Bong Rama Michael Ryana Dea Puadin Redi Tatiana Sivek Ria Irawan Penggubah lagu temaMahir's BandLagu pembukaSang Anak Langit — Mahir's BandLagu penutupSang Anak Langit — Mahir's BandNegara asalIndonesiaBahasa asliBahasa IndonesiaJmlh. musim1Jmlh. episode19 (daftar episode)ProduksiProduser Dhamoo Punjabi Manoj Punjabi Pengaturan kameraMulti-kameraD…

Catholic society of apostolic life This article relies excessively on references to primary sources. Please improve this article by adding secondary or tertiary sources. Find sources: Priestly Fraternity of Saint Peter – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (September 2023) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) Priestly Fraternity of Saint PeterFraternitas Sacerdotalis Sancti PetriAbbreviationFSSPFormationJuly 18, 1988; …

Cet article est une ébauche concernant un homme politique français. Vous pouvez partager vos connaissances en l’améliorant (comment ?) selon les recommandations des projets correspondants. Joannis FerrouillatFonctionsDéputé françaisSénateur de la Troisième RépubliqueBiographieNaissance 4 mai 1820LyonDécès 24 mars 1903 (à 82 ans)MontpellierSépulture Cimetière de LoyasseNationalité françaiseActivité Homme politiquemodifier - modifier le code - modifier Wikidata Joannis…

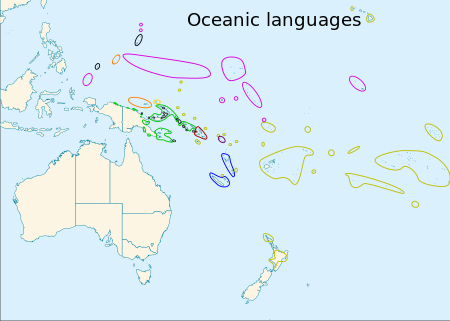

Linkage of Oceanic languages Western OceanicGeographicdistributionWestern PacificLinguistic classificationAustronesianMalayo-PolynesianOceanicWestern OceanicProto-languageProto-Western OceanicSubdivisions North New Guinea linkage Meso-Melanesian linkage Papuan Tip linkage Glottologwest2818 Western Oceanic The Western Oceanic languages is a linkage of Oceanic languages, proposed and studied by Ross (1988). They make up a majority of the Austronesian languages spoken in New Guinea. Clas…

Ancient Egyptian funerary texts Papyrus with hieratic, part of Egypt's Books of Breathing, probably from Thebes. Dated to 323–30 BC (Ptolemaic Kingdom). Currently on display at Germany's Neues Museum. The Books of Breathing (Arabic: كتاب التنفس Kitāb al-Tanafus) are several ancient Egyptian funerary texts, intended to enable deceased people to continue existing in the afterlife. The earliest known copy dates to circa 350 BC.[1] Other copies come from the Ptolemaic Kingdom an…

Philippe Noiret Philippe Noiret (1 Oktober 1930-23 November 2006) merupakan seorang aktor berkebangsaan Prancis. Dia dilahirkan di Lille. Dia berkarier di dunia film sejak tahun 1949 hingga 2006. Dia meninggal dunia pada usia 76 tahun karena kanker. Filmografi Judul Tahun Catatan Gigi 1949 Olivia 1950 Agence matrimoniale 1952 La Pointe courte 1956 Also known as The Short Point, with Agnès Varda Zazie dans le métro 1960 Also known as Zazie in the Metro or Zazie, directed by Louis Malle Le Capit…

Season of television series Psycho-Pass 3Key visual of the series Anime television seriesDirected byNaoyoshi ShiotaniProduced byAkitoshi MoriFumi MorihiroTaka YoshizawaWritten byTow UbukataMakoto FukamiRyō YoshigamiMusic byYugo KannoStudioProduction I.GLicensed byPrime Video (streaming)Original networkFuji TV (Noitamina)Original run October 24, 2019 – December 12, 2019Episodes8 MangaWritten bySaru HashinoPublished byShueishaMagazineShōnen Jump+DemographicSh…

Anglo-French artist, architectural draughtsman, and writer on medieval architecture Not to be confused with his son Augustus Pugin. This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed.Find sources: Augustus Charles Pugin – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (December 2010) (Learn how and when to remove this template mes…

American actor (1882–1957) This article includes a list of references, related reading, or external links, but its sources remain unclear because it lacks inline citations. Please help improve this article by introducing more precise citations. (March 2013) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) Erville AldersonAlderson in Sally of the Sawdust (1925)Born(1882-09-11)September 11, 1882Kansas City, Missouri, U.S.DiedAugust 4, 1957(1957-08-04) (aged 74)Glendale, California, U.S.…

Lukas 6Lukas 6:4-16 pada Papirus 4, yang ditulis sekitar tahun 150-175 M.KitabInjil LukasKategoriInjilBagian Alkitab KristenPerjanjian BaruUrutan dalamKitab Kristen3← pasal 5 pasal 7 → Lukas 6 (disingkat Luk 6) adalah bagian Injil Lukas pada Perjanjian Baru dalam Alkitab Kristen. Disusun oleh Lukas, seorang Kristen yang merupakan teman seperjalanan Rasul Paulus.[1][2] Teks Naskah aslinya ditulis dalam bahasa Yunani. Sejumlah naskah tertua yang memuat salinan pasal ini…

International border Map of Guinea, with Mali to the north-east The Guinea–Mali border is 1,062 km (660 m) in length and runs from the tripoint with Senegal in the north to the tripoint with Ivory Coast in the south.[1] Description The border begins in the north at the tripoint with Senegal on the Balinko river, and then follows this river southwards, before turning to the south-east, utilising various rivers and overland sections.[2] The border then reaches the Bafing Riv…

Questa voce sugli argomenti calciatori tunisini e calciatori francesi è solo un abbozzo. Contribuisci a migliorarla secondo le convenzioni di Wikipedia. Segui i suggerimenti dei progetti di riferimento 1, 2. Yan Valery Nazionalità Francia Tunisia (dal 2023) Altezza 180 cm Peso 85 kg Calcio Ruolo Difensore Squadra Angers Carriera Giovanili 2009-2013 Champigny FC 942013-2015 Rennes2015-2018 Southampton Squadre di club1 2018-2021 Southampton37 (2)2021→ …