|

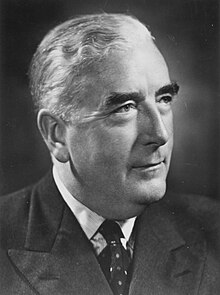

Robert Menzies

Sir Robert Gordon Menzies (20 December 1894 – 15 May 1978) was an Australian politician and lawyer who served as the 12th prime minister of Australia from 1939 to 1941 and from 1949 to 1966. He held office as the leader of the United Australia Party (UAP) in his first term, and subsequently as the inaugural leader of the Liberal Party of Australia in his second. He was the member of parliament (MP) for the Victorian division of Kooyong from 1934 to 1966. He is the longest-serving prime minister in Australian history. Menzies studied law at the University of Melbourne and became one of Melbourne's leading lawyers. He was Deputy Premier of Victoria from 1932 to 1934, and then transferred to Federal Parliament, subsequently becoming Attorney-General of Australia and Minister for Industry in the government of Joseph Lyons. In April 1939, following Lyons's death, Menzies was elected leader of the United Australia Party (UAP) and sworn in as prime minister. He authorised Australia's entry into World War II in September 1939, and spent four months in England to participate in meetings of Churchill's war cabinet. On his return to Australia in August 1941, Menzies found that he had lost the support of his party and consequently resigned as prime minister. He subsequently helped to create the new Liberal Party, and was elected its inaugural leader in August 1945. At the 1949 federal election, Menzies led the Liberal–Country coalition to victory and returned as prime minister. His appeal to the home and family, promoted via reassuring radio talks, matched the national zeitgeist as the economy grew and middle-class values prevailed; the Australian Labor Party's support had also been eroded by Cold War scares. After 1955, his government also received support from the Democratic Labor Party, a breakaway group from the Labor Party. Menzies won seven consecutive elections during his second period, eventually retiring as prime minister in January 1966. Despite the failures of his first administration, his government is remembered for its development of Australia's capital city of Canberra, its expanded post-war immigration scheme, emphasis on higher education, and national security policies, which saw Australia contribute troops to the Korean War, the Malayan Emergency, the Indonesia–Malaysia confrontation, and the Vietnam War. Early lifeBirth and family backgroundRobert Gordon Menzies was born on 20 December 1894 at his parents' home in Jeparit, Victoria.[1] He was the fourth of five children born to Kate (née Sampson) and James Menzies; he had two elder brothers, an elder sister Isabel, and a younger brother. Menzies was the first Australian prime minister to have two Australian-born parents: his father was born in Ballarat and his mother in Creswick. His grandparents on both sides had been drawn to Australia by the Victorian gold rush. His maternal grandparents were born in Penzance, Cornwall.[2] His paternal grandfather, also named Robert Menzies, was born in Renfrewshire, Scotland, and arrived in Melbourne in 1854.[3] The following year he married Elizabeth Band, the daughter of a cobbler from Fife.[4] Menzies was proud of his Scottish heritage, and preferred his surname to be pronounced in the traditional Scottish manner (/ˈmɪŋɪs/ MING-iss) rather than as it is spelled (/ˈmɛnziz/ MEN-zeez). This gave rise to his nickname "Ming", which was later expanded to "Ming the Merciless" after the comic strip character.[5] His middle name was given in honour of Charles George Gordon.[6] The Menzies family had moved to Jeparit, a small Wimmera township, in the year before Robert's birth.[2] At the 1891 census, the settlement had a population of just 55 people.[7] His elder siblings had been born in Ballarat, where his father was a locomotive painter at the Phoenix Foundry. Seeking a new start, he moved the family to Jeparit to take over the general store,[2] which "survived rather than prospered".[7] During Menzies's childhood, three of his close relatives were elected to parliament. His uncle Hugh was elected to the Victorian Legislative Assembly in 1902, followed by his father in 1911, while another uncle, Sydney Sampson, was elected to the federal Australian House of Representatives in 1906.[8] Each of the three represented rural constituencies, and were defeated after a few terms. Menzies's maternal grandfather John Sampson was active in the trade union movement. He was the inaugural president of the Creswick Miners' Association, which he co-founded with future Australian Labor Party MP William Spence, and was later prominent in the Amalgamated Miners' Association.[2] Childhood Growing up, Menzies and his siblings "had the normal enjoyments and camaraderies of a small country town".[9] He began his formal education in 1899 at the Jeparit State School, a single-teacher one-room school.[6] When he was about eleven, he and his sister were sent to Ballarat to live with his paternal grandmother; his two older brothers were already living there. In 1906, Menzies began attending the Humffray Street State School in Bakery Hill. The following year, aged 13, he ranked first in the state-wide scholarship examinations. This feat financed the entirety of his secondary education, which had to be undertaken at private schools, as Victoria did not yet have a system of public secondary schools.[10] In 1908 and 1909, Menzies attended Grenville College, a small private school in Ballarat Central.[11] He and his family moved to Melbourne in 1910, where he enrolled in Wesley College.[12] Menzies was "not very interested in and certainly incompetent at sport", but excelled academically. In his third and final year at Wesley he won a £40 exhibition for university study, one of 25 awarded by the state government.[13] UniversityIn 1913, Menzies entered the Melbourne Law School. He won a variety of prizes, exhibitions, and scholarships during his time as a student, graduating as a Bachelor of Laws (LL.B.) in 1916 and a Master of Laws (LL.M.) in 1918. He did, however, fail Latin in his first year.[14] One of his prize-winning essays, The Rule of Law During the War, was published as a brochure with an introduction by Harrison Moore, the law school dean. In 1916, Menzies was elected president of the Student Representatives' Council and editor of the Melbourne University Magazine. He wrote both prose and poetry for the magazine,[15] and also contributed a song about "little Billy Hughes" to an end-of-year revue.[16] Menzies was also president of the Students' Christian Union, a founding member of the Historical Society, and a prominent member of the Law Students' Society. He had "a reputation as an "unusually bright and articulate member of the undergraduate community", and was known as a skilful debater.[15] However, he had also begun to develop the traits of pomposity and arrogance that would cause difficulties later in his career. His fellow law student and future parliamentary colleague Percy Joske noted Menzies as a student "did not suffer fools gladly [...] the trouble was that his opponents frequently were not fools and that he tended to say things that were not only cutting and unkind but that were unjustified".[17] During World War I, Menzies served his compulsory militia service in the Melbourne University Rifles (a part-time militia unit)[18] from 1915 to 1919.[19] This unit was not efficient and Menzies noted in his diary that training in even basic skills such as rifle shooting was sub-standard.[19] He was commissioned a second lieutenant on 6 January 1915.[20] Unlike many of his contemporaries, he did not volunteer for overseas service, something that would later be used against him by political opponents; in 1939 he described it as "a stream of mud through which I have waded at every campaign in which I have participated". Menzies never publicly addressed the reasons for his decision not to enlist, stating only that they were "compelling" and related to his "intimate personal and family affairs".[21] His two older brothers did serve overseas. In a 1972 interview, his brother Frank Menzies recalled that a "family conference" had determined that Robert should not enlist. They believed that having two of the family's three adult sons serving overseas was a sufficiently patriotic contribution to the war effort, and that the family's interests would be served best by Robert continuing his academic career.[22] Another reason for keeping one of the elder sons home was the health of their father, James, who was physically unwell and emotionally unstable at the time.[23] It has been noted that, as a student, Menzies supported the introduction of compulsory overseas conscription, which if implemented would have made him one of the first to be conscripted.[19] Promoted to lieutenant, he resigned his commission with effect from 16 February 1921.[24] Legal careerAfter graduating from the University of Melbourne in 1916 with first-class honours in Law, Menzies was admitted to the Victorian Bar and to the High Court of Australia in 1918. Establishing his own practice in Melbourne, Menzies specialised chiefly in constitutional law which he had read with the leading Victorian jurist and future High Court judge, Sir Owen Dixon.[8] In 1920, Menzies was an advocate for the Amalgamated Society of Engineers which eventually took its appeal to the High Court of Australia.[8] The case became a landmark authority for the positive reinterpretation of Commonwealth powers over those of the States. The High Court's verdict raised Menzies's profile as a skilled advocate, and eventually he was appointed a King's Counsel in 1929.[25] Early career in politicsState politics In 1928, Menzies entered state parliament as a member of the Victorian Legislative Council from East Yarra Province, representing the Nationalist Party of Australia. He stood for constitutional democracy, the rule of law, the sanctity of contracts and the jealous preservation of existing institutions. Suspicious of the Labor Party, Menzies stressed the superiority of free enterprise except for certain public utilities such as the railways.[26] His candidacy was nearly defeated when a group of ex-servicemen attacked him in the press for not having enlisted, but he survived this crisis. Within weeks of his entry to parliament, he was made a minister without portfolio in a new minority Nationalist State government led by Premier William McPherson. The new government had formed when the previous Labor government lost the support of the cross-bench Country Progressives.[27] The following year he shifted to the Victorian Legislative Assembly as the member for the Electoral district of Nunawading. In 1929, he founded the Young Nationalists as his party's youth wing and was its first president. Holding the portfolios of Attorney-General and Minister for the Railways, Menzies was Deputy Premier of Victoria from May 1932 until July 1934. Federal politicsIn August 1934, Menzies resigned from state parliament to contest the federal Division of Kooyong in the upcoming general election for the United Australia Party (UAP), which was the result of a merger during his tenure as a state parliamentarian of the Nationalists, Labor dissidents and the Australian Party. The previous member, John Latham, had given up the seat in order to prepare for appointment as Chief Justice of Australia. Kooyong was a safely conservative seat based on Kew, and Menzies won easily. He was immediately appointed Attorney-General of Australia and Minister for Industry in the Lyons government. In 1937 he was appointed a Privy Counsellor. In late 1934 and early 1935 Menzies, then attorney-general, unsuccessfully prosecuted the government's highly controversial case for the attempted exclusion from Australia of Egon Kisch, a Czech Jewish communist.[28] The initial prohibition on Kisch's entry to Australia, however, had not been imposed by Menzies but by the Country Party minister for the interior, Thomas Paterson.[8] Menzies had extended discussions with British experts on Germany in 1935, but could not make up his mind whether Adolf Hitler was a "real German patriot" or a "mad swash-buckler".[29] He condemned Nazi antisemitism, in 1933 writing to the organisers of an anti-Nazi protest at the Melbourne Town Hall that "I hope that I may be associated with the protest of the meeting tonight against the barbaric and medieval persecution to which their fellow Jews in Europe are apparently being subjected".[30] In July 1939, Menzies, by then prime minister, declared in a speech that "history will label Hitler as one of the great men of the century".[31] In August 1938, while Attorney-General, Menzies spent several weeks on an official visit to Nazi Germany. He was strongly committed to democracy for the British peoples, but he initially thought that the Germans should take care of their own affairs.[citation needed] He strongly supported the appeasement policies of the Chamberlain government in London, and sincerely believed that war could and should be avoided at all costs.[32][33] after the visit to Germany in 1938, Menzies wrote that the "abandonment by the Germans of individual liberty ... has something rather magnificent about it".[34] Menzies also praised the "really spiritual quality in the willingness of Germans to devote themselves to the service and well-being of the state".[35] Menzies supported British foreign policy, including appeasement, and was initially reticent about the prospect of going to war with Germany. However, by September 1939 the unfolding crisis in Europe changed his public stance that the diplomatic efforts by Chamberlain and other leaders to broker a peace agreement had failed, and that war was now an inevitability. In his Declaration of War broadcast on 3 September 1939, Menzies explained the dramatic turn of events over the past twelve months necessitating this change of course:

Menzies went on to say that if Hitler's expansionist "policy were allowed to go unchecked there could be no security in Europe and there could be no just peace for the world".[37] However, in a letter written by Menzies on 11 September 1939, he privately urged for peace negotiations and the continuation of appeasement with Hitler.[38] Meanwhile, on the domestic front, animosity developed between Sir Earle Page and Menzies which was aggravated when Page became Acting Prime Minister during Lyons's illness after October 1938. Menzies and Page attacked each other publicly. He later became deputy leader of the UAP.[39] His supporters began promoting him as Lyons's natural successor; his critics accused Menzies of wanting to push Lyons out, a charge he denied. In 1938, as part of the Dalfram dispute, he was ridiculed as Pig Iron Bob, the result of an industrial conflict with the Waterside Workers' Federation of Australia whose members had refused to load Australian pig iron being sold to an arms manufacturer in the Empire of Japan, for that country's war against China.[40][41] In 1939, he resigned from the Cabinet in protest at postponement of the national insurance scheme and insufficient expenditure on defence. First prime ministership

With Lyons's sudden death on 7 April 1939, Page became caretaker prime minister until the UAP could elect a new leader. On 18 April 1939, Menzies was elected party leader over three other candidates. He was sworn in as prime minister eight days later. A crisis arose almost immediately, however, when Page refused to serve under him. In an extraordinary personal attack in the House, Page accused Menzies of cowardice for not having enlisted in the War, and of treachery to Lyons. Menzies then formed a minority government. When Page was deposed as Country Party leader a few months later, Menzies took the Country Party back into his government in a full-fledged Coalition, with Page's successor, Archie Cameron, as number-two-man in the government. Lead-up to World War IIDuring the Danzig crisis, Menzies, who had long felt that the Treaty of Versailles was too harsh towards Germany, supported having the Free City of Danzig (modern Gdańsk) rejoin Germany.[42] Though Hitler had only asked for extraterritorial highways across the Polish Corridor to link East Prussia with the rest of the Reich, Menzies also supported having the Polish Corridor returned to Germany.[42] Despite his support for the Germans' claims to Danzig, Menzies was opposed to the prospect of German domination of Europe. Menzies in a speech on 28 March 1939 declared: "I do not accept this doctrine of an unimpeded march by Germany to a territorial conquest of middle and southeastern Europe".[43] Ultimately, the fear of Japan proved decisive for Menzies, who believed that for Australia to not support Britain in the Danzig crisis would lead to Britain eventually abandoning Australia to face Japan alone.[42] The prospect of war in Europe threatened to undermine the Singapore strategy that called for the main British battle fleet to be sent out to Singapore (the major British naval base in Asia) in the event of a threat from Japan.[44] A war with Germany would require the majority of the Royal Navy's ships to stay within European waters, and an inability to execute the Singapore strategy as planned was widely feared in Canberra to be a strong encouragement for Japan to strike south against Australia.[44] However, Menzies had a strong faith in the ability of Neville Chamberlain to handle the Danzig crisis.[42] Menzies believed that the crisis should and would be resolved by a Munich-type deal under which the Free City of Danzig would be peacefully allowed to "go home to the Reich" while at the same time Germany should and would be deterred from going to war against Poland.[42] Though Menzies felt that Poland was in the wrong in opposing the return of the Free City to Germany, he did not want to see the crisis end with Poland being subjected to Germany.[45] Several times, Menzies declared that there were "two sides" both equally worthy of consideration to the Danzig dispute.[45] He dismissed the "jitters", as he called it, on the stock market in the summer of 1939 while he spoke of "an outpouring of the sentiments of peace in the minds of the people".[45] Throughout the summer of 1939, Menzies stressed in his speeches that war was "not inevitable" as he urged Australians to enjoy their summer vacations.[45] In the cabinet, Menzies was opposed to expanding the tiny Australian Army beyond its current size of 1, 571 soldiers on economic grounds.[45] The news of the Molotov–Ribbentrop pact of 22 August 1939 was greeted with both relief and concern in Menzies's cabinet. It was understood that the German-Soviet nonaggression pact ended the prospect of a "peace front" of Britain, France and the Soviet Union to deter Germany from invading Poland, and that war was more likely than not in Europe.[46] Conversely, the Molotov–Ribbentrop pact had (temporarily as it proved) alienated Japan from Germany, and within the Australian cabinet, it was felt that Japan would be less likely to enter a war against the British empire because of the German-Soviet agreement, which had come as a most unwanted surprise in Tokyo.[46] In Tokyo, the failure to achieve an alliance with Germany alongside the shock of the German-Soviet non-aggression pact caused the Japanese Prime Minister Baron Hiranuma Kiichirō to submit his resignation to the Emperor, which was accepted. The possibility that at least for the moment that Japan would stay neutral if the Danzig crisis led to war in Europe encouraged the cabinet in Canberra to stand by Britain.[46] At warOn 3 September 1939 Britain and France declared war on Germany due to its invasion of Poland on 1 September, leading to the start of World War II.[34] Menzies responded immediately by also declaring Australia to be at war in support of Britain, and delivered a radio broadcast to the nation on that same day, which began "Fellow Australians. It is my melancholy duty to inform you officially that in consequence of a persistence by Germany in her invasion of Poland, Great Britain has declared war upon her and that, as a result, Australia is also at war."[35][36] A couple of days after the declaration, Menzies recalled parliament and asked for general support as the government faced the enormous responsibility of leading the nation in war time. Page and Curtin, as party leaders, pledged their support for all that needed to be done for the defence of the country.[47] Thus, Menzies at the age of 44 found himself a wartime leader of a small nation of 7 million people. He was especially worried about the military threat from Japan. Australia had very small forces, and depended on Britain for defence against the looming threat of the Japanese Empire, with its 100 million people, a very powerful Army and Navy and an aggressive foreign policy. He hoped that a policy of appeasement would head off a war with Japan, and repeatedly pressured London.[48] Menzies did his best to rally the country, but the bitter memories of the disillusionment which followed World War I made his task difficult; this was compounded by his lack of a service record. Furthermore, as attorney-general and deputy prime minister, he had made an official visit to Germany in 1938, when the official policy of the Australian government, supported by the Opposition, was strong support for Neville Chamberlain's policy of Appeasement. Menzies, then also holding the responsibility for the Department of Munitions created a couple of months earlier, led the Coalition into the 1940 election and suffered an eight-seat swing, losing the slender majority he had inherited from Lyons. The result was a hung parliament, with the Coalition two seats short of a majority. Menzies managed to form a minority government with the support of two independent MPs, Arthur Coles and Alex Wilson. Labor, led by John Curtin, refused Menzies's offer to form a war coalition, and opposed using the Australian army for a European war, preferring to keep it at home to defend Australia. Labor agreed to participate in the Advisory War Council. Strategic debatesMenzies sent the bulk of the army to help the British in the Middle East and Singapore, and told Winston Churchill the Royal Navy needed to strengthen its Far Eastern forces.[49] On 11 August 1940, Churchill sent a long letter to Menzies promising that if Japan entered the war, Britain would activate the Singapore strategy by sending a strong Royal Navy force to Singapore.[50] Menzies continued to be worried about the fact that the Singapore base-despite being billed as the "Gibraltar of the East" was a base, not the fortress that it was presented as; about the shoddy state of the fortifications at Singapore; and about the lack of details in Churchill's promises.[50]  Just before the September 1940 election, on 13 August 1940, three members of Menzies's cabinet had been killed in an air crash—the Canberra air disaster—along with General Brudenell White, Chief of the General Staff; two other passengers and four crew.[51] This event weakened Menzies's government.[52] On the night of 11 November 1940, aircraft from the carriers of the Royal Navy's Mediterranean fleet disabled a number of Italian capital ships at anchor at the Italian base at Taranto. In December 1940, Menzies sent Churchill a letter expressing concern that the Imperial Japanese Navy might likewise use air power to cripple the Singapore base.[50] In the same letter, Menzies asked Churchill to activate the Singapore strategy by stationing at least three or four capital ships at Singapore.[50] In response, Churchill wrote back to Menzies that to say he would not have capital ships "sitting idle" at Singapore and that to transfer capital ships to Singapore would mean "ruining the Mediterranean situation. This I am sure you would not want to do unless or until the Japanese danger became far more menacing than at present".[50] In March 1941 and again in August 1941, Menzies appealed to Churchill in letters to activate the Singapore strategy as he wrote that he was highly concerned about Japanese ambitions in the Asia-Pacific region.[50] From 24 January 1941, Menzies spent four months in Britain discussing war strategy with Churchill and other Empire leaders, while his position at home deteriorated. En route to the UK he took the opportunity to stop over to visit Australian troops serving in the North African Campaign. On 20 February 1941, Churchill asked Menzies to give his approval to send the Australian forces in North Africa to Greece.[53] Like many other Australians of his generation, Menzies was haunted by the memory of the Battle of Gallipoli-which came about because of Churchill's plans to send an Allied fleet up the Dardanelles-and he was highly suspicious of another of Churchill's plans for victory in the Mediterranean.[53] On 25 February 1941, Menzies reluctantly gave his approval to send the 6th Division to Greece.[53] Professor David Day, an Australian historian, has posited that Menzies might have replaced Churchill as British prime minister, and that he had some support in the UK for this. Support came from Viscount Astor, Lord Beaverbrook and former WWI Prime Minister David Lloyd George,[54] who were trenchant critics of Churchill's purportedly autocratic style, and favoured replacing him with Menzies, who had some public support for staying on in the War Cabinet for the duration, which was strongly backed by Sir Maurice Hankey, former WWI Colonel and member of both the WWI and WWII War Cabinets. Writer Gerard Henderson has rejected this theory, but history professors Judith Brett and Joan Beaumont support Day, as does Menzies's daughter, Heather Henderson, who claimed Lady Astor "even offered all her sapphires if he would stay on in England".[54] Menzies came home to a hero's welcome. However, his support in Parliament was less certain. Not only did some Coalition MPs doubt his popularity in the electorate, but they also believed that a national unity government was the only long-term solution. Menzies's reputation was badly damaged by the failure of the Allied expedition to Greece, in which Australian troops played a prominent role.[55] The Australian Worker newspaper in an editorial on 11 June 1941 attacked Menzies for having "too readily acquiesced in the ill-starred Greek campaign, of which the Cretan misadventure was the inevitable sequel ... As a military adventure, it was madness. As a political gesture, it was stupid because it was doomed to failure."[55] Menzies sought to blame General Sir Thomas Blamey for the Greek expedition as he maintained that he had only given permission to send the Australians to Greece after Blamey did not oppose it.[55] Menzies maintained that if Blamey had given his disapproval in his opinion as a professional soldier, he would never have sent the Australians to Greece.[55] Matters came to a head in August, when the cabinet voted to have Menzies return to London to speak for Australia's interests in the War Cabinet. However, since Labor and the Coalition were level (both sides had 36 MPs), Menzies needed the support of the Labor Party in order to travel to Britain.[56] Amid rumours that Menzies's real intention was to launch a political career in Britain, Labor insisted that the crisis was too dire for Menzies to leave the country.[57] DownfallWith Labor unwilling to support him travelling to London and his position within his own party room weakening, Menzies called an emergency cabinet meeting. He announced his intention to resign and advise the Governor-General, Lord Gowrie to commission Curtin as prime minister. The Cabinet instead urged Menzies to make another overture to Labor for a national unity government, but Labor turned the offer down. With his position now untenable, Menzies resigned the prime ministership on 27 August 1941.[56] A joint UAP-Country Party conference chose Country Party leader Arthur Fadden as Coalition leader—and hence Prime Minister—even though the Country Party was the junior partner in the Coalition.[58] Menzies was bitter about this treatment from his colleagues, and nearly left politics,[59] but was persuaded to become Minister for Defence Co-ordination in Fadden's cabinet.[60] The Fadden government lasted only 40 days before being defeated on a confidence motion. On 9 October 1941, Menzies resigned as leader of the UAP after failing to convince his colleagues that he should become Leader of the Opposition in preference to Fadden. He was replaced as UAP leader by former prime minister Billy Hughes, who was 79 years old at the time.[61] InterregnumMenzies's Forgotten PeopleDuring his time in the political wilderness Menzies built up a large popular base of support by his frequent appeals, often by radio, to ordinary non-elite working citizens whom he called 'the Forgotten People'—especially those who were not suburban and rich or members of organised labour. From November 1941, he began a series of weekly radio broadcasts reaching audiences across New South Wales, Victoria and Queensland. A selection of these talks was edited into a book bearing the title of his most famous address, The Forgotten People, delivered on 22 May 1942. In this landmark address, Menzies appealed to his support base:

Menzies himself described The Forgotten People collection as 'a summarised political philosophy'. Representing the blueprint of his liberal philosophy, The Forgotten People encompassed a wide range of topics including Roosevelt's Four Freedoms, the control of the war, the role of women in war and peace, the future of capitalism, the nature of democracy and especially the role of the middle class, 'the forgotten people' of the title and their importance to Australia's future as a democracy.[63] The addresses frequently emphasised the values which Menzies regarded as critical to shaping Australia's wartime and postwar policies. These were essentially the principles of liberalism: individual freedom, personal and community responsibility, the rule of law, parliamentary government, economic prosperity and progress based on private enterprise and reward for effort.[63] After losing the UAP leadership, Menzies moved to the backbench. Besides his overall sense of duty, the war would have made it nearly impossible for him to return to his legal practice in any event.[56] Labor won a crushing victory at the 1943 election, taking 49 of 74 seats and 58.2 percent of the two-party-preferred vote as well as a Senate majority. The Coalition, which had sunk into near-paralysis in opposition, was knocked down to only 19 seats. Hughes resigned as UAP leader, and Menzies was elected as his successor on the second ballot, defeating three other candidates. The UAP also voted to end the joint opposition arrangement with the Country Party, allowing Menzies to replace Fadden as opposition leader. Formation of the Liberal PartySoon after his return, Menzies concluded that the UAP was at the end of its useful life. Menzies called a conference of anti-Labor parties with meetings in Canberra on 13 October 1944 and again in Albury (NSW) in December 1944. At the Canberra conference, the fourteen parties, with the UAP as the nucleus, decided to merge as one new non-Labor party—the Liberal Party of Australia. The organisational structure and constitutional framework of the new party was formulated at the Albury Conference. Officially launched at the Sydney Town Hall on 31 August 1945, the Menzies-led Liberal Party of Australia inherited the UAP's role as senior partner in the Coalition. Curtin died in office in 1945 and was succeeded by Ben Chifley. The reconfigured Coalition faced its first national test in the 1946 election. It won 26 of 74 seats on 45.9 percent of the two-party vote and remained in minority in the Senate. Despite winning a seven-seat swing, the Coalition failed to make a serious dent in Labor's large majority. 1949 election campaignOver the next few years, however, the anti-communist atmosphere of the early Cold War began to erode Labor's support. In 1947, Chifley announced that he intended to nationalise Australia's private banks, arousing intense middle-class opposition which Menzies successfully exploited. In addition to campaigning against Chifley's bank nationalization proposal, Menzies successfully led the 'No' case for a referendum by the Chifley government in 1948 to extend commonwealth wartime powers to control rents and prices.[8] In the election campaign of 1949, Menzies and his party were resolved to stamp out the communist movement and to fight in the interests of free enterprise against what they termed as Labor's 'socialistic measures'. If Menzies won office, he pledged to counter inflation, extend child endowment and end petrol rationing.[8] With the lower house enlarged from 74 to 121 seats, the Menzies Liberal/Country Coalition won the 1949 election with 74 House seats and 51.0 percent of the two-party vote but remained in minority in the Senate. Whatever else Menzies's victory represented, his anti-communism and advocacy for free enterprise had captured a new and formidable support base in postwar Australian society.[8] Second prime ministership After his election victory, Menzies returned to the office of prime minister on 19 December 1949. Cold War and national securityThe spectre of communism and the threat it was deemed to pose to national security became the dominant preoccupation of the new government in its first phase. Menzies introduced legislation in 1950 to ban the Communist Party, hoping that the Senate would reject it and give him a trigger for a double dissolution election, but Labor let the bill pass. It was subsequently ruled unconstitutional by the High Court. But when the Senate rejected his banking bill, he called a double dissolution election. At that election, the Coalition suffered a five-seat swing, winning 69 of 121 seats and 50.7 percent of the two-party vote. However, it won six seats in the Senate, giving it control of both chambers. Later in 1951 Menzies decided to hold a referendum on the question of changing the Constitution to permit the parliament to make laws in respect of Communists and Communism where he said this was necessary for the security of the Commonwealth. If passed, this would have given a government the power to introduce a bill proposing to ban the Communist Party. Chifley died a few months after the 1951 election. The new Labor leader, H. V. Evatt, campaigned against the referendum on civil liberties grounds, and it was narrowly defeated. Menzies sent Australian troops to the Korean War. Economic conditions deteriorated in the early 1950s and Labor was confident of winning the 1954 election. Menzies engaged in red-baiting of political opponents.[64]: 93 Shortly before the election, Menzies announced that a Soviet diplomat in Australia Vladimir Petrov, had defected, and that there was evidence of a Soviet spy ring in Australia, including members of Evatt's staff. Evatt felt compelled to state on the floor of Parliament that he'd personally written to Soviet Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov, who assured him there were no Soviet spy rings in Australia, bringing the House into silence momentarily before both sides of Parliament laughed at Evatt's naivety.[65] This Cold War scare was claimed by some to enable the Menzies government to win the election. The Menzies government won 64 of 121 seats and 49.3 percent of the two-party vote. Evatt accused Menzies of arranging Petrov's defection. The aftermath of the 1954 election caused a split in the Labor Party, with several anti-Communist members from Victoria defecting to form the Australian Labor Party (Anti-Communist). The new party directed its preferences to the Liberals, with the Menzies government re-elected with an increased majority at the 1955 election. Menzies was re-elected almost as easily at the 1958 election, again with the help of preferences from what had become the Democratic Labor Party. Foreign policy  The Menzies era saw immense regional changes, with post-war reconstruction and the withdrawal of European Powers and the British Empire from the Far East (including independence for India and Indonesia). In response to these geopolitical developments, the Menzies government maintained strong ties with Australia's traditional allies such as Britain and the United States while also reorienting Australia's foreign policy focus towards the Asia Pacific. With his first Minister for External Affairs, Percy Spender, the Menzies government signed the ANZUS treaty in San Francisco on 1 September 1951. Menzies later told parliament that this security pact between Australia, New Zealand and the United States was 'based on the utmost good will, the utmost good faith and unqualified friendship' saying 'each of us will stand by it'.[66] At the same time as strengthening the alliance with the United States, Menzies and Spender were committed to Australia being on 'good neighbour terms' with the countries of South and South East Asia. To help forge closer ties in the region, the Menzies government initiated the Colombo Plan that would see almost 40 000 students from the region come to study in Australia over the four subsequent decades.[67] Recognising the economic potential of a burgeoning postwar Japan, Menzies, together with Trade Minister Jack McEwan and his new minister for External Affairs, Richard Casey, negotiated the Commerce Agreement with Japan in 1957. This trade agreement was followed by bilateral agreements with Malaya in 1958 and Indonesia in 1959.[66]  Economic policy Throughout his second period in office, Menzies practised classical liberal economics with an emphasis on private enterprise and self-sufficiency in contrast to Labor's 'socialist objective'. Accordingly, the economic policy emphasis of the Menzies government moved towards tax incentives to release productive capacity, boosting export markets, research and undertaking public works to provide power, water and communications.[68] In 1951, the top marginal tax rate for incomes above £10,000 (equivalent to $487,272.73 in 2022[69]) was 75 per cent under Menzies; from 1955 until the mid-1980s, the top marginal tax rate was 67 per cent.[70] Social reform In 1949, Parliament legislated to ensure that all Aboriginal ex-servicemen should have the right to vote. In 1961 a Parliamentary Committee was established to investigate and report to the Parliament on Aboriginal voting rights, and in 1962, Menzies's Commonwealth Electoral Act provided that all Indigenous Australians should have the right to enrol and vote at federal elections.[71] In 1960, the Menzies government introduced a new pharmaceutical benefits scheme, which expanded the range of prescribed medicines subsidised by the government. Other social welfare measures of the government included the extension of the Commonwealth Child Endowment scheme, the pensioner medical and free medicines service, the Aged Persons' Homes Assistance scheme, free provision of life-saving drugs; the provision of supplementary pensions to dependent pensioners paying rent; increased rates of pension, unemployment and sickness benefits, and rehabilitation allowances; and a substantial system of tax incentives and rewards.[72] In 1961, the Matrimonial Causes Act introduced a uniform divorce law across Australia, provided funding for marriage counselling services and made allowances for a specified period of separation as sufficient grounds for a divorce.[73] In response to the decision by the Catholic Diocese of Goulburn in July 1962 to close its schools in protest at the lack of government assistance, the Menzies government announced a new package of state aid for independent and Catholic schools. Menzies promised five million pounds annually for the provision of buildings and equipment facilities for science teaching in secondary schools. Also promised were 10 000 scholarships to help students stay at school for the last two years with a further 2 500 scholarships for technical schools.[74] Despite the historically firm Catholic support base of the Labor Party, the Opposition under Arthur Calwell opposed state aid before eventually supporting it with the ascension of Gough Whitlam as Labor leader.  In 1965, the Menzies government took the decision to end open discrimination against married women in the public service, by allowing them to become permanent public servants, and allowing female officers who were already permanent public servants to retain that status after marriage.[75] Immigration policyThe Menzies government maintained and indeed expanded the Chifley Labor government's postwar immigration scheme established by Immigration Minister Arthur Calwell in 1947. Beginning in 1949, Immigration Minister Harold Holt decided to allow 800 non-European war refugees to remain in Australia, and Japanese war brides to be admitted to Australia.[76] In 1950, External Affairs Minister Percy Spender instigated the Colombo Plan, under which students from Asian countries were admitted to study at Australian universities, then in 1957, non-Europeans with 15 years' residence in Australia were allowed to become citizens. In a watershed legal reform, a 1958 revision of the Migration Act introduced a simpler system for entry and abolished the "dictation test" which had permitted the exclusion of migrants on the basis of their ability to take down a dictation offered in any European language. Immigration Minister Alick Downer announced that "distinguished and highly qualified Asians" might immigrate. Restrictions continued to be relaxed through the 1960s in the lead-up to the Holt government's watershed Migration Act, 1966.[77] This was despite a discussion with radio 2UE's Stewart Lamb in 1955, in which Menzies was a defender of the White Australia policy:

Higher education expansionThe Menzies government extended Federal involvement in higher education and introduced the Commonwealth scholarship scheme in 1951, to cover fees and pay a generous means-tested allowance for promising students from lower socioeconomic groups.[80] In 1956, a committee headed by Sir Keith Murray was established to inquire into the financial plight of Australia's universities, and Menzies's pumped funds into the sector under conditions which preserved the autonomy of universities.[8] In its support for higher education, the Menzies government tripled Federal government funding and provided emergency grants, significant increases in academic salaries, extra funding for buildings, and the establishment of a permanent committee, from 1961, to oversee and make recommendations concerning higher education.[81] Development of CanberraThe Menzies government developed the city of Canberra as the national capital. In 1957, the Menzies government established the National Capital Development Commission as independent statutory authority charged with overseeing the planning and development of Canberra.[82] During Menzies' time in office, the great bulk of the federal public service moved from the state capitals to Canberra.[82] Later lifeMenzies turned 71 in December 1965 and began telling others of his intention to retire in the new year. He informed cabinet of his decision on 19 January 1966 and resigned as leader of the Liberal Party the following day; Harold Holt was elected unopposed as his successor. Holt's swearing-in was delayed by the death of Defence Minister Shane Paltridge on 21 January. Menzies and Holt were pallbearers at Paltridge's state funeral in Perth on 25 January, before returning to Canberra where Menzies formally concluded his term on 26 January.[83] Menzies's farewell press conference was the first political press conference telecast live in Australia.[84] He resigned from Parliament on 17 February, ending 32 years in Parliament (most of them spent as either a cabinet minister or opposition frontbencher), a combined 25 years as leader of the non-Labor Coalition, and 38 years as an elected official. To date, Menzies is the last Australian prime minister to leave office on his or her own terms. He was succeeded as Liberal Party leader and prime minister by his former treasurer, Harold Holt. He left office at the age of 71 years, 1 month and 6 days, making him the oldest person ever to be prime minister. Although the coalition remained in power for almost another seven years (until the 1972 Federal election), it did so under four different prime ministers, in part due to his successor's death, only 22 months after taking office. On his retirement he became the thirteenth chancellor of the University of Melbourne and remained the head of the university from March 1967 until March 1972. Much earlier, in 1942, he had received the first honorary degree of Doctor of Laws of Melbourne University. His responsibility for the revival and growth of university life in Australia was widely acknowledged by the award of honorary degrees in the Universities of Queensland, Adelaide, Tasmania, New South Wales, and the Australian National University and by thirteen universities in Canada, the United States and Britain, including Oxford and Cambridge. Many learned institutions, including the Royal College of Surgeons (Hon. FRCS) and the Royal Australasian College of Physicians (Hon. FRACP), elected him to Honorary Fellowships, and the Australian Academy of Science, for which he supported its establishment in 1954, made him a fellow (FAAS) in 1958.[85] On 7 October 1965, Menzies was installed as the ceremonial office of Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports and Constable of Dover Castle as appointed by the Queen, which included an official residence at Walmer Castle during his annual visits to Britain. At the end of 1966 Menzies took up a scholar-in-residence position at the University of Virginia. He presented a series of lectures, published the following year as Central Power in the Australian Commonwealth. He later published two volumes of memoirs. In March 1967 he was elected Chancellor of Melbourne University, serving a five-year term.[86][87] In 1971, Menzies suffered a severe stroke and was permanently paralysed on one side of his body for the remainder of his life. He suffered a second stroke in 1972. His official biographer, Lady McNicoll wrote after his death in The Australian that Menzies was "splendid and sharp right up until the end" also that "each morning he underwent physiotherapy and being helped to face the day." In March 1977, Menzies accepted his knighthood of the Order of Australia (AK) from Queen Elizabeth in a wheelchair in the Long Room of the Melbourne Cricket Ground during the Centenary Test.[88] Personal lifeOn 27 September 1920, Menzies married Pattie Leckie at Kew Presbyterian Church in Melbourne. Pattie Leckie was the eldest daughter of John Leckie, a Deakinite Commonwealth Liberal who was elected the member for the Electoral district of Benambra in the Victorian Legislative Assembly in 1913. Soon after their marriage, the Menzies bought the house in Howard Street, Kew, which would become their family home for 25 years. They had three surviving children: Kenneth (1922–1993), Robert Jr (known by his middle name, Ian; 1923–1974)[89] and a daughter, Margery (known by her middle name, Heather; born 1928).[90] Another child died at birth. Kenneth was born in Hawthorn on 14 January 1922. He married Marjorie Cook on 16 September 1949,[91] and had six children: Alec, Lindsay, Robert III, Diana, Donald, and Geoffrey. He died in Kooyong on 8 September 1993.[92] Ian and Heather were both born in Kew, on 12 October 1923 and 3 August 1928, respectively. Ian was afflicted with an undisclosed illness for most of his life. He never married, nor had children, and died in 1974 in East Melbourne at the age of 50.[89] Heather married Peter Henderson, a diplomat and public servant (working at the Australian Embassy in Jakarta, Indonesia at the time of their marriage, and serving as the Secretary of the Department of Foreign Affairs from 1979 to 1984), on 1 May 1955. A daughter, Roberta, named after Menzies, was born in 1956. According to Mungo MacCallum, Menzies as prime minister engaged in an affair with Betty Fairfax, the first wife of Sir Warwick Oswald Fairfax.[93] That claim was subsequently disputed by Gerard Henderson and Menzies's own family.[94][95] Death and funeral Menzies died from a heart attack[96] while reading in his study at his Haverbrack Avenue home in Malvern, Melbourne on 15 May 1978. Tributes from across the world were sent to the Menzies family. Notably among those were from HM Queen Elizabeth II, Queen of Australia: "I was distressed to hear of the death of Sir Robert Menzies. He was a distinguished Australian whose contribution to his country and the Commonwealth will long be remembered", and from Malcolm Fraser, Prime Minister of Australia: "All Australians will mourn his passing. Sir Robert leaves an enduring mark on Australian history."[97] Menzies was accorded a state funeral, held in Scots' Church, Melbourne on 19 May, at which Prince Charles represented the Queen.[98] Other dignitaries to attend included current and former Prime Ministers of Australia Malcolm Fraser, John McEwen, John Gorton and William McMahon (the two surviving Labor Prime Ministers, Frank Forde and Gough Whitlam, did not attend the funeral), as well as the Governor General of Australia, Sir Zelman Cowan. Former Prime Ministers of the United Kingdom Alec Douglas-Home and Harold Wilson also attended. The service was and is to this day one of the largest state funerals ever held in Australia, with over 100,000 people lining the streets of Melbourne[99] from Scots' Church to Springvale Crematorium, where a private service was held for the Menzies family and a 19-gun salute was fired at the end of the ceremony. In July 1978, a memorial service was held for Menzies in the United Kingdom at Westminster Abbey.[100] Sir Robert and Dame Pattie Menzies's ashes are interred in the 'Prime Ministers Garden' within the grounds of Melbourne General Cemetery. Some of Menzies's detractors also commemorated his passing in 1978, with a screenprinted poster, Pig Iron Bob / Dead at last, designed by Chips Mackinolty from the Earthworks Poster Collective.[101] Religious viewsMenzies was the son of a Presbyterian-turned-Methodist lay preacher and imbibed his father's Protestant faith and values. During his studies at the University of Melbourne, Menzies was president of the Students' Christian Union.[102] Proud of his Scottish Presbyterian heritage with a living faith steeped in the Bible, Menzies nonetheless preached religious freedom and non-sectarianism as the norm for Australia. Indeed, his cooperation with Australian Catholics on the contentious state aid issue was recognised when he was invited as guest of honour to the annual Cardinal's Dinner in Sydney in 1964, presided over by Cardinal Norman Gilroy.[103] Legacy and assessmentMenzies was by far the longest serving Prime Minister of Australia, in office for a combined total of 18 years, five months and 12 days. His second period of 16 years, one month and seven days is by far the longest unbroken tenure in that office. During his second period he dominated Australian politics as no one else has ever done. He managed to live down the failures of his first period in office and to rebuild the conservative side of politics from the nadir it hit at the 1943 election. However, it can also be noted that while retaining government on each occasion, Menzies lost the two-party-preferred vote at three separate elections – in 1940, 1954 and 1961.[104][105] He was the only Australian prime minister to recommend the appointment of four governors-general (Viscount Slim, and Lords Dunrossil, De L'Isle, and Casey). Only two other prime ministers have ever chosen more than one governor-general.[106] The Menzies era saw Australia become an increasingly affluent society, with average weekly earnings in 1965 50% higher in real terms than in 1945. The increased prosperity enjoyed by most Australians during this period was accompanied by a general increase in leisure time, with the five-day workweek becoming the norm by the mid-1960s, together with three weeks of paid annual leave.[107] Several books have been filled with anecdotes about Menzies. While he was speaking in Williamstown, Victoria, in 1954, a heckler shouted, "I wouldn't vote for you if you were the Archangel Gabriel" – to which Menzies coolly replied, "If I were the Archangel Gabriel, I'm afraid you wouldn't be in my constituency."[108] Jo Gullett, who first knew him as a family friend of his father, Henry Gullett, wartime Minister for External Affairs, and who later served under Menzies as a Liberal Party member of parliament himself in Canberra in the 1950s, offered this assessment:

Planning for an official biography of Menzies began soon after his death, but it was long delayed by Dame Pattie Menzies's protection of her husband's reputation and her refusal to co-operate with the appointed biographer. [why?] In 1991, the Menzies family appointed A. W. Martin to write a biography, which appeared in two volumes, in 1993 and 1999. In 2019, Troy Bramston, a journalist for The Australian and a political historian, wrote the first biography of Menzies since Martin's two volumes, titled Robert Menzies: The Art of Politics. Bramston had access to previously unavailable Menzies family papers, conducted new interviews with Menzies' contemporaries and it was endorsed by Menzies' daughter, Heather Henderson. It was described as having "the most attractive combination of research and readability" of all the Menzies biographies.[110] The National Museum of Australia in Canberra holds a significant collection of memorabilia relating to Robert Menzies, including a range of medals and civil awards received by Sir Robert such as his Jubilee and Coronation medals, Order of Australia, Order of the Companions of Honour and US Legion of Merit. There are also a number of special presentation items including a walking stick, cigar boxes, silver gravy boats from the Kooyong electorate and a silver inkstand presented by Queen Elizabeth II.[111] Robert Menzies's personal library of almost 4,000 books is held at the University of Melbourne Library.[112] Published works

Titles and honours

Orders and Decorations

Freedom of the CityArms

Actors who have played Menzies

Eponyms of Menzies

Notes and references

Further reading

External linksWikimedia Commons has media related to Robert Menzies. Wikiquote has quotations related to Robert Menzies.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||