Ecocentrism

|

Read other articles:

Universitas Kepausan UrbanianaPontificia Università Urbanianabahasa Latin: Pontificia Universitas UrbanianaMotobahasa Latin: Euntes docetePergi dan mengajar (Matius 28:19)JenisUniversitas Kepausan SwastaDidirikan1 Agustus 1627(397 tahun yang lalu)AfiliasiKatolik (Kongregasi bagi Penginjilan)KanselirKardinal Fernando FiloniRektorAlberto Trevisiol, I.M.C.Staf akademikTeologi, Filsafat, Hukum Kanon, MisiologiLokasiVia Urbano VIII, 16Roma, Italia41°53′58″N 12°27′35″E / &#x…

LandoAwal masa jabatanJuli/Agustus 913Masa jabatan berakhirFebruari/Maret 914PendahuluAnastasius IIIPenerusYohanes XInformasi pribadiNama lahirLandoLahirtanggal tidak diketahuiSabina, ItaliaWafatFebruari/Maret 914Roma, Italia Paus Lando, nama lahir Lando (???-Februari/Maret 914), adalah Paus Gereja Katolik Roma sejak Juli/Agustus 913 hingga Februari/Maret 914. Didahului oleh:Anastasius III Paus913 – 914 Diteruskan oleh:Yohanes X lbs Paus Gereja Katolik Daftar paus grafik masa jabatan oran…

Pemilihan Umum Wali kota Cirebon 20132008201824 Februari 2013Kandidat Calon Drs. Ano Sutrisno, M.M. H. Bamunas S. Boediman, MBA. Partai Partai Golongan Karya PDI-P Suara rakyat 27.232 23.891 Persentase 38% 34% Peta persebaran suara Peta lokasi Kota Cirebon Wali kota dan Wakil Wali kota petahanaSubardi, S.Pd. dan H. Sunaryo H.W.,S.Ip.,M.M. PDI-P Wali kota dan Wakil Wali kota terpilih Drs. H. Ano Sutrisno, M.M. dan Drs. Nasrudin Azis, S.H. Partai Golongan Karya Pemilihan umum Wali kota…

Artikel ini tidak memiliki referensi atau sumber tepercaya sehingga isinya tidak bisa dipastikan. Tolong bantu perbaiki artikel ini dengan menambahkan referensi yang layak. Tulisan tanpa sumber dapat dipertanyakan dan dihapus sewaktu-waktu.Cari sumber: Gunung Kelimutu – berita · surat kabar · buku · cendekiawan · JSTOR Gunung KelimutuDanau Kelimutu di Gunung kelimutuTitik tertinggiKetinggian1.639 m (5.377 kaki)Masuk dalam daftarRibuKoordinat8°46′08″S…

107th (Ulster) Independent Infantry Brigade Signal Squadron302 Signal Squadron85 Signal SquadronCap badge of the Royal Corps of SignalsActive1947–19671967–2009Country United KingdomBranch British ArmyTypeMilitary communications unitSizeSquadronPart of40th (Ulster) Signal RegimentSquadron HQBelfastNickname(s)The Ulster SignallersCorpsRoyal Corps of SignalsInsigniaTactical Recognition FlashMilitary unit 85 (Ulster) Signal Squadron was a military communications unit of the Britis…

Notable American football play Miracle in MotownFord Field, the site of the game. Green Bay Packers (7–4) Detroit Lions (4–7) 27 23 Head coach:Mike McCarthy Head coach:Jim Caldwell 1234 Total GB 001413 27 DET 17033 23 DateDecember 3, 2015StadiumFord Field, Detroit, MichiganRefereeCarl CheffersTV in the United StatesNetworkCBS, NFL NetworkAnnouncersJim Nantz, Phil Simms, Tracy Wolfson The Miracle in Motown was the final play of an American football game between the NFC North divisional rivals…

2000 single by Kylie Minogue For other songs, see On a Night Like This (Bob Dylan song) and On a Night like This (Trick Pony song). On a Night Like ThisSingle by Kylie Minoguefrom the album Light Years B-sideOcean BlueReleased11 September 2000 (2000-09-11)StudioDreamhouse (London, England)Genre Europop dance-pop house Length3:32Label Mushroom Parlophone Songwriter(s) Steve Torch Graham Stack Mark Taylor Brian Rawling Producer(s) Graham Stack Mark Taylor Kylie Minogue singles chron…

Naoto Kan菅 直人Potret resmi, 2009 Perdana Menteri JepangMasa jabatan7 Juni 2010 – 2 September 2011Penguasa monarkiAkihitoPendahuluYukio HatoyamaPenggantiYoshihiko NodaMenteri KeuanganMasa jabatan6 Januari 2010 – 8 Juni 2010Perdana MenteriYukio HatoyamaPendahuluHirohisa FujiiPenggantiYoshihiko NodaDeputi Perdana Menteri JepangMasa jabatan16 September 2009 – 8 Juni 2010Perdana MenteriYukio HatoyamaPendahuluKosonglast held by Wataru Kubo on 11 January 1996Pengga…

New York football team Hudson Valley FortFounded2015Folded2016LeagueFall Experimental Football League (2015–2016)Team historyHudson Valley Fort (2015–2016)Based inFishkill, New YorkStadiumDutchess StadiumColorsLight Blue, Black, Silver, White OwnerFall Experimental Football LeagueHudson Valley RenegadesHead coachJohn JenkinsGeneral managerJohn JenkinsChampionships0Conference titles0Division titles0Playoff berths0 The Hudson Valley Fort was a team in the Fall Experim…

Lambang kotamadya Untuk kegunaan lain, lihat Ha. Hå adalah sebuah kotamadya di provinsi Rogaland, Norwegia. Desa-desa utamanya ialah Nærbø, Varhaug dan Vigrestad, yang berhubungan dengan 3 kotamadya sebelumnya yang bergabung menjadi Hå. Dalam politik setempat, pembagian antara ketiga bekas kotamadya itu amat terlihat. Nama Kotamadya ini dinamai menurut pertanian kuno Hå (Norse Háar). Arti nama itu tidak diketahui. Lambang Lambangnya berasal dari masa modern (1991). Pantai berpasir di Ogna,…

East Timor between 1999 and 2002 East TimorTimor-Leste (Portuguese)Timor Lorosa'e (Tetum) تيمور الشرقية (Arabic)东帝汶 (Chinese)Timor oriental (French)Восточный Тимор (Russian)Timor oriental (Spanish)1999–2002 Flag Coat of arms Location of East Timor at the end of the Indonesian archipelago.StatusUnited Nations protectorateCapitalDiliCommon languagesTetumPortugueseIndonesianEnglishTransitionalAdministrator • 1999–2002 Sérgio Vieira de Mello…

Not to be confused with Milford, Connecticut. Town in Connecticut, United StatesNew Milford, Connecticut WeantinockTownTown of New MilfordThe United Bank Building, located in the Center Historic District FlagSealMotto: Gateway to Litchfield County[1] Litchfield County and Connecticut Western Connecticut Planning Region and ConnecticutShow New MilfordShow ConnecticutShow the United StatesCoordinates: 41°34′37″N 73°24′30″W / 41.57694°N 73.40833°W&…

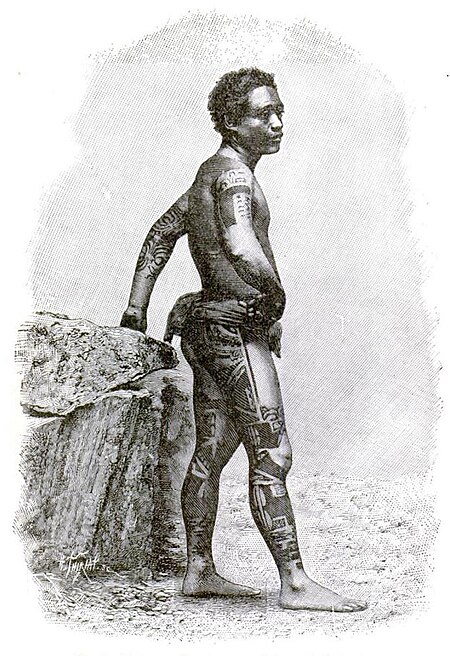

Marquesans performing a Haka dance The Marquesas Islands were colonized by seafaring Polynesians as early as 300 AD, thought to originate from Tonga and the Samoan Islands. The dense population was concentrated in the narrow valleys and consisted of warring tribes. Much of Polynesia, including the original settlers of Hawaii, Tahiti, Rapa Iti and Easter Island, was settled by Marquesans, believed to have departed from the Marquesas as a result more frequently of overpopulation and drought-relate…

Le informazioni riportate non sono consigli medici e potrebbero non essere accurate. I contenuti hanno solo fine illustrativo e non sostituiscono il parere medico: leggi le avvertenze. Il metodo dell'ovulazione Billings (MOB) è un metodo naturale di regolazione della fertilità, usato dalle donne - anche se è consigliato l'aiuto del partner - per monitorare la propria fertilità, identificando i giorni fertili e quelli infertili durante ogni ciclo mestruale. Tabella di riferimento. Indice 1 Me…

Untuk kabupaten dengan nama sama, lihat Kabupaten Alor. AlorPeta lokasi AlorKoordinat8°15′S 124°45′E / 8.250°S 124.750°E / -8.250; 124.750NegaraIndonesiaGugus kepulauanSunda kecilProvinsiNusa Tenggara TimurKabupatenAlorLuas2.119,7 km²Populasi- Alor adalah sebuah pulau yang terletak di ujung timur Kepulauan Nusa Tenggara. Luas wilayahnya 2.119 km², dan titik tertingginya 1.839 m. Pulau ini dibatasi oleh Laut Flores dan Laut Banda di sebelah utara, Selat…

هذه المقالة عن المجموعة العرقية الأتراك وليس عن من يحملون جنسية الجمهورية التركية أتراكTürkler (بالتركية) التعداد الكليالتعداد 70~83 مليون نسمةمناطق الوجود المميزةالبلد القائمة ... تركياألمانياسورياالعراقبلغارياالولايات المتحدةفرنساالمملكة المتحدةهولنداالنمساأسترالياب…

Maurizio IConte di OldenburgStemma In carica1167 –1209 PredecessoreCristiano I SuccessoreCristiano II Nascita1150 Morte1209 DinastiaCasato degli Oldenburg PadreCristiano I MadreCunegonda di Versfleth ConsorteSalomè di Hochstaden-Wickrath FigliCristiano II di OldenburgOttone I di OldenburgEdvige di OldenburgOda di OldenburgCunegonda di OldenburgSalomè di Oldenburg ReligioneCattolicesimo Maurizio I (1150 – 1209) fu conte di Oldenburg dal 1167 al 1209. Indice 1 Biografia 2 Famiglia…

Statue in Trinity Church Square, London Statue of Alfred the GreatPictured in 200951°29′56″N 0°05′37″W / 51.49889°N 0.09361°W / 51.49889; -0.09361LocationSouthwarkMaterialCoade stone and Bath stone Listed Building – Grade IIOfficial nameStatue in Centre of Trinity Church SquareDesignated2 March 1950Reference no.1385998[1] The statue of Alfred the Great in Southwark is thought to be London's oldest outdoor statue. The lower portion comes from a R…

Just ListenAlbum mini karya YounhaDirilis2 Mei 2013Direkam2013GenreRock, pop rockBahasaKoreaLabelWealive/CJ E&M MusicKronologi Younha Supersonic(2012)Supersonic2012 Just Listen(2013) Subsonic(2013)Subsonic2013 Just Listen adalah album mini kedua dari penyanyi asal Korea Selatan Younha.[1] Daftar lagu Daftar lagu dan kredit yang terungkap secara daring pada hari rilis .[2] No.JudulLirikMusikDurasi1.Just Listen (featuring Skull)Younha, SkullScore, Skull3:402.FireworksYounha…

Artikel ini sebatang kara, artinya tidak ada artikel lain yang memiliki pranala balik ke halaman ini.Bantulah menambah pranala ke artikel ini dari artikel yang berhubungan atau coba peralatan pencari pranala.Tag ini diberikan pada Januari 2023. Kekerasan di Kejuaraan Eropa UEFA 2016 meliputi peristiwa hooliganisme sepak bola seperti kerusuhan antarpendukung tim sepak bola di dalam maupun luar stadion selama Kejuaraan Eropa UEFA 2016 berlangsung di Prancis. Peristiwa yang paling disoroti adalah k…