|

History of Latin America

The term Latin America originated in the 1830s, primarily through Michel Chevalier, who proposed the region could ally with "Latin Europe" against other European cultures. It primarily refers to the Spanish- and Portuguese-speaking countries in the New World. Before the arrival of Europeans in the late 15th and early 16th centuries, the region was home to many indigenous peoples, including advanced civilizations, most notably from South: the Olmec, Maya, Muisca, Aztecs and Inca. The region came under control of the kingdoms of Spain and Portugal, which established colonies, and imposed Roman Catholicism and their languages. Both brought African slaves to their colonies as laborers, exploiting large, settled societies and their resources. The Spanish Crown regulated immigration, allowing only Christians to travel to the New World. The colonization process led to significant native population declines due to disease, forced labor, and violence. They imposed their culture, destroying native codices and artwork. Colonial-era religion played a crucial role in everyday life, with the Spanish Crown ensuring religious purity and aggressively prosecuting perceived deviations like witchcraft. In the early nineteenth century nearly all of areas of Spanish America attained independence by armed struggle, with the exceptions of Cuba and Puerto Rico. Brazil, which had become a monarchy separate from Portugal, became a republic in the late nineteenth century. Political independence from European monarchies did not result in the abolition of black slavery in the new nations, it resulted in political and economic instability in Spanish America, immediately after independence. Great Britain and the United States exercised significant influence in the post-independence era, resulting in a form of neo-colonialism, where political sovereignty remained in place, but foreign powers exercised considerable power in the economic sphere. Newly independent nations faced domestic and interstate conflicts, struggling with economic instability and social inequality. The 20th century brought U.S. intervention and the Cold War's impact on the region, with revolutions in countries like Cuba influencing Latin American politics. The late 20th and early 21st centuries saw shifts towards left-wing governments, followed by conservative resurgences, and a recent resurgence of left-wing politics in several countries. Origin of the term and definitionThe idea that a part of the Americas has a cultural or racial affinity with all Romance cultures can be traced back to the 1830s, in particular in the writing of the French Saint-Simonian Michel Chevalier, who postulated that this part of the Americas were inhabited by people of a "Latin race," and that it could, therefore, ally itself with "Latin Europe" in a struggle with "Teutonic Europe," "Anglo-Saxon America" and "Slavic Europe."[1] The idea was later taken up by Latin American intellectuals and political leaders of the mid- and late-nineteenth century, who no longer looked to Spain or Portugal as cultural models, but rather to France.[2] The actual term "Latin America" was coined in France under Napoleon III and played a role in his campaign to imply cultural kinship with France, transform France into a cultural and political leader of the area and install Maximilian as emperor of Mexico.[3] In the mid-twentieth century, especially in the United States, there was a trend to occasionally classify all of the territory south of the United States as "Latin America," especially when the discussion focused on its contemporary political and economic relations to the rest of the world, rather than solely on its cultural aspects.[4] Concurrently, there has been a move to avoid this oversimplification by talking about "Latin America and the Caribbean," as in the United Nations geoscheme. Since, the concept and definitions of Latin American are very modern, going back only to the nineteenth century, it is anachronistic to talk about "a history of Latin America" before the arrival of the Europeans. Nevertheless, the many and varied cultures that did exist in the pre-Columbian period had a strong and direct influence on the societies that emerged as a result of the conquest, and therefore, they cannot be overlooked. They are introduced in the next section. The Pre-Columbian periodWhat is now Latin America has been populated for millennia, possibly as long as 30,000 years. There are many models of the peopling of the Americas. Precise dating of early civilizations is difficult because there are few text sources. However, highly developed civilizations flourished at various places, such as in the Andes and Mesoamerica. The earliest known human settlement in the area was identified at Monte Verde in southern Chile. Its occupation dates to some 14,000 years ago and there is disputed evidence of even earlier occupation. Over the course of millennia, people spread to all parts of the North and South America and the Caribbean islands. Although the region now known as Latin America stretches from northern Mexico to Tierra del Fuego, the diversity of its geography, topography, climate, and cultivable land means that populations were not evenly distributed. Sedentary populations of fixed settlements supported by agriculture gave rise to complex civilizations in Mesoamerica (central and southern Mexico and Central America) and the highland Andes populations of Quechua and Aymara, as well as Chibcha. Agricultural surpluses from intensive cultivation of maize in Mesoamerica and potatoes and hardy grains in the Andes were able to support distant populations beyond farmers' households and communities. Surpluses allowed the creation of social, political, religious, and military hierarchies, urbanization with stable village settlements and major cities, specialization of craft work, and the transfer of products via tribute and trade. In the Andes, llamas were domesticated and used to transport goods; Mesoamerica had no large domesticated animals to aid human labor or provide meat. Mesoamerican civilizations developed systems of writing; in the Andes, knotted quipus emerged as a system of accounting. The Caribbean region had sedentary populations settled by Arawak or Tainos and in what is now Brazil, many Tupian peoples lived in fixed settlements. Semi-sedentary populations had agriculture and settled villages, but soil exhaustion required relocation of settlements. Populations were less dense and social and political hierarchies less institutionalized. Non-sedentary peoples lived in small bands, with low population density and without agriculture. They lived in harsh environments. By the first millennium CE, the Western Hemisphere was the home of tens of millions of people; the exact numbers are a source of ongoing research and controversy.[5] The last two great civilizations, the Aztecs and Incas, emerged into prominence in the early fourteenth century and mid-fifteenth centuries. Although the Indigenous empires were conquered by Europeans, the sub-imperial organization of the densely populated regions remained in place. The presence or absence of Indigenous populations had an impact on how European imperialism played out in the Americas. The pre-Columbian civilizations of Mesoamerica and the highland Andes became sources of pride for American-born Spaniards in the late colonial era and for nationalists in the post-independence era.[6] For some modern Latin American nation-states, the Indigenous roots of national identity are expressed in the ideology of indigenismo. These modern constructions of national identity usually critique their colonial past.[7] Sport in Pre-Columbian PeriodAs a result of imperialism and colonialism, historians note the diffusion of sports that brought football, baseball, boxing, cricket, and basketball from the empires to its colonies. In the context of Latin America, historians can acknowledge the power imbalances between the colonial elite and those of poorer circumstance by looking at sport history. For instance, dating back to the pre-columbian Mesoamerica, horsemanship contests were an integral part of leisure activity for the individuals of the colonies. However, many colonial official took advantage of their power over the poor people's accessibility to the game by preventing the poorer individuals from accessing the horses. This attempt to control and manipulate the people of the colony failed as many of the indigenous people needed the horses for labor– labor that would serve to benefit the upper class who exploit the colony. Furthermore, horses played an important role in the early day of Latin American sport. Such examples include the horsemanship contests mentioned above, the charreada of Mexico, other equestrian activities in the region that would eventually be Argentina and Uruguay, etc. These sport gave the indigenous people the opportunity to practice values of talent, honor, and teamwork. It also was accessible to the poorer indigenous individuals of the colony because horses were affordable and not relatively expensive to the people of a lower class than those colonial elite.[8] Colonial EraChristopher Columbus landed in the Americas in 1492. Subsequently, the major sea powers in Europe sent expeditions to the New World to build trade networks and colonies and to convert the native peoples to Christianity. Spain concentrated on building its empire on the central and southern parts of the Americas allotted to it by the Treaty of Tordesillas, because of presence of large, settled societies like the Aztec, the Inca, the Maya and the Muisca, whose human and material resources it could exploit, and large concentrations of silver and gold. The Portuguese built their empire in Brazil, which fell in their sphere of influence owing to the Treaty of Tordesillas, by developing the land for sugar production since there was a lack of a large, complex society or mineral resources. During the European colonization of the western hemisphere, most of the native population died, mainly by disease. In what has come to be known as the Columbian exchange, diseases such as smallpox and measles decimated populations with no immunity. The size of the indigenous populations has been studied in the modern era by historians,[9][10][11] but Dominican friar Bartolomé de las Casas raised the alarm in the earliest days of Spanish settlement in the Caribbean in his A Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies. The conquerors and colonists of Latin America also had a major impact on the population of Latin America. The Spanish conquistadors committed savage acts of violence against the natives. According to Bartolomé de las Casas, the Europeans worked the native population to death, separated the men and the women so they could not reproduce, and hunted down and killed any natives who escaped with dogs. Las Casas claimed that the Spaniards made the natives work day and night in mines and would "test the sharpness of their blades"[12] on the natives. Las Casas estimated that around three million natives died from war, slavery, and overworking. When talking about the cruelty, Las Casas said "Who in future generations will believe this? I myself writing it as a knowledgeable eyewitness can hardly believe it." Because the Spanish were now in power, native culture and religion were forbidden. The Spanish even went as far as burning the Maya Codices (like books). These codices contained information about astrology, religion, Gods, and rituals. There are four codices known to exist today; these are the Dresden Codex, Paris Codex, Madrid Codex, and HI Codex.[13] The Spanish also melted down countless pieces of golden artwork so they could bring the gold back to Spain and destroyed countless pieces of art. Colonial-era religion

The Spanish Crown regulated immigration to its overseas colonies, with travelers required to register with the House of Trade in Seville. Since the crown wished to exclude anyone who was non-Christian (Jews, crypto-Jews, and Muslims) passing as Christian, travelers' backgrounds were vetted. The ability to regulate the flow of people enabled the Spanish Crown to keep a grip on the religious purity of its overseas empire. The Spanish Crown was rigorous in their attempt to allow only Christians passage to the New World and required proof of religion by way of personal testimonies. Specific examples of individuals dealing with the Crown allow for an understanding of how religion affected passage into the New World. Francisca de Figueroa, an African-Iberian woman seeking entrance into the Americas, petitioned the Spanish Crown in 1600 in order to gain a license to sail to Cartagena.[14] On her behalf she had a witness attest to her religious purity, Elvira de Medina wrote, "this witness knows that she and parents and her grandparents have been and are Old Christians and of unsullied cast and lineage. They are not of Moorish or Jewish caste or of those recently converted to Our Holy Catholic Faith."[15] Despite Francisca's race, she was allowed entrance into the Americas in 1601 when a 'Decree from His Majesty' was presented, it read, "My presidents and official judges of the Case de Contraction of Seville. I order you to allow passage to the Province of Cartagena for Francisca de Figueroa ..."[16] This example points to the importance of religion, when attempting to travel to the Americas during colonial times. Individuals had to work within the guidelines of Christianity in order to appeal to the Crown and be granted access to travel.

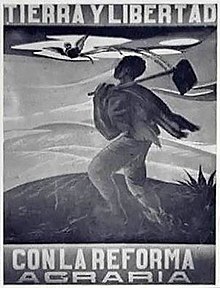

Once in the New World, religion was still a prevalent issue which had to be considered in everyday life. Many of the laws were based on religious beliefs and traditions and often these laws clashed with the many other cultures throughout colonial Latin America. One of the central clashes was between African and Iberian cultures; this difference in culture resulted in the aggressive prosecution of witches, both African and Iberian, throughout Latin America. According to European tradition "[a] witch – a bruja – was thought to reject God and the sacraments and instead worship the devil and observe the witches' Sabbath."[17] This rejection of God was seen as an abomination and was not tolerated by the authorities either in Spain nor Latin America. A specific example, the trial of Paula de Eguiluz, shows how an appeal to Christianity can help to lessen punishment even in the case of a witch trial. Paula de Eguiluz was a woman of African descent who was born in Santo Domingo and grew up as a slave, sometime in her youth she learned the trade of witches and was publicly known to be a sorceress. "In 1623, Paula was accused of witchcraft (brujeria), divination and apostasy (declarations contrary to Church doctrine)."[18] Paula was tried in 1624 and began her hearings without much knowledge of the Crowns way of conducting legal proceedings. There needed to be appeals to Christianity and announcements of faith if an individual hoped to lessen the sentence. Learning quickly, Paula correctly "recited the Lord's Prayer, the Creed, the Salve Regina, and the Ten Commandments" before the second hearing of her trial. Finally, in the third hearing of the trial Paula ended her testimony by "ask[ing] Our Lord to forgive [me] for these dreadful sins and errors and requests ... a merciful punishment."[19] The appeals to Christianity and profession of faith allowed Paula to return to her previous life as a slave with minimal punishment. The Spanish Crown placed a high importance on the preservation of Christianity in Latin America. Nineteenth-century revolutions: the postcolonial era Following the model of the American and French revolutions, most of Latin America achieved its independence by 1825. Independence destroyed the old common market that existed under the Spanish Empire after the Bourbon Reforms and created an increased dependence on the financial investment provided by nations, which had already begun to industrialize; therefore, Western European powers, in particular Great Britain and France, and the United States began to play major roles, since the region became economically dependent on these nations. Independence also created a new, self-consciously "Latin American" ruling class and intelligentsia, which at times avoided Spanish and Portuguese models in their quest to reshape their societies. This elite looked towards other Catholic European models—in particular France—for a new Latin American culture, but did not seek input from indigenous peoples. The failed efforts in Spanish America to keep together most of the initial large states that emerged from independence— Gran Colombia, the Federal Republic of Central America[20] and the United Provinces of South America—resulted a number of domestic and interstate conflicts, which plagued the new countries. Brazil, in contrast to its Hispanic neighbors, remained a united monarchy and avoided the problem of civil and interstate wars. Domestic wars were often fights between federalists and centrists, who ended up asserting themselves through the military repression of their opponents at the expense of civilian political life. The new nations inherited the cultural diversity of the colonial era and strived to create a new identity based around the shared European (Spanish or Portuguese) language and culture. Within each country, however, there were cultural and class divisions that created tension and hurt national unity. For the next few decades there was a long process to create a sense of nationality. Most of the new national borders were created around the often centuries-old audiencia jurisdictions or the Bourbon intendancies, which had become areas of political identity. In many areas the borders were unstable, since the new states fought wars with each other to gain access to resources, especially in the second half of the nineteenth century. The more important conflicts were the Paraguayan War (1864–70; also known as the War of the Triple Alliance) and the War of the Pacific (1879–84). The Paraguayan War pitted Argentina, Brazil and Uruguay against Paraguay, which was utterly defeated. As a result, Paraguay suffered a demographic collapse: the population went from an estimated 525,000 persons in 1864 to 221,000 in 1871 and out of this last population, only around 28,000 were men. In the War of the Pacific, Chile defeated the combined forces of Bolivia and Peru. Chile gained control of saltpeter-rich areas, previously controlled by Peru and Bolivia, and Bolivia became a land-locked nation. By mid-century the region also confronted a growing United States, seeking to expand on the North American continent and extend its influence in the hemisphere. In Mexican–American War (1846–48), Mexico lost over half of its territory to the United States. In the 1860s France attempted to indirectly control Mexico. In South America, Brazil consolidated its control of large swaths of the Amazon Basin at the expense of its neighbors. In the 1880s the United States implemented an aggressive policy to defend and expand its political and economic interests in all of Latin America, which culminated in the creation of the Pan-American Conference, the successful completion of the Panama Canal and the United States intervention in the final Cuban war of independence. The export of natural resources provided the basis of most Latin American economies in the nineteenth century, which allowed for the development of wealthy elite. The restructuring of colonial economic and political realities resulted in a sizable gap between rich and poor, with landed elites controlling the vast majority of land and resources. In Brazil, for instance, by 1910 85% of the land belonged to 1% of the population. Gold mining and fruit growing, in particular, were monopolized by these wealthy landowners. These "Great Owners" completely controlled local activity and, furthermore, were the principal employers and the main source of wages. This led to a society of peasants whose connection to larger political realities remained in thrall to farming and mining magnates. The endemic political instability and the nature of the economy resulted in the emergence of caudillos, military chiefs whose hold on power depended on their military skill and ability to dispense patronage. The political regimes were at least in theory democratic and took the form of either presidential or parliamentary governments. Both were prone to being taken over by a caudillo or an oligarchy. The political landscape was occupied by conservatives, who believed that the preservation of the old social hierarchies served as the best guarantee of national stability and prosperity, and liberals, who sought to bring about progress by freeing up the economy and individual initiative. Popular insurrections were often influential and repressed: 100,000 were killed during the suppression of a Colombian revolt between 1899 and 1902 during the Thousand Days' War. Some states did manage to have some of democracy: Uruguay, and partially Argentina, Chile, Costa Rica and Colombia. The others were clearly oligarchist or authoritarian, although these oligarchs and caudillos sometimes enjoyed support from a majority in the population. All of these regimes sought to maintain Latin America's lucrative position in the world economy as a provider of raw materials. 20th century1900–1929 By the start of the century, the United States continued its interventionist attitude, which aimed to directly defend its interests in the region. This was officially articulated in Theodore Roosevelt's Big Stick Doctrine, which modified the old Monroe Doctrine, which had simply aimed to deter European intervention in the hemisphere. At the conclusion of the Spanish–American War the new government of Cuba and the United States signed the Platt Amendment in 1902, which authorized the United States to intervene in Cuban affairs when the United States deemed necessary. In Colombia, United States sought the concession of a territory in Panama to build a much anticipated canal across the isthmus. The Colombian government opposed this, but a Panamanian insurrection provided the United States with an opportunity. The United States backed Panamanian independence and the new nation granted the concession. These were not the only interventions carried out in the region by the United States. In the first decades of the twentieth century, there were several military incursions into Central America and the Caribbean, mostly in defense of commercial interests, which became known as the "Banana Wars." The greatest political upheaval in the second decade of the century took place in Mexico. In 1908, President Porfirio Díaz, who had been in office since 1884, promised that he would step down in 1910. Francisco I. Madero, a moderate liberal whose aim was to modernize the country while preventing a socialist revolution, launched an election campaign in 1910. Díaz, however, changed his mind and ran for office once more. Madero was arrested on election day and Díaz declared the winner. These events provoked uprisings, which became the start of the Mexican Revolution. Revolutionary movements were organized and some key leaders appeared: Pancho Villa in the north, Emiliano Zapata in the south, and Madero in Mexico City. Madero's forces defeated the federal army in early 1911, assumed temporary control of the government and won a second election later on November 6, 1911. Madero undertook moderate reforms to implement greater democracy in the political system but failed to satisfy many of the regional leaders in what had become a revolutionary situation. Madero's failure to address agrarian claims led Zapata to break with Madero and resume the revolution. On February 18, 1913 Victoriano Huerta, a conservative general organized a coup d'état with the support of the United States; Madero was killed four days later. Other revolutionary leaders such as Villa, Zapata, and Venustiano Carranza continued to militarily oppose the federal government, now under Huerta's control. Allies Zapata and Villa took Mexico City in March 1914, but found themselves outside of their elements in the capital and withdrew to their respective bastions. This allowed Carranza to assume control of the central government. He then organized the repression of the rebel armies of Villa and Zapata, led in particular by General Álvaro Obregón. The Mexican Constitution of 1917, still the current constitution, was proclaimed but initially little enforced. The efforts against the other revolutionary leaders continued. Zapata was assassinated on April 10, 1919. Carranza himself was assassinated on May 15, 1920, leaving Obregón in power, who was officially elected president later that year. Finally in 1923 Villa was also assassinated. With the removal of the main rivals Obregón is able to consolidate power and relative peace returned to Mexico. Under the Constitution a liberal government is implemented but some of the aspirations of the working and rural classes remained unfulfilled. (See also, Agrarian land reform in Mexico.) The prestige of Germany and German culture in Latin America remained high after the war but did not recover to its pre-war levels.[21][22] Indeed, in Chile the war bought an end to a period of scientific and cultural influence writer Eduardo de la Barra scorningly called "the German bewichment" (Spanish: el embrujamiento alemán).[23] SportsSports became increasingly popular, drawing enthusiastic fans to large stadia.[24] The International Olympic Committee (IOC) worked to encourage Olympic ideals and participation. Following the 1922 Latin American Games in Rio de Janeiro, the IOC helped to establish national Olympic committees and prepare for future competition. In Brazil, however, sporting and political rivalries slowed progress as opposing factions fought to control of international sport. The 1924 Summer Olympics in Paris and the 1928 Summer Olympics in Amsterdam saw greatly increased participation from Latin American athletes.[25] English and Scottish engineers brought futebol (soccer) to Brazil in the late 1800s. The International Committee of the YMCA of North America and the Playground Association of America played major roles in training coaches. .[26] 1930–1945The Great Depression posed a great challenge to the region. The collapse of the world economy meant that the demand for raw materials drastically declined, undermining many of the economies of Latin America. Intellectuals and government leaders in Latin America turned their backs on the older economic policies and turned toward import substitution industrialization. The goal was to create self-sufficient economies, which would have their own industrial sectors and large middle classes and which would be immune to the ups and downs of the global economy. Despite the potential threats to United States commercial interests, the Roosevelt administration (1933–1945) understood that the United States could not wholly oppose import substitution. Roosevelt implemented a Good Neighbor policy and allowed the nationalization of some American companies in Latin America. Mexican President Lázaro Cárdenas nationalized American oil companies, out of which he created Pemex. Cárdenas also oversaw the redistribution of a quantity of land, fulfilling the hopes of many since the start of the Mexican Revolution. The Platt Amendment was also repealed, freeing Cuba from legal and official interference of the United States in its politics. The Second World War also brought the United States and most Latin American nations together.[27] Cold War era (1945–1992) Many Latin American economies continued to grow in the post-World War II era, but not as quickly as they had hoped. When the transatlantic trade re-opened following the peace, Europe looked as if it would need Latin American food exports and raw materials. The policies of import substitution industrialization adopted in Latin America when exports slowed due to the Great Depression and subsequent isolation in World War II were now subject to international competition. Those who supported a return to the export of commodities for which Latin America had a competitive advantage disagreed with advocates of an expanded industrial sector. The rebuilding of Europe, including Germany, with the aid of the U.S. after World War II did not bring stronger demand for Latin American exports. In Latin America, much of the hard currency earned by their participation in the war went to nationalize foreign-owned industries and pay down their debt. A number of governments set tariff and exchange rate policies that undermined the export sector and aided the urban working classes. Growth slowed in the post-war period and by the mid-1950s, the optimism of the postwar period was replaced by pessimism.[28] Following World War II, the United States policy toward Latin America focused on what it perceived as the threat of communism and the Soviet Union to the interests of Western Europe and the United States. Although Latin American countries had been staunch allies in the war and reaped some benefits from it, in the post-war period the region did not prosper as it had expected. Latin America struggled in the post-war period without large-scale aid from the U.S., which devoted its resources to rebuilding Western Europe, including Germany. In Latin America there was increasing inequality, with political consequences in the individual countries. The U.S. returned to a policy of interventionism when it felt its political and economic interests were threatened. With the breakup of the Soviet bloc in the late 1980s and early 1990s, including the Soviet Union itself, Latin America sought to find new solutions to long-standing problems. With its Soviet alliance dissolved, Cuba entered a Special Period of severe economic disruption, high death rates, and food shortages.  Deeply alarming for the U.S. were two revolutions that threaten, fed its dominance in the region. The Guatemalan Revolution (1944–54) saw the replacement of a U.S.-backed regime of Jorge Ubico in 1945 followed by elections. Reformist Juan José Arévalo (1945–51) was elected and began instituting populist reforms. Reforms included land laws that threatened the interests of large foreign-owned enterprises, a social security law, workmen's compensation, laws allowing labor to organize and strike, and universal suffrage except for illiterate women. His government established diplomatic ties with the Soviet Union in April 1945, when the Soviet Union and the U.S. were allied against the Axis powers. Communists entered leadership positions in the labor movement. At the end of his term, his hand-picked successor, the populist and nationalist Jacobo Arbenz, was elected. Arbenz proposed placing capital in the hands of Guatemalans, building new infrastructure, and significant land reform via Decree 900. With what the U.S. considered the prospect of even more radical changes in Guatemala, it backed a coup against Arbenz in 1954, overthrowing him.[29][30][31] Argentine Che Guevara was in Guatemala during the Arbenz presidency; the coup ousting Arbenz was instructive for him and for Latin American nations seeking significant structural change.[32] In 1954 the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency aided successful military coup against Arbenz.  The 1959 Cuban Revolution led by Cuban lawyer Fidel Castro overthrew the regime of Fulgencio Batista, with 1 January 1959 marking as the revolution's victory. The revolution was a huge event not only in Cuban history, but also the history of Latin America and the world. Almost the immediately, the U.S. reacted with hostility against the new regime. As the revolutionaries began consolidating power, many middle- and upper-class Cubans left for the U.S., likely not expecting the Castro regime to last long. Cuba became a poorer and blacker country, and the Cuba Revolution sought to transform the social and economic inequalities and political instability of the previous regimes into a more socially and economically equal one. The government put emphasis on literacy as a key to Cuba's overall betterment, essentially wiping out illiteracy after an early major literacy campaign. Schools became a means to instill in Cuban students messages of nationalism, solidarity with the Third World, and Marxism.[citation needed] Cuba also made a commitment to universal health care, so the education of doctors and construction of hospitals were top priorities. Cuba also sought to diversify its economy, until then based mainly on sugar, but also tobacco.[33] The U.S. attempted to overthrow Castro, using the template of the successful 1954 coup in Guatemala. In the April 1961 Bay of Pigs invasion, Cuba entered into a formal alliance with the Soviet Union. In February 1962, the U.S. placed an embargo on trade with Cuba, which remains in force as of 2021.[34] In February 1962, the U.S. pressured members of the Organization of American States to expel Cuba, attempting to isolate it. In response to the Bay of Pigs, Cuba called for revolution in the Americas. The efforts ultimately failed, most notably with Che Guevara in Bolivia, where he was isolated, captured, and executed. When the U.S. discovered that the Soviet Union had placed missiles in Cuba in 1962, they reacted swiftly with a showdown now called the Cuban Missile Crisis, which ended with an agreement between the U.S. and the Soviet Union, who did not consult Cuba about its terms. One term of the agreement was that the U.S. would cease efforts to invade Cuba, a guarantee of its sovereignty. However, the U.S. continued to attempt to remove Castro from power by assassination. The Soviet Union continued to materially support the Cuban regime, providing oil and other petrochemicals, technical support, and other aid, in exchange for Cuban sugar and tobacco.[35]  From 1959 to 1992, Fidel Castro ruled as a caudillo, or strong man, dominating politics and the international stage. His commitment to social and economic equality brought about positive changes in Cuba, including the improvement of the position of women, eliminating prostitution, reducing homelessness, and raising the standard of living for most Cubans. However, Cuba lacks freedom of expression; dissenters were monitored by the Committees for the Defense of the Revolution, and travel was restricted.[36] In 1980, Castro told Cubans who wanted to leave to do so, promising that the government would not stop them. The Mariel boatlift saw some 125,000 Cubans sail from the Cuban port of Mariel, across the straits to the U.S., where U.S. President Carter initially welcomed them.[37] The Cuban Revolution had a tremendous impact not just on Cuba, but on Latin America as a whole, and the world. The Cuban Revolution was for many countries an inspiration and a model, but for the U.S. it was a challenge to its power and influence in Latin America. After leftists took power in Chile (1970) and Nicaragua (1979), Fidel Castro visited them both, extending Cuban solidarity. In Chile, Salvador Allende and a coalition of leftists, Unidad Popular, won an electoral victory in 1970 and lasted until the violent military coup of 11 September 1973. In the Nicaragua leftists held power from 1979 to 1990. The U.S. was concerned with the spread of communism in Latin America, and U.S. President Dwight Eisenhower responded to the threat he saw in the Dominican Republic's dictator Rafael Trujillo, who voiced a desire to seek an alliance with the Soviet Union. In 1961, Trujillo was murdered with weapons supplied by the CIA.[38] U.S. President John F. Kennedy initiated the Alliance for Progress in 1961, to establish economic cooperation between the U.S. and Latin America and provide $20 billion for reform and counterinsurgency measures. The reform failed because of the simplistic theory that guided it and the lack of experienced American experts who understood Latin American customs.[citation needed] From 1966 to the late 1980s, the Soviet government upgraded Cuba's military capabilities, and Cuba was active in foreign interventions, assisting with movements in several countries in Latin America and elsewhere in the world. Most notable were the MPLA during the Angolan Civil War and the Derg during the Ogaden War. They also supported governments and rebel movements in Syria, Mozambique, Algeria, Venezuela, Bolivia, and Vietnam.[39][40]  In Chile, the postwar period saw uneven economic development. The mining sector (copper, nitrates) continued to be important, but an industrial sector also emerged. The agricultural sector stagnated and Chile needed to import foodstuffs. After the 1958 election, Chile entered a period of reform. The secret ballot was introduced, the Communist Party was relegalized, and populism grew in the countryside. In 1970, democratic elections brought to power socialist Salvador Allende, who implemented many reforms begun in 1964 under Christian Democrat Eduardo Frei. The economy continued to depend on mineral exports and a large portion of the population reaped no benefits from the prosperity and modernity of some sectors. Chile had a long tradition of stable electoral democracy, In the 1970 election, a coalition of leftists, the Unidad Popular ("popular unity") candidate Allende was elected. Allende and his coalition held power for three years, with the increasing hostility of the U.S. The Chilean military staged a bloody coup with US support in 1973. The military under General Augusto Pinochet then held power until 1990.   The 1970s and 1980s saw a large and complex political conflict in Central America. The U.S. administration of Ronald Reagan funded right-wing governments and proxy fighters against left-wing challenges to the political order. Complicating matters were the liberation theology emerging in the Catholic Church and the rapid growth of evangelical Christianity, which were entwined with politics. The Nicaraguan Revolution revealed the country as a major proxy war battleground in the Cold War. Although the initial overthrow of the Somoza regime in 1978–79 was a bloody affair, the Contra War of the 1980s took the lives of tens of thousands of Nicaraguans and was the subject of fierce international debate.[41] During the 1980s both the FSLN (a leftist collection of political parties) and the Contras (a rightist collection of counter-revolutionary groups) received considerable aid from the Cold War superpowers. The Sandinistas allowed free elections in 1990 and after years of war, lost the election. They became the opposition party, following a peaceful transfer of power. A civil war in El Salvador pitted leftist guerrillas against a repressive government. The bloody war there ended in a stalemate, and following the fall of the Soviet Union, a negotiated peace accord ended the conflict in 1992. In Guatemala, the civil war included genocide of Mayan peasants. A peace accord was reached in 1996 and the Catholic Church called for a truth and reconciliation commission.  In the religious sphere, the Roman Catholic Church continued to be a major institution in nineteenth-century Latin America. For a number of countries in the nineteenth century, especially Mexico, liberals viewed the Catholic Church as an intransigent obstacle to modernization, and when liberals gained power, anticlericalism was written into law, such as the Mexican liberal Constitution of 1857 and the Uruguayan Constitution of 1913 which secularized the state. Nevertheless, most Latin Americans identified as Catholic, even if they did not attend church regularly. Many followed folk Catholicism, venerated saints, and celebrated religious festivals. Many communities did not have a resident priest or even visits by priests to keep contact between the institutional church and the people. In the 1950s, evangelical Protestants began proselytizing in Latin America. In Brazil, the Catholic bishops organized themselves into a national council, aimed at better meeting the competition not only of Protestants, but also of secular socialism and communism. Following Vatican II (1962–65) called by Pope John XXIII, the Catholic Church initiated a series of major reforms empowering the laity. Pope Paul VI actively implemented reforms and sought to align the Catholic Church on the side of the dispossessed, ("preferential option for the poor"), rather than remain a bulwark of conservative elites and right-wing repressive regimes. Colombian Catholic priest Camilo Torres took up arms with the Colombian guerrilla movement ELN, which modeled itself on Cuba but was killed in his first combat in 1966.[42] In 1968, Pope Paul came to the meeting of Latin American bishops in Medellín, Colombia. Peruvian priest Gustavo Gutiérrez was one of the founders of liberation theology, a term he coined in 1968, sometimes described as linking Christianity and Marxism. Conservatives saw the church as politicized, and priests ask proselytizing leftist positions. Priests became targets as "subversives", such as Salvadoran Jesuit Rutilio Grande. Archbishop of El Salvador Óscar Romero called for an end to persecution of the church, and took positions of social justice. He was assassinated on 24 March 1980 while saying mass. Liberation theology informed the struggle by Nicaraguan leftists against the Somoza dictatorship, and when they came to power in 1979, the ruling group included some priests. When a Polish cleric became Pope John Paul II following the death of Paul VI, and the brief papacy of John Paul I, he reversed the progressive position of the church, evident in the 1979 Puebla conference of Latin American bishops. On a papal visit to Nicaragua in 1983, he reprimanded Father Ernesto Cardenal, who was Minister of Culture, and called on priests to leave politics. Brazilian theologian Leonardo Boff was silenced by the Vatican. Despite the Vatican stance against liberation theology, articulated in 1984 by Cardinal Josef Ratzinger, later Pope Benedict XVI, many Catholic clergy and laity worked against repressive military regimes. After a military coup ousted the democratically elected Salvador Allende, the Chilean Catholic Church was a force in opposition to the regime of Augusto Pinochet and for human rights. The Argentine Church did not follow the Chilean pattern of opposition however.[43] When Jesuit Jorge Bergoglio was elected Pope Francis, his actions during the Dirty War were an issue, as portrayed in the film The Two Popes.  Although most countries did not have Catholicism as the established religion, Protestantism made few inroads in the region until the late twentieth century. Evangelical Protestants, particularly Pentecostals, proselytized and gained adherents in Brazil, Central America, and elsewhere. In Brazil, Pentecostals had a long history. But in a number of countries ruled by military dictatorships many Catholics followed the social and political teachings of liberation theology and were seen as subversives. Under these conditions, the influence of religious non-Catholics grew. Evangelical churches often grew quickly in poor communities where small churches and members could participate in ecstatic worship, often many times a week. Pastors in these churches did attend a seminary nor were there other institutional requirements. In some cases, the first evangelical pastors came from the U.S., but these churches quickly became "Latin Americanized," with local pastors building religious communities. In some countries, they gained a significant hold and were not persecuted by military dictators, since they were largely apolitical.[44] In Guatemala under General Efraín Ríos Montt, an evangelical Christian, Catholic Maya peasants were targeted as subversives and slaughtered. Perpetrators were later put on trial in Guatemala, including Ríos Montt. Post–Cold War era After the fall of the Soviet Union, the Cold War which saw U.S. intervention in Latin America as preventing Soviet influence dissipating. The Central American wars ended, with a free and fair election in Nicaragua that voted out the leftist Sandinistas, a peace treaty was concluded between factions in El Salvador, and the Guatemalan civil war ended. Cuba had lost its political and economic patron, the Soviet Union, which could no longer provide support. Cuba entered what is known there are the Special Period, when the economy contracted severely, but the revolutionary government nonetheless retained power and the U.S. remained hostile to its revolution. U.S. policy-makers developed the Washington Consensus, a set of specific economic policy prescriptions considered the standard reform package for crisis-wracked developing countries by Washington, D.C.–based institutions such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the World Bank, and the US Department of the Treasury during the 1980s and 1990s. The term has become associated with neoliberal policies in general and drawn into the broader debate over the expanding role of the free market, constraints upon the state, and US influence on other countries' national sovereignty. The politico-economical initiative was institutionalized in North America by the 1994 NAFTA, and elsewhere in the Americas through a series of similar agreements. The comprehensive Free Trade Area of the Americas project, however, was rejected by most South American countries at the 4th Summit of the Americas in 2005. A debt crisis ensured after 1982 when the price of oil crashed and Mexico announced that it could not meet its foreign debt payment obligations. Other Latin American economies followed suit, with hyperinflation and the inability of governments to meet their debt obligations and the era became known as the "lost decade."[45] The debt crisis would lead to neoliberal reforms that would instigate many social movements in the region. A "reversal of development" reigned over Latin America, seen through negative economic growth, declines in industrial production, and thus, falling living standards for the middle and lower classes.[46] Governments made financial security their primary policy goal over social programs, enacting new neoliberal economic policies that implemented privatization of previously national industries and the informal sector of labor.[45] In an effort to bring more investors to these industries, these governments also embraced globalization through more open interactions with the international economy. Significantly, democratic governments began replacing military regimes across much of Latin America and the realm of the state became more inclusive (a trend that proved conducive to social movements), but economic ventures remained exclusive to a few elite groups within society. Neoliberal restructuring consistently redistributed income upward, while denying political responsibility to provide social welfare rights, and development projects throughout the region increased both inequality and poverty.[45] Feeling excluded from the new projects, the lower classes took ownership of their own democracy through a revitalization of social movements in Latin America.  Both urban and rural populations had serious grievances as a result of economic and global trends and voiced them in mass demonstrations. Some of the largest and most violent have been protests against cuts in urban services to the poor, such as the Caracazo in Venezuela and the Argentinazo in Argentina.[47] In 2000, the Cochabamba Water War in Bolivia saw major protests against a World Bank-funded project that would have brought potable water to the city, but at a price that no residents could afford.[48] The title of the Oscar nominated film Even the Rain alludes to the fact that Cochabamba residents could no longer legally collect rainwater; the film depicts the protest movement. Rural movements made demands related to unequal land distribution, displacement at the hands of development projects and dams, environmental and Indigenous concerns, neoliberal agricultural restructuring, and insufficient means of livelihood. In Bolivia, coca workers organized into a union, and Evo Morales, ethnically an Aymara, became its head. The cocaleros supported the struggles in the Cochabamba water war. The rural-urban coalition became a political party, Movement for Socialism (Bolivia) (MAS, "more"), which decisively won the 2005 presidential election, making Evo Morales the first Indigenous president of Bolivia. A documentary of the campaign, Cocalero, shows how they successfully organized.[49] A number of movements have benefited considerably from transnational support from conservationists and INGOs. The Movement of Rural Landless Workers (MST) in Brazil for example is an important contemporary Latin American social movement.[47] Indigenous movements account for a large portion of rural social movements, including, in Mexico, the Zapatista rebellion and the broad Indigenous movement in Guerrero,[50] Also important are the Confederation of Indigenous Nationalities of Ecuador (CONAIE) and Indigenous organizations in the Amazon region of Ecuador and Bolivia, pan-Mayan communities in Guatemala, and mobilization by the Indigenous groups of Yanomami peoples in the Amazon, Kuna peoples in Panama, and Altiplano Aymara and Quechua peoples in Bolivia.[47] 21st centuryTurn to the left Since the 2000s, or 1990s in some countries, left-wing political parties have risen to power. Hugo Chávez in Venezuela, Lula da Silva and Dilma Rousseff in Brazil, Fernando Lugo in Paraguay, Néstor and Cristina Kirchner in Argentina, Tabaré Vázquez and José Mujica in Uruguay, the Lagos and Bachelet governments in Chile, Evo Morales in Bolivia, Daniel Ortega in Nicaragua, Manuel Zelaya in Honduras (although deposed by the 28 June 2009 coup d'état), and Rafael Correa of Ecuador are all part of this wave of left-wing politicians, who also often declare themselves socialists, Latin Americanists or anti-imperialists. Turn to the right and resurgence of the left The conservative wave (Portuguese: onda conservadora) is a political phenomenon that emerged in mid-2010 in South America. In Brazil, it began roughly around the time Dilma Rousseff, in a tight election, won the 2014 presidential election, kicking off the fourth term of the Workers' Party in the highest position of government.[51] In addition, according to the political analyst of the Inter-Union Department of Parliamentary Advice, Antônio Augusto de Queiroz, the National Congress elected in 2014 may be considered the most conservative since the "re-democratization" movement, noting an increase in the number of parliamentarians linked to more conservative segments, as ruralists, military, police and religious. The subsequent economic crisis of 2015 and investigations of corruption scandals led to a right-wing movement that sought to rescue ideas from economic liberalism and conservatism in opposition to left-wing policies.[52] A resurgence of the rise of left-wing political parties in Latin America by their electoral victories, however, was initiated by Mexico in 2018 and Argentina in 2019, and further strengthened by Bolivia in 2020 along with Peru, Honduras and Chile in 2021 and Colombia and Brazil in 2022.[53] However, right-wing candidates won both Ecuador’s and Argentina's presidential elections in 2023.[54][55] See also

Pre-Columbian

ColonizationBritish colonization of the Americas, Danish colonization of the Americas, Dutch colonization of the Americas, New Netherland, French New France, Portuguese, Russian, Spanish, New Spain, Conquistador, Spanish conquest of Yucatán, Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire, Spanish missions in California, Swedish History by regionHistory by countryOther topics

References

Further reading

Historiography

Colonial era

Independence era

Modern era

|