|

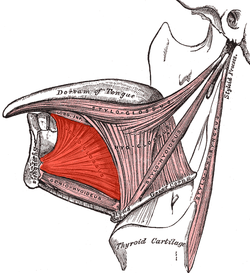

Genioglossus

The genioglossus is one of the paired extrinsic muscles of the tongue. It is a fan-shaped muscle that comprises the bulk of the body of the tongue. It arises from the mental spine of the mandible; it inserts onto the hyoid bone, and the bottom of the tongue. It is innervated by the hypoglossal nerve (cranial nerve XII). The genioglossus is the major muscle responsible for protruding (or sticking out) the tongue. StructureGenioglossus is the fan-shaped extrinsic tongue muscle that forms the majority of the body of the tongue. The muscle is paired, having a left and right portion, which are divided at the midline of the tongue by a septum made of connective tissue.[1] OriginThe large part of the muscle arises from the mental spine of the mandible,[2][3] but some fibers originate directly from the hyoid bone and connect vertically to the tongue.[1] InsertionIts insertions are the hyoid bone and the bottom of the tongue.[2][3] InnervationThe genioglossus is innervated by the hypoglossal nerve,[2] as are all muscles of the tongue except for the palatoglossus.[4] Blood supplyBlood is supplied to the sublingual branch of the lingual artery, a branch of the external carotid artery.[2][1] FunctionThe left and right genioglossus muscles protrude the tongue (anteriorly, out of the mouth) and deviate it towards the opposite side. When acting together, the muscles protrude the tongue directly forward and depress the center of the tongue at its back.[2] Clinical significanceContraction of the genioglossus stabilizes and enlarges the portion of the upper airway that is most vulnerable to collapse. Relaxation of the genioglossus and geniohyoideus muscles, especially during REM sleep, is implicated in obstructive sleep apnea.[5] Given this connection, the mandible can be pulled forward to maximise the airway space, and prevent the tongue from sinking backwards under anaesthesia and obstructing the airway.[2] The genioglossus is often used as a proxy to test the function of the hypoglossal nerve (CN XII), by asking a patient to stick out their tongue. Peripheral damage to the hypoglossal nerve can result in deviation of the tongue to the damaged side. If the tongue protrudes directly forward instead of deviating to either side, then the hypoglossal nerves are likely not injured.[1] HistoryThe name derives from the Greek words γένειον (geneion) meaning "chin", and γλῶσσα (glōssa) meaning "tongue." The earliest recorded mention is by Helkiah Crooke in the early seventeenth century.[6] Other animalsThe canine genioglossus muscle has been divided into horizontal and oblique compartments.[7] References

External links

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||