|

Paraguayan War

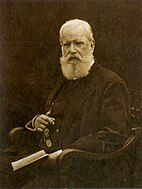

The Paraguayan War (Spanish: Guerra del Paraguay, Portuguese: Guerra do Paraguai, Guarani: Paraguái Ñorairõ), also known as the War of the Triple Alliance (Spanish: Guerra de la Triple Alianza, Portuguese: Guerra da Tríplice Aliança), was a South American war that lasted from 1864 to 1870. It was fought between Paraguay and the Triple Alliance of Argentina, the Empire of Brazil, and Uruguay. It was the deadliest and bloodiest inter-state war in Latin American history.[6] Paraguay sustained large casualties, but even the approximate numbers are disputed. Paraguay was forced to cede disputed territory to Argentina and Brazil. The war began in late 1864, as a result of a conflict between Paraguay and Brazil caused by the Uruguayan War. Argentina and Uruguay entered the war against Paraguay in 1865, and it then became known as the "War of the Triple Alliance." After Paraguay was defeated in conventional warfare, it conducted a drawn-out guerrilla resistance, a strategy that resulted in the further destruction of the Paraguayan military and the civilian population. Much of the civilian population died due to battle, hunger, and disease. The guerrilla war lasted for 14 months until president Francisco Solano López was killed in action by Brazilian forces in the Battle of Cerro Corá on 1 March 1870. Argentine and Brazilian troops occupied Paraguay until 1876. BackgroundTerritorial disputes Since their independence from Portugal and Spain in the early 19th century, the Empire of Brazil and the Spanish-American countries of South America were troubled by territorial disputes. Each nation in this region had boundary conflicts with multiple neighbors. Most had overlapping claims to the same territories, due to unresolved questions which stemmed from their former metropoles. Signed by Portugal and Spain in 1494, the Treaty of Tordesillas proved ineffective in the following centuries, as both colonial powers expanded their frontiers in South America and elsewhere. The outdated boundary lines did not represent the actual occupation of lands by the Portuguese and Spanish. By the early 1700s, the Treaty of Tordesillas was deemed not useful, and it was clear to both parties that a newer treaty had to be drawn based on feasible boundaries. In 1750, the Treaty of Madrid separated the Portuguese and Spanish areas of South America in lines that mostly corresponded to present-day boundaries. Neither Portugal nor Spain was satisfied with the results, and new treaties were signed in the following decades that either established new territorial lines or repealed them. The final accord signed by both powers, the 1801 Treaty of Badajoz, reaffirmed the validity of the previous Treaty of San Ildefonso (1777), which had derived from the older Treaty of Madrid. The territorial disputes became worse when the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata collapsed in the early 1810s, leading to the rise of Argentina, Paraguay, Bolivia, and Uruguay. Historian Pelham Horton Box wrote: "Imperial Spain bequeathed to the emancipated Spanish-American nations not only her own frontier disputes with Portuguese Brazil but problems which had not disturbed her, relating to the exact boundaries of her own viceroyalties, captaincies general, audiencias and provinces."[7] Once separated the three countries quarreled over lands that were mostly uncharted or unknown. They were either sparsely populated or settled by indigenous tribes that answered to no parties.[8][9] In the case of Paraguay and Brazil, the problem was to define whether the Apa or Branco rivers should represent their actual boundary, a persistent issue that had confused Spain and Portugal in the late 18th century. A few indigenous tribes populated the region between the two rivers, and these tribes would attack Brazilian and Paraguayan settlements that were local to them.[10][11] Political situation before the warThere are several theories regarding the origins of the war. The traditional view emphasizes that the policies of Paraguayan president Francisco Solano López used the Uruguayan War as a pretext to gain control of the Platine basin. That caused a response from the regional hegemons, Brazil and Argentina, both of which exercised influence over the much smaller republics of Uruguay and Paraguay. The war has also been attributed to the aftermath of colonialism in South America with border conflicts between the new states, the struggle for power among neighboring nations over the strategic Río de la Plata region, Brazilian and Argentine meddling in internal Uruguayan politics (which had already caused the Platine War), Solano López's efforts to help his allies in Uruguay (which had been defeated by the Brazilians), and his presumed expansionist ambitions.[12] A strong military was developed because Paraguay's larger neighbors, Argentina and Brazil, had territorial claims against it and wanted to dominate it politically, much as both had already done in Uruguay. Paraguay had recurring boundary disputes and tariff issues with Argentina and Brazil for many years during the rule of Solano Lopez's predecessor and father, Carlos Antonio López. Regional tensionIn the time since Brazil and Argentina had become independent, their struggle for hegemony in the Río de la Plata region had profoundly marked the diplomatic and political relations among the countries of the region.[13] Brazil was the first country to recognize the independence of Paraguay, in 1844. At this time Argentina still considered it a breakaway province. While Argentina was ruled by Juan Manuel Rosas (1829–1852), a common enemy of both Brazil and Paraguay, Brazil contributed to the improvement of the fortifications and development of the Paraguayan army, sending officials and technical help to Asunción. As no roads linked the inland province of Mato Grosso to Rio de Janeiro, Brazilian ships needed to travel through Paraguayan territory, going up the Paraguay River to arrive at Cuiabá. However, Brazil had difficulty obtaining permission from the government in Asunción to freely use the Paraguay River for its shipping needs. Uruguayan preludePedro II, Emperor of Brazil from 1831 to 1889 Bartolomé Mitre, President of Argentina from 1862 to 1868 Venancio Flores, President of Uruguay from 1865 to 1868 Francisco Solano López, President of Paraguay from 1862 to 1870 Brazil had carried out three political and military interventions in the politically unstable Uruguay:

On 19 April 1863, Uruguayan general Venancio Flores, who was then an officer in the Argentine army as well as the leader of the Colorado Party of Uruguay,[14] invaded his country, starting the Cruzada Libertadora with the open support of Argentina, which supplied the rebels with arms, ammunition and 2,000 men.[15] Flores wanted to overthrow the Blanco Party government of president Bernardo Berro,[16]: 24 which was allied with Paraguay.[16]: 24 Paraguayan president López sent a note to the Argentine government on 6 September 1863, asking for an explanation, but Buenos Aires denied any involvement in Uruguay.[16]: 24 From that moment, mandatory military service was introduced in Paraguay; in February 1864, an additional 64,000 men were drafted into the army.[16]: 24 One year after the beginning of the Cruzada Libertadora, in April 1864, Brazilian minister José Antônio Saraiva arrived in Uruguayan waters with the Imperial Fleet, to demand payment for damages caused to Rio Grande do Sul farmers in border conflicts with Uruguayan farmers. Uruguayan president Atanasio Aguirre, from the Blanco Party, rejected the Brazilian demands, presented his own demands, and asked Paraguay for help.[17] To settle the growing crisis, Solano López offered himself as a mediator of the Uruguayan crisis, as he was a political and diplomatic ally of the Uruguayan Blancos, but the offer was turned down by Brazil.[18] Brazilian soldiers on the northern borders of Uruguay started to provide help to Flores' troops and harassed Uruguayan officers, while the Imperial Fleet pressed hard on Montevideo.[19] During the months of June–August 1864 a Cooperation Treaty was signed between Brazil and Argentina at Buenos Aires, for mutual assistance in the Plate Basin Crisis.[20] Brazilian minister Saraiva sent an ultimatum to the Uruguayan government on 4 August 1864: either comply with the Brazilian demands, or the Brazilian army would retaliate.[21] The Paraguayan government was informed of all this and sent to Brazil a message, which stated in part:

The Brazilian government, probably believing that the Paraguayan threat would be only diplomatic, answered on 1 September, stating that "they will never abandon the duty of protecting the lives and interests of Brazilian subjects." But in its answer, two days later, the Paraguayan government insisted that "if Brazil takes the measures protested against in the note of August 30th, 1864, Paraguay will be under the painful necessity of making its protest effective."[23] On 12 October, despite the Paraguayan notes and ultimatums, Brazilian troops under the command of general João Propício Mena Barreto invaded Uruguay.[16]: 24 This was not the start of the Paraguayan war, however, for Paraguay continued to maintain diplomatic relations with Brazil for another month. On 11 November the Brazilian ship Marquês de Olinda, on her routine voyage up the River Paraguay to the Brazilian Mato Grosso, and carrying the new governor of that province, docked at Asunción and took on coal. Completing the formalities, she continued on her journey. According to one source, López hesitated whether to break the peace for a whole day, saying "If we don't have a war now with Brazil, we shall have one at a less convenient time for ourselves".[24] López then ordered the Paraguayan ship Tacuarí to pursue her and compel her return. On 12 November Tacuarí caught up with Marquês de Olinda in the vicinity of Concepción, fired across her bows, and ordered her to return to Asunción; when she arrived on the 13th, all on board were arrested. On the 12th Paraguay informed the Brazilian minister in Asunción that diplomatic relations had been broken off.[25] The conflict between Brazil and Uruguay was settled in February 1865. News of the war's end was brought by Pereira Pinto and met with joy in Rio de Janeiro. Brazilian emperor Pedro II found himself waylaid by a crowd of thousands in the streets amid acclamations.[26][27] However, public opinion quickly changed for the worse when newspapers began running stories painting the convention of 20 February as harmful to Brazilian interests, for which the cabinet was blamed. The newly promoted Viscount of Tamandaré and Mena Barreto (now Baron of São Gabriel) had supported the peace accord.[28] Tamandaré changed his mind soon afterward and played along with the allegations. A member of the opposition party, José Paranhos, Viscount of Rio Branco, was used as a scapegoat by the emperor and the government and was recalled in disgrace to the imperial capital.[29] The accusation that the convention had failed to meet Brazilian interests proved to be unfounded. Not only had Paranhos managed to settle all Brazilian claims, but by preventing the death of thousands, he gained a willing and grateful Uruguayan ally instead of a dubious and resentful one, which provided Brazil with an important base of operations during the acute clash with Paraguay that shortly ensued.[30] Opposing forces ParaguayAccording to some historians,[who?] Paraguay began the war with over 60,000 trained men—38,000 of whom were already under arms—400 cannons, a naval squadron of 23 steamboats and five river-navigating ships (among them, the gunboat Tacuarí).[31] Communication in the Río de la Plata basin was maintained solely by river, as very few roads existed. Whoever controlled the rivers would win the war, so Paraguay had built fortifications on the banks of the lower end of the Paraguay River.[16]: 28–30 However, recent studies[which?] suggest many problems. Although the Paraguayan army had between 70,000 and 100,000 men at the beginning of the conflict, they were badly equipped. Most infantry armaments consisted of inaccurate smooth-bore muskets and carbines, slow to reload and short-ranged. The artillery was similarly poor. Military officers had no training or experience, and there was no command system, as all decisions were made personally by López. Food, ammunition, and armaments were scarce, with logistics and hospital care deficient or nonexistent.[32] The nation of about 450,000 people could not stand against the Triple Alliance of 11 million people. The Paraguayan army during peacetime prior to the war was made up of eight infantry battalions of 800 men each but had only been able to muster 4,084 Infantrymen with five cavalry regiments, nominally 2,500 (2,522 in reality) and two artillery regiments, with 907 men. By March 1865, six new infantry battalions and eight cavalry regiments had been formed. In addition, the Paraguayans could rely on their militia which consisted of all able-bodied men which, as the war continued, began to include increasingly younger and older men.[33] Brazil and its allies At the beginning of the war, the military forces of Brazil, Argentina, and Uruguay were far smaller than Paraguay's. Argentina had approximately 8,500 regular troops and a naval squadron of four steamers and one schooner. Uruguay entered the war with fewer than 2,000 men and no navy. Many of Brazil's 16,000 troops were located in its southern garrisons.[34] The Brazilian advantage, though, was in its navy, comprising 45 ships with 239 cannons and about 4,000 well-trained crew. A great part of the squadron was already in the Rio de la Plata basin, where it had acted under the Marquis of Tamandaré in the intervention against Aguirre's government. Brazil, however, was unprepared to fight a war. Its army was disorganized. The troops it used in Uruguay were mostly armed contingents of gauchos and the National Guard. While some Brazilian accounts of the war described their infantry as volunteers (Voluntários da Pátria), other Argentine revisionist and Paraguayan accounts disparaged the Brazilian infantry as mainly recruited from slaves and the landless (largely black) underclass, who were promised free land for enlisting.[35] The cavalry was formed from the National Guard of Rio Grande do Sul. Ultimately, a total of about 146,000 Brazilians fought in the war from 1864 to 1870, consisting of the 10,025 army soldiers stationed in Uruguayan territory in 1864, 2,047 that were in the province of Mato Grosso, 55,985 Fatherland Volunteers, 60,009 National Guardsmen, 8,570 ex-slaves who had been freed to be sent to war, and 9,177 navy personnel. Another 18,000 National Guard troops stayed behind to defend Brazilian territory.[36] Course of the warParaguayan offensiveIn Mato Grosso Paraguay took the initiative during the first phase of the war, launching the Mato Grosso Campaign by invading the Brazilian province of Mato Grosso on 14 December 1864,[16]: 25 followed by an invasion of the Rio Grande do Sul province in the south in early 1865 and the Argentine Corrientes Province. Two separate Paraguayan forces invaded Mato Grosso simultaneously. An expedition of 3,248 troops, commanded by Vicente Barrios, was transported by a naval squadron under the command of frigate captain Pedro Ignacio Meza up the Paraguay River to the town of Concepción.[16]: 25 There they attacked the New Coimbra Fort on 27 December 1864.[16]: 26 The Brazilian garrison of 154 men resisted for three days, under the command of Hermenegildo Portocarrero (later Baron of Fort Coimbra). When their munitions were exhausted, the defenders abandoned the fort and withdrew up the river towards Corumbá on board the gunship Anhambaí.[16]: 26 After occupying the fort, the Paraguayans advanced further north, taking the cities of Albuquerque, Tage and Corumbá in January 1865.[16]: 26 Solano López then sent a detachment to attack the military frontier post of Dourados. On 29 December 1864, this detachment, led by Martín Urbieta, encountered tough resistance from Antônio João Ribeiro and his 16 men, who were all eventually killed. The Paraguayans continued to Nioaque and Miranda, defeating the troops of José Dias da Silva. The city of Coxim was taken in April 1865. The second Paraguayan column, formed from some of the 4,650 men led by Francisco Isidoro Resquín at Concepción, penetrated into Mato Grosso with 1,500 troops.[16]: 26 Despite these victories, the Paraguayan forces did not continue to Cuiabá, the capital of the province, where Augusto Leverger had fortified the camp of Melgaço. Their main objective was the capture of the gold and diamond mines, disrupting the flow of these materials into Brazil until 1869.[16]: 27 Brazil sent an expedition to fight the invaders in Mato Grosso. A column of 2,780 men led by Manuel Pedro Drago left Uberaba in Minas Gerais in April 1865 and arrived at Coxim in December, after a difficult march of more than 2,000 kilometres (1,200 mi) through four provinces. However, Paraguay had already abandoned Coxim by December. Drago arrived at Miranda in September 1866, and the Paraguayans had left once again. Colonel Carlos de Morais Camisão assumed command of the column in January 1867—now with only 1,680 men—and decided to invade Paraguayan territory, which he penetrated as far as Laguna[37] where Paraguayan cavalry forced the expedition to retreat. Despite the efforts of Camisão's troops and the resistance in the region, which succeeded in liberating Corumbá in June 1867, a large portion of Mato Grosso remained under Paraguayan control. The Brazilians withdrew from the area in April 1868, moving their troops to the main theatre of operations, in the south of Paraguay. Paraguayan invasion of Corrientes and Rio Grande do Sul The invasion of Corrientes and Rio Grande do Sul was the second phase of the Paraguayan offensive. In order to support the Uruguayan Blancos, the Paraguayans had to travel across Argentine territory. In January 1865, Solano López asked Argentina's permission for an army of 20,000 men (led by general Wenceslao Robles) to travel through the province of Corrientes.[16]: 29–30 Argentine president Bartolomé Mitre refused Paraguay's request and a similar one from Brazil.[16]: 29 After this refusal, the Paraguayan Congress gathered at an emergency meeting on 5 March 1865. After several days of discussions, on 23 March Congress decided to declare war on Argentina for its policies, hostile to Paraguay and favourable to Brazil, and then they conferred to Francisco Solano López the rank of Field Marshal of the Republic of Paraguay. The declaration of war was sent on 29 March 1865 to Buenos Aires.[38] On 13 April 1865, a Paraguayan squadron sailed down the Paraná River and attacked two Argentine ships in the port of Corrientes. Immediately general Robles' troops took the city with 3,000 men, and a cavalry force of 800 arrived the same day. Leaving a force of 1,500 men in the city, Robles advanced southwards along the eastern bank.[16]: 30 Along with Robles' troops, a force of 12,000 soldiers under colonel Antonio de la Cruz Estigarribia crossed the Argentine border south of Encarnación in May 1865, driving for Rio Grande do Sul. They traveled down the Uruguay River and took the town of São Borja on 12 June. Uruguaiana, to the south, was taken on 6 August with little resistance. By invading Corrientes, Solano López had hoped to gain the support of the powerful Argentine caudillo Justo José de Urquiza, governor of the provinces of Corrientes and Entre Ríos, who was known to be the chief federalist hostile to Mitre and the central government in Buenos Aires.[39] However, Urquiza gave his full support to an Argentine offensive.[16]: 31 The forces advanced approximately 200 kilometres (120 mi) south before ultimately ending the offensive in failure. Following the invasion of the Corrientes Province by Paraguay on 13 April 1865, a great uproar stirred in Buenos Aires as the public learned of Paraguay's declaration of war. President Bartolomé Mitre made a famous speech to the crowds on 4 May 1865:

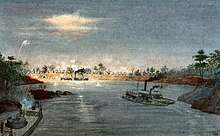

The same day, Argentina declared war on Paraguay;[16]: 30–31 however, on 1 May 1865, Brazil, Argentina, and Uruguay had signed the secret Treaty of the Triple Alliance in Buenos Aires. They named Bartolomé Mitre, president of Argentina, as supreme commander of the allied forces.[39] The signatories of the treaty were Rufino de Elizalde (Argentina), Otaviano de Almeida (Brazil) and Carlos de Castro (Uruguay).  On 11 June 1865, at the naval Battle of Riachuelo, the Brazilian fleet commanded by admiral Francisco Manoel Barroso da Silva destroyed the Paraguayan navy and prevented the Paraguayans from permanently occupying Argentine territory. For all practical purposes, this battle decided the outcome of the war in favor of the Triple Alliance; from that point onward, it controlled the waters of the Río de la Plata basin up to the entrance to Paraguay.[41] A separate Paraguayan division of 3,200 men that continued towards Uruguay under the command of Pedro Duarte, who was then defeated by Allied troops under Venancio Flores in the bloody Battle of Yatay, on the banks of the Uruguay River, near Paso de los Libres. While Solano López ordered the retreat of the forces that had occupied Corrientes, the Paraguayan troops that invaded São Borja advanced, taking Itaqui and Uruguaiana. The situation in Rio Grande do Sul was chaotic, and the local Brazilian military commanders were incapable of mounting effective resistance to the Paraguayans.[42] The baron of Porto Alegre set out for Uruguaiana, a small town in the province's west, where the Paraguayan army was besieged by a combined force of Brazilian, Argentine and Uruguayan units.[43] Porto Alegre assumed command of the Brazilian army in Uruguaiana on 21 August 1865.[44] On 18 September, the Paraguayan garrison surrendered without further bloodshed.[45] Allied counterattackIn subsequent months, the Paraguayans were driven out of the cities of Corrientes and San Cosme, the only Argentine territory still in Paraguayan possession. By the end of 1865, the Triple Alliance was on the offensive. Its armies numbered 42,000 infantry and 15,000 cavalry as they invaded Paraguay in April.[16]: 51–52 The Paraguayans scored small victories against major forces in the Battle of Corrales (also known as battle of Pehuajó or Itati) in the Corrientes Province, but it could not stop the invasion.[46] Invasion of Paraguay On 16 April 1866, the Allied armies invaded Paraguayan mainland by crossing the Paraná River.[47] López launched counterattacks, but they were repelled by general Manuel Luís Osório, who took victories in the battles of Itapirú and Isla Cabrita. Yet, the Allied advance was checked in the first major battle of the war, at Estero Bellaco, on 2 May 1866.[48] Solano López, believing that he could deal a fatal blow to the Allies, launched a major offensive with 25,000 men against 35,000 Allied soldiers at the Battle of Tuyutí on 24 May 1866, one of the bloodiest battles in Latin-American history.[49] Despite being very close to victory at Tuyutí, López's plan was shattered by the Allied army's fierce resistance and the decisive action of the Brazilian artillery.[50] Both sides sustained heavy losses: more than 12,000 casualties for Paraguay versus 6,000 for the Allies.[51][52] By 18 July, the Paraguayans had recovered, defeating forces commanded by Mitre and Flores in the Battle of Sauce and Boquerón, losing more than 2,000 men against the Allied 6,000 casualties.[53] However, Brazilian general Porto Alegre[54] won the Battle of Curuzú, putting the Paraguayans in a desperate situation.[55] On 12 September 1866, after the defeat in the Battle of Curuzú, Solano López invited Mitre and Flores to a conference in Yataytí Corá, which resulted in a "heated argument" among both leaders.[16]: 62 López had realized that the war was lost and was ready to sign a peace treaty with the Allies.[56] However, no agreement was reached, since Mitre's conditions for signing the treaty were that every article of the Treaty of the Triple Alliance was to be carried out, a condition that Solano López refused.[56] Article 6 of the treaty made truce or peace with López nearly impossible, as it stipulated that the war was to continue until the then government ceased to be, which meant the removal of Solano López. Allied setback at Curupayty: their advance comes to a halt After the conference, the Allies marched into Paraguayan territory, reaching the defensive line of Curupayty. Trusting their numerical superiority and the possibility of attacking the flank of the defensive line through the Paraguay River by using the Brazilian ships, the Allies made a frontal assault on the defensive line, supported by the flank fire of the battleships.[57] However, the Paraguayans, commanded by general José E. Díaz, stood strong in their positions and set up for a defensive battle, inflicting tremendous damage on the attacking Allied troops, resulting in over 8,000 casualties on the Brazil-Argentine army against no more than 250 losses of the Paraguayans.[58] The Battle of Curupayty resulted in an almost catastrophic defeat for the Allied forces, ending their offensive for ten months, until July 1867.[16]: 65 The Allied leaders blamed each other for the disastrous failure at Curupayty. General Flores left for Uruguay in September 1866 shortly after the battle and was later murdered there in 1867. Porto Alegre and Tamandaré found common ground in their distaste for the Brazilian commander of the 1st Corps, field marshal Polidoro Jordão. General Jordão was ostracized for supporting Mitre and for being a member of the Conservative Party, while Porto Alegre and Tamandaré were Progressives.[59] General Porto Alegre also blamed Mitre for the tremendous defeat, saying:

Mitre had a harsh opinion of the Brazilians and said that "Porto Alegre and Tamandaré, who are cousins, and cousins even in lack of judgement have made a family pact to monopolize, in practice, the command of war." He further criticized Porto Alegre: "It is impossible to imagine a greater military nullity than this general, to which it can be added Tamandaré's dominating bad influence over him and the negative spirit of both in relation to the allies, owning to passions and petty interests."[59] Siege of HumaitáCaxias assumes command The Brazilian government decided to create a unified command over Brazilian forces operating in Paraguay and turned to the 63-year-old Luís Alves de Lima e Silva, the Marquess of Caxias, as the new leader on 10 October 1866.[61] Osório was sent to organize a 5,000-strong third corps of the Brazilian army in Rio Grande do Sul.[16]: 68 Caxias arrived in Itapiru on 17 November.[62] His first measure was to dismiss vice-admiral Tamandaré. The government had appointed Caxias' fellow Conservative vice-admiral Joaquim José Inácio—later the Viscount of Inhaúma—to lead the navy.[62] The Marquess of Caxias assumed command on 19 November.[63] He aimed to end the never-ending squabbling among the allied commanders and to increase his autonomy from the Brazilian government.[64] With the departure of president Mitre in February 1867, Caxias assumed overall command of the Allied forces.[16]: 65 He found the army practically paralyzed and devastated by disease. During this period Caxias trained his soldiers, re-equipped the army with new guns, improved the quality of the officer corps, and upgraded the health corps and overall hygiene of the troops, putting an end to epidemics.[65] From October 1866 until July 1867, all offensive operations were suspended.[66] Military operations were limited to skirmishes with the Paraguayans and bombarding Curupayty. Solano López took advantage of the disorganization of the enemy to reinforce the Fortress of Humaitá.[16]: 70 The advance resumes: fall of HumaitáAs the Brazilian army was ready for combat, Caxias sought to encircle Humaitá and force its capitulation by siege. To aid the war effort, Caxias used observation balloons to gather information of the enemy lines.[67] With the 3rd Corps ready for combat, the Allied army started its flanking march around Humaitá on 22 July.[67] The march to outflank the left-wing of the Paraguayan fortifications constituted the basis of Caxias' tactics. He wanted to bypass the Paraguayan strongholds, cut the connections between Asunción and Humaitá and finally encircle the Paraguayans. The 2nd Corps was stationed in Tuyutí, while the 1st corps and the newly created 3rd Corps were used by Caxias to encircle Humaitá.[68] President Mitre returned from Argentina and re-assumed overall command on 1 August.[69] With the capture on 2 November by Brazilian troops of the Paraguayan position of Tahí, at the shores of the river, Humaitá would become isolated from the rest of the country by land.[70][a]   The combined Brazilian, Argentine, and Uruguayan army continued advancing north through hostile territory to surround Humaitá. The Allied force advanced to San Solano on the 29th and Tayi on 2 November, isolating Humaitá from Asunción.[72] Before dawn on 3 November, Solano López reacted by ordering the attack on the rearguard of the allies in the Second Battle of Tuyutí.[16]: 73 The Paraguayans, commanded by general Bernardino Caballero breached the Argentine lines, causing enormous damage to the Allied camp and successfully capturing weapons and supplies, very needed by López for the war effort.[73] Only thanks to the intervention of Porto Alegre and his troops, the Allied army recovered.[74] During the Second Battle of Tuyutí, Porto Alegre fought with his saber in hand-to-hand combat and lost two horses.[75] In this battle, the Paraguayans lost over 2,500 men, while the allies had just over 500 casualties.[76] By 1867, Paraguay had lost 60,000 men to battle casualties, injuries, or disease. Due to the growing manpower shortage, López conscripted another 60,000 soldiers from slaves and children. Women were entrusted with all support functions alongside the soldiers. Many Paraguayan soldiers went into battle without shoes or uniforms. López enforced the strictest discipline, executing even his two brothers and two brothers-in-law for alleged defeatism.[77] By December 1867, there were 45,791 Brazilians, 6,000 Argentines and 500 Uruguayans at the front. After the death of Argentine vice president Marcos Paz, Mitre relinquished his position for the second and final time on 14 January 1868.[78] Allied representatives in Buenos Aires abolished the position of Allied commander-in-chief on 3 October, although the Marquess of Caxias continued to fill the role of Brazilian supreme commander.[79] On 19 February, Brazilian ironclads successfully made a passage up the Paraguay River under heavy fire, gaining full control of the river and isolating Humaitá from resupply by water.[80] Humaitá fell on 25 July 1868, after a long siege.[16]: 86 López with the bulk of his army escaped from the siege of Humaitá. Before doing so he tried a daring manoeuvre: to capture one or more allied ironclads by human wave boarding tactics. The assault on the warships Lima Barros and Cabral was a naval action that took place in the early hours of 2 March 1868, when Paraguayan canoes, joined two by two, disguised with branches and manned by 50 soldiers each, approached the ironclads Lima Barros and Cabral. The Imperial Fleet, which had already achieved the Passage of Humaitá, was anchored in the Paraguay river, before the Taji stronghold near Humaitá. Taking advantage of the dense darkness of the night and the hyacinths that descended on the current, a squadron of canoes covered by branches and foliage and tied two by two, crewed by 1,500 Paraguayans armed with machetes, hatchets and approaching swords, went to approach Cabral and Lima Barros. The fighting continued until dawn when the warships Brasil, Herval, Mariz e Barros and Silvado approached and shot the Paraguayans, who gave up the attack, losing 400 men and 14 canoes.[81] Fall of AsunciónEn route to Asunción, the Allied army went 200 kilometres (120 mi) north to Palmas, stopping at the Piquissiri River. There Solano López had concentrated 12,000 Paraguayans in a fortified line that exploited the terrain and supported the forts of Angostura and Itá-Ibaté. Resigned to frontal combat, Caxias ordered the so-called Piquissiri maneuver. While a squadron attacked Angostura, Caxias made the army cross to the west side of the river. He ordered the construction of a road in the swamps of the Gran Chaco along which the troops advanced to the northeast. At Villeta the army crossed the river again, between Asunción and Piquissiri, behind the fortified Paraguayan line.  Instead of advancing to the capital, already evacuated and bombarded, Caxias went south and attacked the Paraguayans from the rear in December 1868, in an offensive which became known as "Dezembrada".[16]: 89–91 Caxias' troops were ambushed while crossing the Ytororó during an initial advance, during which the Paraguayans inflicted severe damage on the Brazilian armies.[82] Days later, however, the Allies destroyed a whole Paraguayan division at the Battle of Avay.[16]: 94 Weeks later, Caxias won another decisive victory at the Battle of Lomas Valentinas and captured the last stronghold of the Paraguayan Army in Angostura. On 24 December, Caxias sent a note to Solano López asking for surrender, but Solano López refused and fled to Cerro León.[16]: 90–100 Alongside the Paraguayan president was the American Minister-Ambassador, Martin T. McMahon, who after the war became a fierce defender of López's cause.[83] Asunción was occupied on 1 January 1869, by Brazilian general João de Souza da Fonseca Costa, father of the future marshal Hermes da Fonseca. On 5 January, Caxias entered the city with the rest of the army.[16]: 99 Most of Caxias army settled in Asunción, where also 4,000 Argentine and 200 Uruguayan troops soon arrived together with about 800 soldiers and officers of the Paraguayan Legion. By this time, Caxias was ill and tired. On 17 January, he fainted during a mass; he relinquished his command the next day, and the day after that left for Montevideo.[84] Very soon the city hosted about 30,000 Allied soldiers; for the next few months these looted almost every building, including diplomatic missions of European nations.[84] Provisional government With Solano López on the run, the country lacked a government. Pedro II sent his foreign minister José Paranhos to Asunción where he arrived on 20 February 1869 and began consultations with the local politicians. Paranhos had to create a provisional government that could sign a peace accord and recognize the border claimed by Brazil between the two nations.[85] According to historian Francisco Doratioto, Paranhos, "the then-greatest Brazilian specialist on Platine affairs", had a "decisive" role in the installation of the Paraguayan provisional government.[86] With Paraguay devastated, the power vacuum resulting from Solano López's overthrow was quickly filled by emerging domestic factions which Paranhos had to accommodate. On 31 March, a petition was signed by 335 leading citizens asking Allies for a Provisional government. This was followed by negotiations between the Allied countries, which put aside some of the more controversial points of the Treaty of the Triple Alliance; on 11 June, agreement was reached with Paraguayan opposition figures that a three-man Provisional government would be established. On 22 July, a National Assembly met in the National Theatre and elected Junta Nacional of 21 men which then selected a five-man committee to select three men for the Provisional government. They selected Carlos Loizaga, Juan Francisco Decoud, and José Díaz de Bedoya. Decoud, being pro-Argentine, was unacceptable to Paranhos, who had him replaced with Cirilo Antonio Rivarola. The government was finally installed on 15 August but was just a front for the continued Allied occupation.[84] After the death of Lopez, the Provisional Government issued a proclamation on 6 March 1870 in which it promised to support political liberties, to protect commerce and to promote immigration. Loizaga and Bedoya were politically active members of the Paraguayan community in exile, both without any experience in public administration. Loizaga, specifically, was an old man who loved poetry and adventure stories and was tired and anxious to retire from public life.[citation needed] Bedoya was different, his brother was executed by Marshal Lopez for being a conspirator, and akin to his sibling he lacked education and was greedy.[citation needed] Later Bedoya made a trip to Buenos Aires and absconded with church silver from Paraguay (which had been given to him to serve as guarantee for a loan), and then disappeared from public life.[87] Rivarola was described as being devoted to the law but with arbitrary and despotic tendencies, both good and evil, possessing truth and falsehood, and a lack of character.[citation needed][neutrality is disputed] All three men were lackeys of the Empire of Brazil. Though there were other men more capable and available for the job, none had any chance of success without the patronage of the Allies.[neutrality is disputed] The Provisional Government did not last. Bedoya disappeared in May 1870; on 31 August 1870, Carlos Loizaga resigned. The remaining member, Cirilo Rivarola, was then immediately relieved of his duties by the National Assembly, which established a provisional Presidency, to which it elected Facundo Machaín, who assumed his post that same day. However, the next day, 1 September, he was overthrown in a coup that restored Rivarola to power, backed by Brazilian forces.[88] Guerilla warfareCampaign of the HillsThe son-in-law of Emperor Pedro II, Gaston, Count of Eu, was nominated in 1869 to direct the final phase of the military operations in Paraguay. At the head of 21,000 men, Eu led the campaign against the Paraguayan resistance, the Campaign of the Hills, which lasted over a year. Most important were the Battle of Piribebuy and the Battle of Acosta Ñu, in which more than 5,000 Paraguayans died.[89] After a successful beginning which included victories over the remnants of Solano López's army, the Count fell into depression and Paranhos became the unacknowledged, de facto commander-in-chief.[90] Death of Solano López President Solano López organized the resistance in the mountain range northeast of Asunción. At the end of the war, with Paraguay suffering severe shortages of weapons and supplies, Solano López reacted with draconian attempts to keep order, ordering troops to kill any of their colleagues, including officers, who talked of surrender.[91] Paranoia prevailed in the army, and soldiers fought to the bitter end in a resistance movement, resulting in more destruction in the country.[91] Two detachments were sent in pursuit of Solano López, who was accompanied by 200 men in the forests in the north. On 1 March 1870, the troops of General José Antônio Correia da Câmara surprised the last Paraguayan camp in Cerro Corá. During the ensuing battle, Solano López was wounded and separated from the remainder of his army. Too weak to walk, he was escorted by his aide and a pair of officers, who led him to the banks of the Aquidaban-nigui River. The officers left Solano López and his aide there while they looked for reinforcements. Before they returned, Câmara arrived with a small number of soldiers. Though he offered to permit Solano López to surrender and guaranteed his life, Solano López refused. Shouting "I die with my homeland!", he tried to attack Câmara with his sword. He was quickly killed by Câmara's men, bringing an end to the long conflict in 1870.[92][93] List of battlesCasualties of the war Paraguay suffered massive casualties, and the war's disruption and disease also cost civilian lives. Some historians estimate that the nation lost the majority of its population. The specific numbers are hotly disputed and range widely. A survey of 14 estimates of Paraguay's pre-war population varied between 300,000 and 1,337,000.[94] Later academic work based on demographics produced a wide range of estimates, from a possible low of 21,000 (7% of population) (Reber, 1988) to as high as 69% of the total prewar population (Whigham, Potthast, 1999). Because of the local situation, all casualty figures are a very rough estimate; accurate casualty numbers may never be determined. After the war, an 1871 census recorded 221,079 inhabitants, of which 106,254 were women, 28,746 were men, and 86,079 were children (with no indication of sex or upper age limit).[95] The worst reports are that up to 90% of the male population was killed, though this figure is without support.[91] One estimate places total Paraguayan losses—through both war and disease—as high as 1.2 million people, or 90% of its pre-war population,[96] but modern scholarship has shown that this number depends on a population census of 1857 that was a government invention.[97] A different estimate places Paraguayan deaths at approximately 300,000 people out of 500,000 to 525,000 pre-war inhabitants.[98] During the war, many men and boys fled to the countryside and forests. In the estimation of Vera Blinn Reber, however, "The evidence demonstrates that the Paraguayan population casualties due to the war have been enormously exaggerated".[99]  A 1999 study by Thomas Whigham from the University of Georgia and Barbara Potthast (published in the Latin American Research Review under the title "The Paraguayan Rosetta Stone: New Evidence on the Demographics of the Paraguayan War, 1864–1870", and later expanded in the 2002 essay titled "Refining the Numbers: A Response to Reber and Kleinpenning") used a methodology to yield more accurate figures. To establish the population before the war, Whigham used an 1846 census and calculated, based on a population growth rate of 1.7% to 2.5% annually (which was the standard rate at that time), that the immediately pre-war Paraguayan population in 1864 was approximately 420,000–450,000. Based on a census carried out after the war ended, in 1870–1871, Whigham concluded that 150,000–160,000 Paraguayan people had survived, of whom only 28,000 were adult males. In total, 60–70% of the population died as a result of the war,[100] leaving a woman/man ratio of 4 to 1 (as high as 20 to 1, in the most devastated areas).[100] For academic criticism of the Whigham-Potthast methodology and estimates see the main article Paraguayan War casualties.  Steven Pinker wrote that, assuming a death rate of over 60% of the Paraguayan population, this war was proportionally one of the most destructive in modern times for any nation state.[101][page needed] Allied lossesAs was common before antibiotics were developed, disease caused more deaths than war wounds. Bad food and poor sanitation contributed to disease among troops and civilians. Among the Brazilians, two-thirds of the dead died either in a hospital or on the march. At the beginning of the conflict, most Brazilian soldiers came from the north and northeast regions;[citation needed] the change from a hot to a colder climate, combined with restricted food rations, may have weakened their resistance. Entire battalions of Brazilians were recorded as dying after drinking water from rivers. Therefore, some historians believe cholera, transmitted in the water, was a leading cause of death during the war.[citation needed] Gender and ethnic aspectsWomen in the Paraguayan War Paraguayan women played a significant role in the Paraguayan War. During the period just before the war began many Paraguayan women were the heads of their households, meaning they held a position of power and authority. They received such positions by being widows, having children out of wedlock, or their husbands having worked as peons. When the war began women started to venture out of the home, becoming nurses, working with government officials, and establishing themselves into the public sphere. When The New York Times reported on the war in 1868, it considered Paraguayan women equal to their male counterparts.[102] Paraguayan women's support of the war effort can be divided into two stages. The first is from the time the war began in 1864 to the Paraguayan evacuation of Asunción in late 1868. During this period of the war, peasant women became practically the sole producers of agricultural goods.[103] The second stage begins when the war turned to a more guerrilla form; it started when the capital of Paraguay fell and ended with the death of Paraguay's president Francisco Solano López in 1870. At this stage, the number of women becoming victims of war was increasing.[citation needed] The government press, with doubtful veracity, claimed that battalions of women were formed to fight the Allies and exalted the role of Ramona Martínez (who was a woman enslaved by López) as "the American Joan of Arc" for her fighting and rallying of injured troops.[104] Women helped sustain Paraguayan society during a very unstable period. Though Paraguay did lose the war, the outcome might have been even more disastrous without women performing specific tasks. Women worked as farmers, soldiers, nurses, and government officials. They became a symbol for national unification, and at the end of the war, the traditions women maintained were part of what held the nation together.[105] A 2012 piece in The Economist argued that with the death of most of Paraguay's male population, the Paraguayan War distorted the sex ratio to women greatly outnumbering men and has impacted the sexual culture of Paraguay to this day. Because of the depopulation, men were encouraged after the war to have multiple children with multiple women, even supposedly celibate Catholic priests. A columnist linked this cultural idea to the paternity scandal of former president Fernando Lugo, who fathered multiple children while he was a supposedly celibate priest.[106] Paraguayan indigenous peoplePrior to the war, indigenous people occupied very little space in the minds of the Paraguayan elite. Paraguayan president Carlos Antonio Lopez even modified the country's constitution in 1844 to remove any mention of Paraguay's Hispano-Guarani character.[107] This marginalization was undercut by the fact that Paraguay had long prized its military as its only honorable and national institution and the majority of the Paraguayan military was indigenous and spoke Guarani. However, during the war, the indigenous people of Paraguay came to occupy an even larger role in public life, especially after the Battle of Estero Bellaco. For this battle, Paraguay put its "best" men, who happened to be of Spanish descent, front and center. Paraguay overwhelmingly lost this battle, as well as "the males of all the best families in the country."[108] The now remaining members of the military were "old men who had been left in Humaita, Indians, slaves and boys."[108] The war also bonded the indigenous people of Paraguay to the project of Paraguayan nation-building. In the immediate lead up to the war, they were confronted with a barrage of nationalist rhetoric (in Spanish and Guarani) and subject to loyalty oaths and exercises.[109] Paraguayan president Francisco Solano Lopez, son of Carlos Antonio Lopez, was well aware that the Guarani speaking people of Paraguay had a group identity independent of the Spanish-speaking Paraguayan elite. He knew he would have to bridge this divide or risk it being exploited by the 'Triple Alliance.' To a certain extent, Lopez succeeded in getting the indigenous people to expand their communal identity to include all of Paraguay. As a result of this, any attack on Paraguay was considered to be an attack on the Paraguayan nation, despite rhetoric from Brazil, Uruguay and Argentina saying otherwise. This sentiment increased after the terms of the Treaty of the Triple Alliance were leaked, especially the clause stating that Paraguay would pay for all the damages incurred by the conflict. Afro-Brazilians The Brazilian government allowed the creation of black-only units or "zuavos" in the military at the outset of the war, following the proposal of Afro-Brazilian Quirino Antônio do Espírito Santo, a veteran of the Brazilian War of Independence.[110] Over the course of the war, the zuavos became an increasingly attractive option for many enslaved Afro-Brazilian men, especially given the zuavos’ negative opinion toward slavery.[111] Once the zuavos had enlisted or forcibly recruited them, it became difficult for their masters to regain possession of them, since the government was desperate for soldiers.[111] By 1867, black-only units were no longer permitted, with the entire military being integrated just as it had been prior to the war. The overarching rationale behind this was that the "country needed recruits for its existing battalions, not more independently organized companies."[112] This did not mean the end of black soldiers in the Brazilian military. On the contrary, "impoverished gente de cor constituted the greater part of the soldiery in every Brazilian infantry battalion."[113] Afro-Brazilian women played a key role in sustaining the Brazilian military as "vivandeiras." Vivandeiras were poor women who traveled with the soldiers to undertake "logistic tasks such as carrying tents, preparing food and doing laundry."[114] For most of these women, the principal reason they became vivandeiras was because their male loved ones had joined as soldiers, and they wanted to take care of them. However, the Brazilian government actively worked to minimize the importance of their work by labeling it "service to their male kin, not the nation" and considering it to be "natural" and "habitual."[114] The reality was that the government depended heavily on these women and officially required their presence in the camps.[114] Poor Afro-Brazilian women also served as nurses, with most of them being trained upon entry into the military to assist male doctors in the camps. These women were "seeking gainful employment to compensate for the loss of income from male kin who had been drafted into the war."[114] Territorial changes and treaties Paraguay permanently lost its claim to territories which, before the war, were in dispute between it and Brazil or Argentina, respectively. In total, about 140,000 square kilometres (54,000 sq mi) were affected. Those disputes had been longstanding and complex. Disputes with BrazilIn colonial times certain lands lying to the north of the River Apa were in dispute between the Portuguese Empire and the Spanish Empire. After independence they continued to be disputed between the Empire of Brazil and the Republic of Paraguay.[115] After the war Brazil signed a separate Loizaga–Cotegipe Treaty of peace and borders with Paraguay on 9 January 1872, in which it obtained freedom of navigation on the Paraguay River. Brazil also retained the northern regions it had claimed before the war.[116] Those regions are now part of its State of Mato Grosso do Sul. Disputes with ArgentinaMisionesIn colonial times the missionary Jesuits established numerous villages in lands between the rivers Paraná and Uruguay. After the Jesuits were expelled from Spanish territory in 1767, the ecclesiastical authorities of both Asunción and Buenos Aires made claim to religious jurisdiction in these lands and the Spanish government sometimes awarded it to one side, sometimes to the other; sometimes they split the difference. After independence, the Republic of Paraguay and the Argentine Confederation succeeded to these disputes.[117] On 19 July 1852, the governments of the Argentine Confederation and Paraguay signed a treaty, by which Paraguay relinquished its claim to the Misiones.[118] However, this treaty did not become binding, because it required to be ratified by the Argentine Congress, which refused.[119] Paraguay's claim was still alive on the eve of the war. After the war the disputed lands definitively became the Argentine national territory of Misiones, now Misiones Province. Gran ChacoThe Gran Chaco is an area lying to the west of the River Paraguay. Before the war it was "an enormous plain covered by swamps, chaparral and thorn forests ... home to many groups of feared Indians, including the Guaicurú, Toba and Mocoví."[119] There had long been overlapping claims to all or parts of this area by the Argentine Confederation, Bolivia and Paraguay. With some exceptions, these were paper claims, because none of those countries was in effective occupation of the area: essentially, they were claims to be the true successor to the Spanish Empire, in an area never effectively occupied by Spain itself, and wherein Spain had no particular motive for prescribing internal boundaries. The exceptions were as follows. First, to defend itself against Indian incursions, both in colonial times and after, the authorities in Asunción had established some border forts on the west bank of the river Paraguay—a coastal strip within the Chaco. By the same treaty of 19 July 1852, between Paraguay and the Argentine Confederation, an undefined area in the Chaco north of the Bermejo River was implicitly conceded to belong to Paraguay. As already stated, the Argentine Congress refused to ratify this treaty; and it was protested by the government of Bolivia as inimical to its own claims. The second exception was that in 1854, the government of Carlos Antonio López established a colony of French immigrants on the right bank of the River Paraguay at Nueva Burdeos; when it failed, it was renamed Villa Occidental.[120] After 1852, and more especially after the State of Buenos Aires rejoined the Argentine Confederation, Argentina's claim to the Chaco hardened; it claimed territory all the way up to the border with Bolivia. By Article XVI of the Treaty of the Triple Alliance Argentina was to receive this territory in full. However, the Brazilian government disliked what its representative in Buenos Aires had negotiated in this respect and resolved that Argentina should not receive "a handsbreadth of territory" above the Pilcomayo River. It set out to frustrate Argentina's further claim, with eventual success. The post-war border between Paraguay and Argentina was resolved through long negotiations, completed 3 February 1876, by signing the Machaín-Irigoyen Treaty. This treaty granted Argentina roughly one third of the area it had originally desired. Argentina became the strongest of the River Plate countries. When the two parties could not reach consensus on the fate of the Chaco Boreal area between the Río Verde and the main branch of Río Pilcomayo, the President of the United States, Rutherford B. Hayes, was asked to arbitrate. His award was in Paraguay's favor. The Paraguayan Presidente Hayes Department is named in his honor. Consequences of the warParaguayThere was a destruction of the pre-war state structure, a definitive loss of claimed frontier territories, and the ruination of the Paraguayan economy, so that even decades later, it could not develop in the same way as its neighbors. Paraguay is estimated to have lost up to 69% of its population, most of them due to illness, hunger and physical exhaustion, of which 90% were male according to the most extreme reports, and also maintained a high debt of war with the allied countries that, not completely paid, ended up being pardoned in 1943 by the Brazilian President Getúlio Vargas. A new pro-Brazil government was installed in Asunción in 1869, while Paraguay remained occupied by Brazilian and Argentine forces until 1876, when the border treaty between Paraguay and Argentina was concluded with American arbitration, guaranteeing Paraguay's sovereignty and leaving it a buffer state between its larger neighbors. Brazil The War helped the Brazilian Empire to reach its peak of political and military influence, becoming the Great Power of South America, and also helped to bring about the end of slavery in Brazil, moving the military into a key role in the public sphere.[121] However, the war caused a ruinous increase of public debt, which took decades to pay off, severely limiting the country's growth. The war debt, alongside a long-lasting social crisis after the conflict,[122][123] are regarded as crucial factors for the fall of the Empire and proclamation of the First Brazilian Republic.[124][125] During the war the Brazilian army took complete control of Paraguayan territory and occupied the country for six years after 1870. In part this was to prevent the annexation of even more territory by Argentina, which had wanted to seize the entire Chaco region. During this time, Brazil and Argentina had strong tensions, with the threat of armed conflict between them. During the wartime sacking of Asunción, Brazilian soldiers carried off war trophies. Among the spoils taken was a large caliber gun called Cristiano, named because it was cast from church bells of Asunción melted down for the war. In Brazil the war exposed the fragility of the Empire and dissociated the monarchy from the army. The Brazilian army became a new and influential force in national life. It developed as a strong national institution that, with the war, gained tradition and internal cohesion. The Army would take a significant role in the later development of the history of the country. The economic depression and the strengthening of the army later played a large role in the deposition of the emperor Pedro II and the republican proclamation in 1889. Marshal Deodoro da Fonseca became the first Brazilian president. As in other countries, "wartime recruitment of slaves in the Americas rarely implied a complete rejection of slavery and usually acknowledged masters' rights over their property."[126] Brazil compensated owners who freed slaves for the purpose of fighting in the war, on the condition that the freedmen immediately enlist. It also impressed slaves from owners when needing manpower, and paid compensation. In areas near the conflict, slaves took advantage of wartime conditions to escape, and some fugitive slaves volunteered for the army. Together these effects undermined the institution of slavery. But the military also upheld owners' property rights, as it returned at least 36 fugitive slaves to owners who could satisfy its requirement for legal proof. Significantly, slavery was not officially ended until the 1880s.[126] Brazil spent close to 614,000 réis (the Brazilian currency at the time), which were gained from the following sources:

Due to the war, Brazil ran a deficit between 1870 and 1880, which was finally paid off. At the time foreign loans were not significant sources of funds.[127] ArgentinaFollowing the war, Argentina faced many federalist revolts against the national government. Economically it benefited from having sold supplies to the Brazilian army, but the war overall decreased the national treasure. The national action contributed to the consolidation of the centralized government after revolutions were put down, and the growth in influence of Army leadership. It has been argued the conflict played a key role in the consolidation of Argentina as a nation-state.[128] That country became one of the wealthiest in the world, by the early 20th century.[129] It was the last time that Brazil and Argentina openly took such an interventionist role in Uruguay's internal politics.[130] By the account of historian Mateo Martinic the war put a temporary hold on Argentine plans to challenge the Chilean occupation of the Strait of Magellan.[131] UruguayUruguay suffered lesser effects, although nearly 5,000 soldiers were killed. As a consequence of the war, the Colorados gained political control of Uruguay and, despite rebellions, retained it until 1958. Modern interpretations of the warInterpretation of the causes of the war and its aftermath has been a controversial topic in the histories of participating countries, especially in Paraguay. There it has been considered either a fearless struggle for the rights of a smaller nation against the aggression of more powerful neighbors, or a foolish attempt to fight an unwinnable war that almost destroyed the nation. Several revisionist historians consider the mass extermination of the Paraguayan people during the war to be a case of genocide.[132][133] In 2022, the Mercosur Parliament formed the Sub-Commission for Truth and Justice on the War of the Triple Alliance, within its Human Rights Commission, to investigate the potential crimes (including genocide) committed during the war and then arrive at a "consensual truth" on the matter within the parliament.[134] In December 1975, after presidents Ernesto Geisel of Brazil and Alfredo Stroessner of Paraguay signed a treaty of friendship and co-operation[135] in Asunción, the Brazilian government returned some of its spoils of war to Paraguay but has kept others. In April 2013 Paraguay renewed demands for the return of the "Christian" cannon. Brazil has had this on display at the former military garrison, now used as the National History Museum, and says that it is part of its history as well.[136] Theories about British influence on the outbreak of warA popular belief among Paraguayans and Argentine revisionists since the 1960s contends that the outbreak of war was due to the machinations of the British government, a theory which historians have noted has little to no basis in historical evidence. In Brazil, some have claimed that the United Kingdom was the primary source of financing for the Triple Alliance during the war, with British aid being given in order to advance Britain's economic interests in the region; something which historians have noted that has little evidence to support it as well; noting that from 1863 to 1865 Brazil and Great Britain were engaged in a diplomatic incident, and five months after the outbreak of the Paraguayan war the two countries temporarily broke off relations. They have also noted that in 1864, a British diplomat wrote a letter to Solano López asking him to avoid initiating hostilities in the region, and there remains no evidence that Britain "forced" the allies to attack Paraguay.[137] Some left-wing historians of the 1960s and 1970s (most notably Eric Hobsbawm in his work "The Age of Capital: 1848–1875") claimed that the Paraguayan War broke out as a result of British influence on the continent,[138][139] claiming that as Britain needed a new source of cotton during the American Civil War (as the blockaded American South had been their main cotton supplier before the war).[140] Right wing and even far-right wing historians, especially from Argentina and Paraguay, have also claimed that British influence was a major reason for the outbreak of war.[141][142][143] Noteworthy is the fact that both the Great Soviet Encyclopedia and the Great Russian Encyclopedia, considered as official sources of the USSR and the Russian Federation respectively, also claim that the British Empire had much to do for sustaining the war effort and finances of the "Triple Alliance" against Paraguay. A document which has been used to support this claim is a letter from Edward Thornton (Minister of Great Britain in the Plate Basin) to British Prime Minister Lord John Russell, which contained the following statement:

Charles Washburn, who was the Minister of the United States to Paraguay and Argentina, claimed that Thornton spoke of Paraguay, months before the outbreak of the conflict, as:

However, historian E.N. Tate noted that:

Other historians have also disputed the claims of British influence in the outbreak of war, pointing out that there is no documented evidence for it.[148][137][149] They note that, although the British economy and commercial interests benefited from the war, the British government opposed it from the start. In addition, they also noted that the war damaged international commerce (including Britain's), and the British government disapproved of the secret clauses in the Treaty of the Triple Alliance.[150] Britain at the time already was increasing their imports of Egyptian and Indian cotton and as such did not need any from Paraguay.[151][152] William Doria (the British Chargé d'Affaires in Paraguay who briefly acted in Thornton's place), joined French and Italian diplomats in condemning Argentina's President Bartolomé Mitre's involvement in Uruguay. But when Thornton returned to the job in December 1863, Doria threw his full backing behind Mitre.[153] Effects on yerba mate industrySince colonial times, yerba mate had been a major cash crop for Paraguay. Until the war, it had generated significant revenues for the country. The war caused a sharp drop in harvesting of yerba mate in Paraguay, reportedly by as much as 95% between 1865 and 1867.[154] Soldiers from all sides used yerba mate to diminish hunger pangs and alleviate combat anxiety.[155] Much of the 156,415 square kilometers (60,392 sq mi) lost by Paraguay to Argentina and Brazil was rich in yerba mate, so by the end of the 19th century, Brazil became the leading producer of the crop.[155] Foreign entrepreneurs entered the Paraguayan market and took control of its remaining yerba mate production and industry.[154] NotesReferences

Bibliography

External links

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||