|

Jeconiah

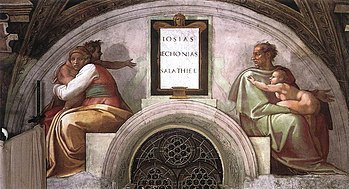

Jeconiah (Hebrew: יְכָנְיָה Yəḵonəyā [jəxɔnjaː], meaning "Yah has established";[2] Greek: Ἰεχονίας; Latin: Iechonias, Jechonias), also known as Coniah[3] and as Jehoiachin (Hebrew: יְהוֹיָכִין Yəhōyāḵīn [jəhoːjaːˈxiːn]; Latin: Ioachin, Joachin), was the nineteenth and penultimate king of Judah who was dethroned by the King of Babylon, Nebuchadnezzar II in the 6th century BCE and was taken into captivity. He was the son and successor of King Jehoiakim, and the grandson of King Josiah. Most of what is known about Jeconiah is found in the Hebrew Bible. Records of Jeconiah's existence have been found in Iraq, such as the Jehoiachin's Rations Tablets. These tablets were excavated near the Ishtar Gate in Babylon and have been dated to c. 592 BCE. Written in cuneiform, they mention Jeconiah (Akkadian: 𒅀𒀪𒌑𒆠𒉡, Yaʾúkinu [ia-ʾ-ú-ki-nu]) and his five sons as recipients of food rations in Babylon.[4] Jeconiah in scriptureReign Jeconiah reigned three months and ten days, beginning December 9, 598 BCE. He succeeded Jehoiakim as king of Judah after raiders from surrounding lands invaded Jerusalem and killed his father.[5] It is likely that the king of Babylon was behind this effort, as a response to Jehoiakim's revolt, starting sometime after 601 BCE. Three months and ten days after Jeconiah became king, the armies of Nebuchadnezzar II seized Jerusalem, with the intention to take high class Judahite captives and assimilate them into Babylonian society. On March 15/16th, 597 BCE, Jeconiah, his entire household and three thousand Jews were exiled to Babylon.[6][7][8]: 217 The Masoretic Text of 2 Chronicles 36 states that Jeconiah's rule began at the age of eight, while in 2 Kings 24:8 Jeconiah is said to have come to the throne at eighteen.[9][10] Modern scholars have treated the difference between "eight" and "eighteen" as reflecting a copying error on one side or the other of the issue.[11] During exileAfter Jeconiah was deposed as king, his uncle Zedekiah (2 Kings 24:17) was appointed by Nebuchadnezzar to rule Judah. Zedekiah was the son of Josiah.[12] Jeconiah would later be regarded as the first of the exilarchs. In the Book of Ezekiel, the author refers to Jeconiah as king and dates certain events by the number of years he was in exile. The author identifies himself as Ezekiel, a contemporary of Jeconiah, and he never mentions Zedekiah by name.[13] Release from captivityAccording to 2 Kings 25:27–30, Jeconiah was released from prison "in the 37th year of the exile", in the year that Amel-Marduk (Evil-Merodach) came to the throne, and given a prestigious position at court. Jeconiah's release in Babylon brings to a close the Books of Kings and the Deuteronomistic history. Babylonian records show that Amel-Marduk began his reign in October 562 BCE.[14] According to Jeremiah 52:31, Jeconiah was released from prison "in the twelfth month, on the twenty-fifth day of the month": this indicates the first year of captivity to be 598/597 BCE, according to Judah's Tishri-based calendar. The 37th year of captivity was thus, by Judean reckoning, the year that began in Tishri of 562, consistent with the synchronism to the accession year of Amel-Marduk given in Babylonian records. CurseJeremiah (22:28–30) cursed Jeconiah that none of his descendants would ever sit on the throne of Israel:

Chapter 1, verses 11–12 of the Gospel of Matthew lists Jeconiah in the lineage of Jesus Christ, through Joseph. If Joseph was the biological father of Jesus (contrary to Christian belief), then Jesus could not rightfully claim to be the Messiah as the curse of Jeconiah, if true, would apply to Him. Richard Challoner interpreted the two genealogies of Matthew and Luke to be referring to a biological offspring and an offspring from a Levirate marriage. According to this concept, Joseph may have been a biological descendant from Jeconiah, but within Jewish law he would have been counted as a descendant of someone else due to the carrying of a brother's name through the Levirate marriage. In Rabbinical literatureJehoiachin was made king in place of his father by Nebuchadnezzar; but the latter had hardly returned to Babylon when some one said to him, "A dog brings forth no good progeny," whereupon he recognized that it was poor policy to have Jehoiachin for king (Lev. R. xix. 6; Seder 'Olam R. xxv.). In Daphne, near Antiochia, Nebuchadnezzar received the Great Sanhedrin, to whom he announced that he would not destroy the Temple if the king were delivered up to him. When the king heard this resolution of Nebuchadnezzar he went upon the roof of the Temple, and, turning to heaven, held up the Temple keys, saying: "As you no longer consider us worthy to be your ministers, take the keys that you have entrusted to us until now." Then a miracle happened; for a fiery hand appeared and took the keys, or, as others say, the keys remained suspended in the air where the king had thrown them (Lev. R. l.c.; Yer. Sheḳ. vi. 50a; other versions of the legend of the keys are given in Ta'an. 29a; Pesiḳ. R. 26 [ed. Friedmann, p. 131a], and Syriac Apoc. Baruch, x. 18). The king as well as all the scholars and nobles of Judah were then carried away captive by Nebuchadnezzar (Seder 'Olam R. l.c.; compare Ratner's remark ad loc.). According to Josephus, Jehoiachin gave up the city and his relatives to Nebuchadnezzar, who took an oath that neither they nor the city should be harmed. But the Babylonian king broke his word; for scarcely a year had elapsed when he led the king and many others into captivity. Jehoiachin's sad experiences changed his nature entirely, and as he repented of the sins which he had committed as king he was pardoned by God, who revoked the decree to the effect that none of his descendants should ever become king (Jer. xxii. 30; Pesiḳ., ed. Buber, xxv. 163a, b); he even became the ancestor of the Messiah (Tan., Toledot, 20 [ed. Buber, i. 140]). It was especially his firmness in fulfilling the Law that restored him to God's favor. He was kept by Nebuchadnezzar in solitary confinement, and as he was therefore separated from his wife, the Sanhedrin, which had been expelled with him to Babylon, feared that at the death of this queen the house of David would become extinct. They managed to gain the favor of Queen Semiramis, who induced Nebuchadnezzar to ameliorate the lot of the captive king by permitting his wife to share his prison. As he then manifested great self-control and obedience to the Law, God forgave him his sins (Lev. R. xix., end). Jehoiachin lived to see the death of his conqueror, Nebuchadnezzar, which brought him liberty; for within two days of his father's death Evil-merodach opened the prison in which Jehoiachin had languished for so many years. Jehoiachin's life is the best illustration of the maxim, "During prosperity a man must never forget the possibility of misfortune; and in adversity must not despair of prosperity's return" (Seder 'Olam R. xxv.). On the advice of Jehoiachin, Nebuchadnezzar's son cut his father's body into 300 pieces, which he gave to 300 vultures, so that he could be sure that Nebuchadnezzar would never return to worry him ("Chronicles of Jerahmeel," lxvi. 6). Evil-merodach treated Jehoiachin as a king, clothed him in purple and ermine, and for his sake liberated all the Jews that had been imprisoned by Nebuchadnezzar (Targ. Sheni, near the beginning). It was Jehoiachin, also, who erected the magnificent mausoleum on the grave of the prophet Ezekiel (Benjamin of Tudela, "Itinerary," ed. Asher, i. 66). In the Second Temple there was a gate called "Jeconiah's Gate," because, according to tradition, Jeconiah (Jehoiachin) left the Temple through that gate when he went into exile (Mid. ii. 6).[15] GenealogyJeconiah was the son of Jehoiakim and Nehushta, the daughter of Elnathan of Jerusalem.[16] He had eight children: Assir, Shealtiel, Malkiram, Pedaiah, Shenazzar, Jekamiah, Hoshama and Nedabiah. (1 Chronicles 3:17–18). Jeconiah is also mentioned in the first book of Chronicles as the father of Pedaiah, who in turn was the father of Zerubbabel. A list of his descendants is given in 1 Chronicles 3:17–24. In listing the genealogy of Jesus Christ, Matthew 1:11 records Jeconiah the son of Josiah as an ancestor of Joseph, the husband of Mary. This Jeconiah is uncle of Jeconiah son of Jehoiakim (1 Chron 3:16), which the Jeconiah/Jehoiakim lineage was cursed (Jer 22:24,30). The Jeconiah/Josiah (Matt 1:11) lineage to Jesus is not cursed. Dating Jeconiah's reign The Babylonian Chronicles establish that Nebuchadnezzar captured Jerusalem for the first time on 2 Adar (16 March) 597 BCE.[17] Before Wiseman's publication of the Babylonian Chronicles in 1956, Thiele had determined from biblical texts that Nebuchadnezzar's initial capture of Jerusalem and its king Jeconiah occurred in the spring of 597 BCE, whereas Kenneth Strand points out that other scholars, including Albright, more frequently dated the event to 598 BCE.[18]: 310, 317 Thiele's datesThiele said that the 25th anniversary of Jeconiah's captivity was April 25 (10 Nisan), 573 BCE, implying that he began the exile to Babylon on 10 Nisan 597, 24 years earlier. His reasoning in arriving at this exact date was based on Ezekiel 40:1, where Ezekiel, without naming the month, says it was the tenth day of the month, "on that very day." Since this fits with his idea that Jeconiah's (and Ezekiel's) exile to Babylon began a month later than the capturing of the city, thus allowing a new Nisan-based year to begin, Thiele took these words in Ezekiel as referring to the day in which the captivity or exile proper began. He therefore ended Jehoiachin's reign of three months and ten days on this date. The dates he gives for Jeconiah's reign are then: 21 Heshvan (9 December) 598 BCE to 10 Nisan (22 April) 597 BCE.[18]: 187 Thiele's reasoning in this regard has been criticized by Rodger C. Young, who advocates the 587 date for the fall of Jerusalem.[19][20] Young argues that Thiele's arithmetic is inconsistent, and adds an alternative explanation of the phrase "on that very day" (be-etsem ha-yom ha-zeh) in Ezekiel 40:1. This phrase is used three times in Leviticus 23:28–30 to refer the Day of Atonement, always observed on the tenth of Tishri, and Ezekiel's writings in several places show familiarity with the Book of Leviticus.[20]: 121, n. 7 A further argument in favor of this interpretation is that in the same verse, Ezekiel says it was Rosh Hashanah (New Year's Day) and also the tenth of the month, indicating the start of a Jubilee year, since only in a Jubilee year did the year begin on the tenth of Tishri, the Day of Atonement (Leviticus 25:9). The Talmud (tractate Arakin 12a,b) and the Seder Olam (chapter 11) also say that Ezekiel saw his vision at the beginning of a Jubilee year, the 17th, consistent with this interpretation of Ezekiel 40:1. Because this offers an alternative explanation to Thiele's interpretation of Ezekiel 40:1, and because Thiele's chronology for Jeconiah is incompatible with the records of the Babylonian Chronicle, the infobox below dates the end of Jeconiah's reign to 2 Adar (16 March) 597 BCE, the date of the first capture of Jerusalem as given in the Babylonian records. Thiele's dates for Jeconiah, however, and his date of 586 BCE for the fall of Jerusalem, continue to hold considerable weight with the scholarly community.[21][22] However, no such complication[clarification needed] is necessary since the tenth of Tishri 574 BCE is precisely as stated in Ezekiel 40:1, both in the fourteenth year of the Temple's destruction in 587 BCE and the twenty-fifth year of Jeconiah's exile in 597 BCE.[23] Gershon Galil also attempted to reconcile a 586 date for the fall of Jerusalem with the data for Jeconiah's exile. Like Thiele, he assumed that the years of exile should be measured from Nisan, but for a different reason. Galil hypothesized that Israel’s calendar was one month ahead of that of Babylon because Babylon had inserted an intercalary month and Israel had not yet done so.[24] This would make Adar (the twelfth month) in the Babylonian records correspond to Nisan (the first month) in Judean counting. But this hypothesis, like Thiele's, runs into difficulty with Ezekiel 40:1, since the 25th year of captivity would begin in Nisan of 573 and the fall of Jerusalem, 14 years earlier, would be in 587, not the 586 that Galil and Thiele advocate. There is further conflict with the Babylonian data, because the 37th year of captivity, the year in which Jeconiah was released from prison, would be the year starting in Nisan of 561 BCE, not Nisan of 562 BCE as given in the Babylonian Chronicle. Recognizing these conflicts, Galil admits (p. 377) that his date for the fall of Jerusalem (586 BCE) is inconsistent with the precise data given in the Bible and the Babylonian Chronicle. Dating the fall of Jerusalem using Jeconiah's dating The reign of Jeconiah is considered important in establishing the chronology of events in the early sixth century BCE in the Middle East. This includes resolving the date of the fall of Jerusalem to Nebuchadnezzar. According to Jeremiah 52:6, the city wall was breached in the summer month of Tammuz in the eleventh year of Zedekiah. Historians, however, have been divided on whether the year was 587 or 586 BCE. A 1990 study listed eleven scholars who preferred 587 and eleven who preferred 586.[25] The Babylonian records of the second capture of Jerusalem have not been found, and scholars looking at the chronology of the period must rely on the Biblical texts, as correlated with extant Babylonian records from before and after the event. In this regard, the Biblical texts regarding Jeconiah are especially important, because the time of his reign in Jerusalem was fixed by Donald Wiseman's 1956 publication, and this is consistent with his thirty-seventh year of captivity overlapping the accession year of Amel-Marduk, as mentioned above. Ezekiel's treatment of Jeconiah's dates are a starting point for determining the date of the fall of Jerusalem. He dated his writings according to the years of captivity he shared with Jeconiah, and he mentions several events related to the fall of Jerusalem in those writings. In Ezekiel 40:1, Ezekiel dates his vision to the 25th year of the exile and fourteen years after the city fell. If Ezekiel and the author of 2 Kings 25:27 were both using Tishri-based years, the 25th year would be 574/573 BCE and the fall of the city, 14 years earlier, would be in 588/587—i.e., in the summer of 587 BCE. This is consistent with other texts in Ezekiel related to the fall of the city. Ezekiel 33:21 relates that a refugee arrived in Babylon and reported the fall of Jerusalem in the twelfth year, tenth month of "our exile." Measuring from the first year of exile, 598/597, this was January of 586 BCE, incompatible with Jerusalem falling in the summer of 586 BCE, but consistent with its fall in the summer of 587 BCE. The other side holds that since Jeconiah surrendered in March 597, January 586 is less than eleven years later and therefore can not be considered in the twelfth year of the exile. Thiele held to a 586 BCE date for the capture of Jerusalem and the end of Zedekiah's reign. Recognizing to some extent the importance of Ezekiel's measuring time by the years of captivity of Jeconiah, and in particular the reference to the 25th year of that captivity in Ezekiel 40:1, he wrote,

In order to justify his 586 date, Thiele had assumed that the years of captivity for Jeconiah must be calendar years starting in Nisan, in contrast to the Tishri-based years that he used everywhere else for the kings of Judah. He also assumed that Jeconiah's captivity or exile was not to be measured from Adar of 597 BCE, the month Nebuchadnezzar captured Jerusalem and its king according to the Babylonian Chronicle, but in the next month, Nisan, when Thiele assumed Jeconiah began the trip to Babylon. Granting these assumptions, the first year of captivity would be the year starting in Nisan of 597 BCE. The twenty-fifth year of captivity would start in Nisan of 573 BCE, (573/572) twenty-four years later. Years of captivity must be measured in this non-accession sense (the year in which the captivity started was considered year one of the captivity), otherwise the 37th year of captivity, the year in which Jeconiah was released from prison, would start on Nisan 1 of 560 BCE (597 − 37), two years after the accession year of Amel-Marduk, according to the dating of his accession year that can be fixed with exactitude by the Babylonian Chronicle. Thiele then noted that Ezekiel 40:1 says that this 25th year of captivity was 14 years after the city fell. Fourteen years before 573/572 is 587/586, and since Thiele is assuming Nisan years for the captivity, this period ended the day before Nisan 1 of 586. But this is three months and nine days before Thiele's date for the fall of the city on 9 Tammuz 586 BCE. Even Thiele's assumption that the years of captivity were measured from Nisan does not reconcile Ezekiel's chronology for the captivity of Jeconiah with a 586 date, and the calculation given above that uses the customary Tishri-based years yields the summer of 587, consistent with all other texts in Ezekiel related to Jeconiah's captivity. Another text in Ezekiel offers a clue to why there has been such a conflict over the date of Jerusalem's fall in the first place. Ezekiel 24:1–2 (NIV) records the following:

Assuming that dating here is according to the years of exile of Jeconiah, as elsewhere in Ezekiel, the Babylonian siege of Jerusalem began on January 27, 589 BCE.[26] This can be compared to a similar passage in 2 Kings 25:1 (NIV):

The ninth year, tenth month, tenth day in Ezekiel is identical to the period in 2 Kings. In Ezekiel, the years are everywhere else measured according to Jeconiah's captivity, which must be taken in a non-accession sense, so that the beginning of the siege was eight actual years after the beginning of the captivity. The comparison with 2 Kings 25:1 would indicate that Zedekiah's years in 2 Kings were also by non-accession reckoning. His eleventh year, the year in which Jerusalem fell, would then be 588/587 BCE, in agreement with all texts in Ezekiel and elsewhere that are congruent with that date. Some who maintain the 586 date therefore maintain that in this one instance, Ezekiel, without explicitly saying so, switched to the regnal years of Zedekiah, although Ezekiel apparently regarded Jeconiah as the rightful ruler and never names Zedekiah in his writing. Another view is that a later copyist, aware of the 2 Kings passage, modified it and inserted it into the text of Ezekiel. In his study of all biblical texts related to the Babylonian capture of Jerusalem, Young concludes that these conjectures are not necessary, and that all texts related to the fall of Jerusalem in Jeremiah, Ezekiel, 2 Kings, and 2 Chronicles are internally consistent and consistent with the fall of the city in Tammuz of 587 BCE.[27] Archeological findingsDuring his excavation of Babylon in 1899–1917, Robert Koldewey discovered a royal archive room of King Nebuchadnezzar near the Ishtar Gate. It contained tablets dating to 595–570 BCE. The tablets were translated in the 1930s by the German Assyriologist, Ernst Weidner. Four of these tablets list rations of oil and barley given to various individuals—including the deposed King Jehoiachin—by Nebuchadnezzar from the royal storehouses, dated five years after Jehoiachin was taken captive. One tablet reads:

Another reads:

The Babylonian Chronicles are currently housed in the Pergamum Museum in Berlin. See also

References

External links

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||