Kino-Eye

|

Read other articles:

Artikel ini perlu diwikifikasi agar memenuhi standar kualitas Wikipedia. Anda dapat memberikan bantuan berupa penambahan pranala dalam, atau dengan merapikan tata letak dari artikel ini. Untuk keterangan lebih lanjut, klik [tampil] di bagian kanan. Mengganti markah HTML dengan markah wiki bila dimungkinkan. Tambahkan pranala wiki. Bila dirasa perlu, buatlah pautan ke artikel wiki lainnya dengan cara menambahkan [[ dan ]] pada kata yang bersangkutan (lihat WP:LINK untuk keterangan lebih lanjut). …

Peta Amerika Serikat yang menunjukkan 50 negara bagiannya beserta Distrik Columbia Amerika Serikat adalah sebuah republik federal[1] yang terdiri dari 50 negara bagian, sebuah distrik federal, lima teritorial besar, dan berbagai kepulauan kecil.[2][3] 48 negara bagian di daratan utama dan Distrik Columbia, berada di tengah Amerika Utara antara Kanada dan Meksiko; dua negara bagian lainnya, Alaska dan Hawaii, masing-masing berada di bagian barat laut Amerika Utara dan sebu…

The Princess and the FrogPoster layar lebarSutradaraRon ClementsJohn MuskerProduserPeter Del VechoJohn LasseterDitulis olehRon ClementsJohn MuskerRob EdwardsPemeranAnika Noni RoseOprah WinfreyKeith DavidJenifer LewisJohn GoodmanBruno CamposTerrence HowardPenata musikRandy NewmanPenyuntingJeff DraheimDistributorWalt Disney PicturesTanggal rilis11 Desember 2009 (Amerika Serikat)[1]6 Januari 2010 (Indonesia)Negara Amerika SerikatBahasaInggris The Princess and the Frog adalah film…

Former dam in Los Angeles County, California, US Dam in Los Angeles County, CaliforniaVan Norman DamsAn oblique aerial view of the Lower Van Norman Dam, taken after the February 9, 1971 San Fernando EarthquakeCountryUnited StatesLocationLos Angeles County, CaliforniaCoordinates34°17′10″N 118°28′47″W / 34.2862°N 118.4796°W / 34.2862; -118.4796PurposeWater supplyStatusDecommissionedConstruction began1919; 105 years ago (1919)(upper dam)191…

City in Utah, United States For other uses, see Manti (disambiguation). City in Utah, United StatesManti, UtahCityBirdseye view of Manti and the Sanpete Valley, August 2004Location in Sanpete County and the state of Utah.Coordinates: 39°15′53″N 111°38′20″W / 39.26472°N 111.63889°W / 39.26472; -111.63889CountryUnited StatesStateUtahCountySanpeteFounded1849Incorporated1851Founded byGeorge Washington Bradley and Isaac MorleyNamed forA city in the Book of MormonGo…

حسين عبده مناصب رئيس هيئة قضايا الدولة في المنصب1 يوليو 2017 – 24 أغسطس 2019 معلومات شخصية اسم الولادة حسين عبده خليل حمزة الميلاد 24 أغسطس 1949 أبريم الوفاة 6 أغسطس 2022 (72 سنة) [1] أسوان مواطنة المملكة المصرية (1949–1952) جمهورية مصر (1953–1958) الجمهورية العربية ال�…

Secondary school in Kingston, Ontario, CanadaQueen Elizabeth Collegiate and Vocational InstituteAddress145 Kirkpatrick StreetKingston, Ontario, K7K 2P4CanadaCoordinates44°15′13″N 76°30′07″W / 44.25361°N 76.50194°W / 44.25361; -76.50194InformationSchool typeSecondaryMottoVeritas Liberat(The Truth Frees)Founded1955Closed2016School boardLimestone District School BoardPrincipalAnn Marie McDonaldGrades9-12Colour(s)Red and Black Team nameRaidersYearbookCh…

La bureautique est l'ensemble des techniques et des moyens tendant à automatiser les activités de bureau et, principalement, le traitement et la communication de la parole, de l'écrit et de l'image. Histoire Le mot « Bureautique » a été proposé pour la première fois en 1976 à Grenoble par un groupe de chercheurs dont Louis Naugès était un des animateurs. Le problème était de traduire les mots anglais « office automation ». On avait hésité entre « burea…

1998 Edition of the Super Bowl 1998 Super Bowl redirects here. For the Super Bowl that was played at the completion of the 1998 season, see Super Bowl XXXIII. Super Bowl XXXII Green Bay Packers (2)(NFC)(13–3) Denver Broncos (4)(AFC)(12–4) 24 31 Head coach:Mike Holmgren Head coach:Mike Shanahan 1234 Total GB 7737 24 DEN 71077 31 DateJanuary 25, 1998 (1998-01-25)StadiumQualcomm Stadium, San Diego, CaliforniaMVPTerrell Davis, running backFavoritePackers by 11[1][2]RefereeEd…

Species of flowering plant Senecio pulcher Scientific classification Kingdom: Plantae Clade: Tracheophytes Clade: Angiosperms Clade: Eudicots Clade: Asterids Order: Asterales Family: Asteraceae Genus: Senecio Species: S. pulcher Binomial name Senecio pulcherHook. & Arn.[1] Range of Senecio pulcher. Senecio pulcher is an ornamental plant native to the wet valleys & slopes and flooded rocky[2] habitats in Argentina, Brazil, and Uruguay. Cited in Flora Brasiliensis[…

Pour les articles homonymes, voir Juninho (homonymie). Juninho Juninho en 2016. Biographie Nom Antônio Augusto Ribeiro Reis Júnior Nationalité Brésilien Français (depuis 2007)[1] Nat. sportive Brésilien Naissance 30 janvier 1975 (49 ans) Recife (Brésil) Taille 1,78 m (5′ 10″) Poste Milieu offensif Pied fort Droit Parcours junior Années Club 1991-1993 Sport Recife Parcours senior1 AnnéesClub 0M.0(B.) 1993-1995 Sport Recife 089 0(27)[2] 1995-2001 Vasco da Gama 265 0(54)…

2005 film FactotumTheatrical release posterDirected byBent HamerWritten byBent HamerJim StarkBased onFactotumby Charles BukowskiProduced byBent HamerJim StarkStarringMatt DillonLili TaylorMarisa TomeiCinematographyJohn Christian RosenlundEdited byPal GengenbachMusic byKristin AsbjørnsenProductioncompaniesBulbul FilmsCanal+Celluloid DreamsFactotumMBP (Germany)Mikado FilmNetwork Movie Film- und FernsehproduktionNorsk FilmfondNorsk FilmstudioNorwegian Film InstitutePandora FilmproduktionSF Norge A…

The Mysterious Numbers of the Hebrew Kings (1951)[1] adalah rekonstruksi kronologi kerajaan Israel dan Yehuda oleh Edwin R. Thiele. Buku itu awalnya merupakan disertasi doktornya dan secara luas dianggap sebagai karya definitif tentang kronologi raja-raja Ibrani.[2] Buku ini dianggap karya klasik dan komprehensif dalam perhitungan masa pemerintahan raja, kalender, dan pemerintahan bersama, berdasarkan Alkitab dan sumber di luar Alkitab. Kronologi Alkitab Masa hidup raja-raja Isra…

System on a chip (SoC) designed by Apple Inc. Apple A10 FusionGeneral informationLaunchedSeptember 7, 2016DiscontinuedMay 10, 2022Designed byApple Inc.Common manufacturer(s)TSMC[1]Product codeAPL1W24Max. CPU clock rateto 2.34 GHz[2]CacheL1 cachePer core: 64 KB instruction + 64 KB dataL2 cache3 MB sharedL3 cache4 MB sharedArchitecture and classificationApplicationMobileTechnology node16FFC nmMicroarchitectureHurricane and ZephyrInstruction setARM…

This article does not cite any sources. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed.Find sources: 2004 European Parliament election in Austria – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (December 2009) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) 2004 European Parliament election in Austria ← 1999 13 June 2004 2009 → 18 seats to the European Par…

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages) This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed.Find sources: Vishwakarma Institute of Technology – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (March 2015) (Learn how and …

Cet article est une ébauche concernant une commune de l’Eure. Vous pouvez partager vos connaissances en l’améliorant (comment ?). Le bandeau {{ébauche}} peut être enlevé et l’article évalué comme étant au stade « Bon début » quand il comporte assez de renseignements encyclopédiques concernant la commune. Si vous avez un doute, l’atelier de lecture du projet Communes de France est à votre disposition pour vous aider. Consultez également la page d’aide à la …

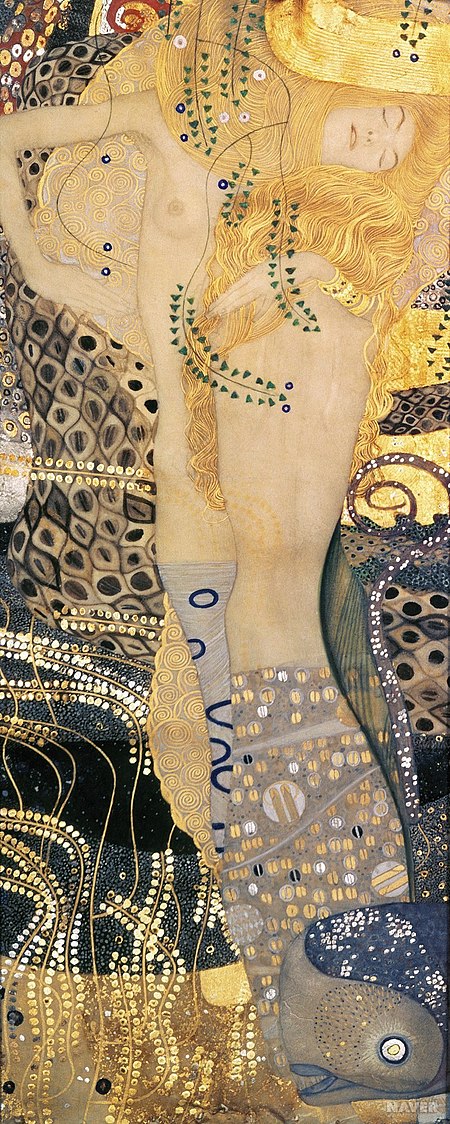

Painting by Gustav Klimt Water Serpents IIArtistGustav KlimtYear1904–1907MediumOil on canvasDimensions80 cm × 145 cm (31 in × 57 in)LocationPrivate collection, Asia Water Serpents II, also referred to as Wasserschlangen II, is an oil painting made by Gustav Klimt in 1907. It is the follow-up painting to the earlier painting Water Serpents I. Like the first painting, Water Serpents II deals with the sensuality of women's bodies and same-sex relationsh…

Untuk pengertian lain, lihat Bonto Bahari. Bonto BahariKecamatanNegara IndonesiaProvinsiSulawesi SelatanKabupatenBulukumbaPemerintahan • Camat-Populasi • Total25,233 jiwa jiwaKode Kemendagri73.02.03 Kode BPS7302030 Luas- km²Desa/kelurahan- Annyorong lopi atau tradisi gotong royong mendorong perahu di Bonto Bahari Bonto Bahari adalah sebuah kecamatan di Kabupaten Bulukumba, Sulawesi Selatan, Indonesia. Kecamatan Bonto Bahari berjarak sekitar 24 Km dari ibu kota Kabup…

密西西比州 哥伦布城市綽號:Possum Town哥伦布位于密西西比州的位置坐标:33°30′06″N 88°24′54″W / 33.501666666667°N 88.415°W / 33.501666666667; -88.415国家 美國州密西西比州县朗兹县始建于1821年政府 • 市长罗伯特·史密斯 (民主党)面积 • 总计22.3 平方英里(57.8 平方公里) • 陸地21.4 平方英里(55.5 平方公里) • �…