Law of the Soviet Union

|

Artikel ini perlu dikembangkan agar dapat memenuhi kriteria sebagai entri Wikipedia.Bantulah untuk mengembangkan artikel ini. Jika tidak dikembangkan, artikel ini akan dihapus. Artikel ini tidak memiliki referensi atau sumber tepercaya sehingga isinya tidak bisa dipastikan. Tolong bantu perbaiki artikel ini dengan menambahkan referensi yang layak. Tulisan tanpa sumber dapat dipertanyakan dan dihapus sewaktu-waktu.Cari sumber: Aji Nikutak – berita · surat kabar · buku…

The method of images (or method of mirror images) is a mathematical tool for solving differential equations, in which boundary conditions are satisfied by combining a solution not restricted by the boundary conditions with its possibly weighted mirror image. Generally, original singularities are inside the domain of interest but the function is made to satisfy boundary conditions by placing additional singularities outside the domain of interest. Typically the locations of these additional singu…

Sporting event delegationCzech Republic at the2013 World Aquatics ChampionshipsFlag of the Czech RepublicFINA codeCZENational federationČeský svaz plaveckých sportůWebsiteplavani.cstv.czin Barcelona, SpainCompetitors20 in 4 sportsMedals Gold 0 Silver 0 Bronze 0 Total 0 World Aquatics Championships appearances199419982001200320052007200920112013201520172019202220232024Other related appearances Czechoslovakia (1973–1991) Czech Republic competed at the 2013 World Aquatics Championships i…

Rapat Umum Chartis di Kennington Common, London, 1848. Chartisme adalah gerakan kaum pekerja yang menuntut reformasi politik di Britania Raya antara 1838 dan 1848. Namanya diambil dari People's Charter of 1838. Kata Chartisme adalah nama induk dari beberapa kelompok lokal yang saling terkoordinasi, biasanya disebut Working Men's Association, dan keanggotaannya memuncak tahun 1839, 1842, dan 1848. Gerakan ini bermula di kalangan pengrajin kecil, seperti pembuat sepatu, tukang cetak, penjahit, dan…

Sebuah insiden terjadi di perbatasan Albania – Yugoslavia pada bulan April 1999 ketika Tentara Yugoslavia menembaki beberapa kota perbatasan Albania di sekitar Krumë, Tropojë. Di desa-desa ini, para pengungsi ditampung setelah melarikan diri dari perang yang sedang berlangsung di Kosovo dengan menyeberang ke Albania.[1] Pada tanggal 13 April 1999, infanteri Yugoslavia memasuki wilayah Albania untuk menutup area yang digunakan oleh KLA untuk melancarkan serangan terhadap sasaran Yugos…

For other uses, see Awn (disambiguation). This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed.Find sources: Awn botany – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (December 2009) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) A wild rye ear (spike) with awns Awns on the fruit of an Australian species of grass In bot…

Yang MuliaJosef StanglUskup WürzburgPenunjukan27 Juni 1957Awal masa jabatan12 September 1957Masa jabatan berakhir8 Januari 1979PendahuluJulius August DöpfnerPenerusPaul-Werner ScheeleImamatTahbisan imam16 Maret 1930Tahbisan uskup12 September 1957oleh Josef SchneiderInformasi pribadiNama lahirJosef StanglLahir(1907-03-12)12 Maret 1907Kronach, Kekaisaran JermanWafat8 April 1979(1979-04-08) (umur 72)Schweinfurt, Jerman BaratKewarganegaraanJermanDenominasiGereja Katolik RomaSemboyandomin…

Jason Jordan AngleJordan di bulan Maret 2015Nama lahirNathan Everhart Angle[1]Lahir28 September 1988 (umur 35)[2]Tinley Park, Illinois, Amerika Serikat[2]Alma materIndiana UniversityKarier gulat profesionalNama ringJason Jordan[2]Tinggi6 ft 3 in (1,91 m)[3]Berat245 pon (111 kg)[3]Asal dariChicago, Illinois[3]Dilatih olehFlorida Championship WrestlingDebut30 September 2011 Nathan Everhart Angle (lahir 28 Septemb…

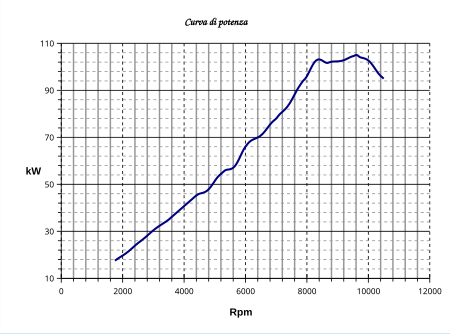

Questa voce o sezione sull'argomento fisica non cita le fonti necessarie o quelle presenti sono insufficienti. Puoi migliorare questa voce aggiungendo citazioni da fonti attendibili secondo le linee guida sull'uso delle fonti. Segui i suggerimenti del progetto di riferimento. La potenza, nella fisica, è definita operativamente come l'energia trasferita[1] nell'unità di tempo. Dire che un macchinario ha un'alta potenza (W) vuol dire che riesce a trasferire una grande quantità di e…

Pour les articles homonymes, voir Sosa. Sosa Cuervo est un nom espagnol. Le premier nom de famille, paternel, est Sosa ; le second, maternel, souvent omis, est Cuervo. Iván SosaInformationsNom de naissance Iván Ramiro Sosa CuervoNaissance 31 octobre 1997 (26 ans)PascaNationalité colombienneÉquipe actuelle MovistarSpécialité GrimpeurÉquipes amateurs 2016Maltinti Lampadari-Banca di CambianoÉquipes professionnelles 2017-2018Androni Giocattoli01.2019-04.2019Sky05.2019-2021Ineos2022…

الخطوط الجوية الفرنسية الرحلة 296 الطائرة المنكوبة نفسها في مطار باريس شارل ديغول في 26 يونيو 1988 (تقريبا قبل عدة ساعات من الحادثة) ملخص الحادث التاريخ 26 يونيو 1988 البلد فرنسا نوع الحادث خطأ عمال طباعة خرائط الخطوط الجوية الفرنسية والتصميم الفاشل والأعطال التقنية لطائرة إيرب…

Festival Film Indonesia ke-30Tanggal6 Desember 2010TempatBallroom Central Park, Jakarta BaratPembawa acara Atiqah Hasiholan Raffi Ahmad Vincent PenyelenggaraKomite Festival Film IndonesiaSorotanFilm Terbaik3 Hati Dua Dunia, Satu Cinta[1][2]Penyutradaraan TerbaikBenni Setiawan3 Hati Dua Dunia, Satu CintaAktor TerbaikReza Rahadian3 Hati Dua Dunia, Satu CintaAktris TerbaikLaura Basuki3 Hati Dua Dunia, Satu CintaPenghargaan seumur hidupTuti Indra MalaonPenghargaan terbanyak3 Hati Dua…

County in Illinois, United States County in IllinoisRichland CountyCountyRichland County Courthouse in OlneyLocation within the U.S. state of IllinoisIllinois's location within the U.S.Coordinates: 38°43′N 88°05′W / 38.71°N 88.09°W / 38.71; -88.09Country United StatesState IllinoisFoundedFebruary 24, 1841Named forRichland County, OhioSeatOlneyLargest cityOlneyArea • Total362 sq mi (940 km2) • Land356 sq mi…

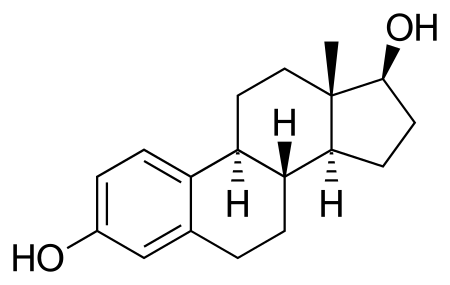

Estriol Estradiol Estron Estrogen (atau oestrogen) adalah sekelompok senyawa steroid yang berfungsi terutama sebagai hormon seks wanita. Walaupun terdapat baik dalam tubuh pria maupun wanita, kandungannya jauh lebih tinggi dalam tubuh wanita usia subur. Hormon ini menyebabkan perkembangan dan mempertahankan tanda-tanda kelamin sekunder pada wanita, seperti payudara, dan juga terlibat dalam penebalan endometrium maupun dalam pengaturan siklus haid. Pada saat menopause, estrogen mulai berkurang se…

Basko Grand Mall berdiri di samping Batang Kuranji Berikut ini adalah daftar pusat perbelanjaan di Padang, Sumatera Barat: Nama Lokasi Keterangan Basko Grand Mall Jalan Prof. Dr. Hamka No. 2 Pusat perbelanjaan modern ini mulai beroperasi pada tahun 1995 dengan nama Minang Plaza. Pada tahun 2009, mal ini diintegrasikan dengan Western Basko Hotel (sekarang Premier Basko Hotel, hotel berbintang lima pertama di Padang) dan berganti nama menjadi Basko Grand Mall. Christine Hakim Idea Park (CHIP) Jala…

Shabana AzmiAzmi di Apsara Film Awards pada 2015 Anggota Parlemen (Nominasi)Masa jabatan27 Agustus 1997 – 26 Agustus 2003 Informasi pribadiLahirShabana Kaifi Azmi18 September 1950 (umur 73)Hyderabad, Negara Bagian Hyderabad, India(sekarang Telangana, India)Suami/istriJaved Akhtar (m. 1984)Orang tuaKaifi AzmiShaukat KaifiPekerjaanPemeran, Penggiat sosialSunting kotak info • L • B Shabana Azmi (lahir 18 September 1950) adalah seorang pem…

Erwin Buana Utama Kepala Staf Komando Operasi Angkatan Udara III ke-2Masa jabatan24 Juni 2019 – 26 Agustus 2020 PendahuluI Wayan SulabaPenggantiHesly Paat Informasi pribadiLahir3 Mei 1964 (umur 59)Balikpapan, Kalimantan TimurAlma materAkademi Angkatan Udara (1987)Karier militerPihak IndonesiaDinas/cabang TNI Angkatan UdaraMasa dinas1987—2022Pangkat Marsekal Muda TNISatuanKorps PenerbangSunting kotak info • L • B Marsekal Muda TNI (Purn.) Erwin Buana …

Narragansett Chief (c. 1565 – 1647) For other uses, see Canonicus (disambiguation). CanonicusChief of the NarragansettSucceeded byMiantonomoh Personal detailsBornc. 1565DiedJune 4, 1647(1647-06-04) (aged 81–82)RelationsMiantonomoh (nephew) Canonicus' mark as seen on the 1638 deed of Providence to Roger Williams The original 1636 deed to Providence, signed by Chief Canonicus Canonicus (c. 1565 – June 4, 1647) was a chief of the Narragansett people. He was wary of the colonial settlers,…

Category in the Köppen climate classification system Humid continental climate worldwide, utilizing the Köppen climate classification Dsa Dsb Dwa Dwb Dfa Dfb A humid continental climate is a climatic region defined by Russo-German climatologist Wladimir Köppen in 1900,[1] typified by four distinct seasons and large seasonal temperature differences, with warm to hot (and often humid) summers, and cold (sometimes se…

Boeing B-17 Flying FortressB-17 Flying FortressTipeHeavy bomber Strategic bomberTerbang perdana28 Juli 1935Dipensiunkan1968 (Brazilian Air Force)Pengguna utamaUnited States Army Air ForcesPengguna lainRoyal Air ForceTahun produksi1936–1945Jumlah produksi12,731Harga satuanUS$238,329VarianXB-38 Flying Fortress YB-40 Flying Fortress C-108 Flying Fortress Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress adalah sebuah pesawat pengebom pengintai (reconnaissance aircraft) sayap rendah (low win…