Trimpin

|

Read other articles:

Gerhana bulan Total27 Juli 2018 Ekliptika utaraBulan akan melewati pusat bayangan Bumi. Siklus Saros 129 (38 71) Gamma +0.1168 Durasi (jam:menit:detik) Totalitas 1:42:57 Parsial 3:54:32 Penumbra 6:13:48 Kontak (WIB) P1 00:14:49 U1 01:24:27 U2 02:30:15 Puncak 03:21:44 U3 04:13:12 U4 05:19:00 P4 06:28:37 Sebuah gerhana bulan total terjadi pada 27 Juli 2018 (28 Juli di Indonesia). Bulan akan melewati pusat dari bayangan Bumi. Gerhana ini akan menjadi gerhana bulan sentral yang pertama sejak 15 Juni…

Find the AnswerSingel oleh Arashidari album 5x20 All the Best!! 1999-2019Dirilis21 Februari 2018 (2018-02-21)FormatCD singleDirekam2017LabelJ StormJACA-5717-5718 (First-run limited edition (CD+DVD))[1]JACA-5719 (Regular edition (CD))[1]Kronologi singel Arashi Doors ~Yuuki no Kiseki~ (2017) Find the Answer (2018) Natsu Hayate (2018) Find the Answer adalah single ke-54 boyband Jepang Arashi. Single ini dirilis pada tanggal 21 Februari 2018 di bawah label rekaman J Storm. Find …

Halaman ini berisi artikel tentang warna. Untuk tumbuhan, lihat Kuma-kuma. Kuning Cempaka Bubuk kuma-kuma Koordinat warnaTriplet hex#F4C430sRGBB (r, g, b)(244, 196, 48)CMYKH (c, m, y, k)(4, 23, 81, 5)HSV (h, s, v)(45°, 80%, 96%)SumberMaerz dan Paul[1]B: Dinormalkan ke [0–255] (bita)H: Dinormalkan ke [0–100] (ratusan) Kuning cempaka atau Kurkuma (Inggris: Saffron yellowcode: en is deprecated ) adalah warna yang menyerupa…

Alat bantu dengar. Alat bantu dengar. Alat bantu dengar merupakan suatu alat akustik listrik yang dapat digunakan oleh manusia dengan gangguan fungsi pendengaran pada telinga. Biasanya alat ini dapat dipasang pada bagian dalam telinga manusia ataupun pada bagian sekitar telinga. Alat bantu dengar tersebut dibuat untuk memperkuat rangsangan bagian sel-sel sensorik telinga bagian dalam yang rusak terhadap rangsangan suara dan bunyi-bunyian dari luar. Alat bantu dengar tersebut juga merupakan sebua…

Radio station in Amarillo, Texas KXSS-FMAmarillo, TexasBroadcast areaAmarillo, TexasFrequency96.9 MHzBranding96.9 KISS FMProgrammingFormatTop 40 (CHR)AffiliationsCompass Media NetworksPremiere NetworksOwnershipOwnerTownsquare Media(Townsquare License, LLC)Sister stationsKATP, KIXZ, KMXJ-FM, KPRFHistoryFirst air date1972 (as KMML)Former call signsKMML-FM (1972–2008)[1]Call sign meaningK(X)iSSTechnical informationFacility ID9306ClassC1ERP100,000 wattsHAAT187 metersTransmitter coordinates…

Juan Fernando Quintero Informasi pribadiNama lengkap Juan Fernando Quintero PaniaguaTanggal lahir 18 Januari 1993 (umur 31)Tempat lahir Medellín, KolombiaTinggi 1,70 m (5 ft 7 in)Posisi bermain GelandangInformasi klubKlub saat ini FC PortoNomor 10Karier senior*Tahun Tim Tampil (Gol)2009–2011 Envigado 43 (5)2011–2012 Atlético Nacional 15 (4)2012–2013 Pescara 17 (1)2013- Porto 35 (6)Tim nasional‡2012- Kolombia 11 (1) * Penampilan dan gol di klub senior hanya dihitung …

Синелобый амазон Научная классификация Домен:ЭукариотыЦарство:ЖивотныеПодцарство:ЭуметазоиБез ранга:Двусторонне-симметричныеБез ранга:ВторичноротыеТип:ХордовыеПодтип:ПозвоночныеИнфратип:ЧелюстноротыеНадкласс:ЧетвероногиеКлада:АмниотыКлада:ЗавропсидыКласс:Птиц�…

Public school in Wilbraham, , Massachusetts, United StatesMinnechaug Regional High SchoolAddress621 Main StreetWilbraham, (Hampden County), Massachusetts 01095United StatesCoordinates42°06′41″N 72°26′31″W / 42.111287°N 72.441993°W / 42.111287; -72.441993InformationTypePublicCoeducationalOpen enrollment[1]Established1959School districtHampden-Wilbraham Regional School DistrictSuperintendentJohn ProvostPrincipalStephen HaleTeaching staff73.41 (FTE)[2…

العمايم الإحداثيات 36°19′51″N 9°50′43″E / 36.330899721182°N 9.8453464114593°E / 36.330899721182; 9.8453464114593 تقسيم إداري البلد تونس التقسيم الأعلى ولاية زغوان معلومات أخرى 1140 تعديل مصدري - تعديل لمعانٍ أخرى، طالع العمايم (توضيح). يفتقر محتوى هذه المقالة إلى الاستشه�…

Former train station in Folsom, California This article is about former Southern Pacific station. For the active RT light rail station, see Historic Folsom station. FolsomThe station building in 2008General informationLocation200 Wool St.Folsom, CaliforniaOwned bySacramento Valley Railroad (1856–1877)Sacramento and Placerville Railroad (1877–1888)Northern Railway (1888–1898)Southern Pacific Railroad (1898–1970)City of Folsom (1970– )HistoryOpenedFebruary 22, 1856Rebuiltc. 1906Ser…

English philosopher and novelist (1756–1836) For other people named William Godwin, see William Godwin (disambiguation). William GodwinPortrait by Henry William PickersgillBorn(1756-03-03)3 March 1756Wisbech, Cambridgeshire, EnglandDied7 April 1836(1836-04-07) (aged 80)Westminster, Middlesex, EnglandEducationHoxton AcademyNotable work Enquiry Concerning Political Justice Things as They Are Spouses Mary Wollstonecraft (m. 1797; died 1797)…

Державний комітет телебачення і радіомовлення України (Держкомтелерадіо) Приміщення комітетуЗагальна інформаціяКраїна УкраїнаДата створення 2003Керівне відомство Кабінет Міністрів УкраїниРічний бюджет 1 964 898 500 ₴[1]Голова Олег НаливайкоПідвідомчі орг�…

孔塔任 孔塔任是巴西的城市,位於該國東南部,距離首府貝洛奧里藏特21公里,由米納斯吉拉斯州負責管轄,始建於1716年,面積194平方公里,海拔高度858米,受熱帶氣候影響,2008年人口617,749。 外部連結 Ceasa Greater BH City government official site (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆) 这是一篇與巴西相關的地理小作品。你可以通过编辑或修订扩充其内容。查论编 查论编 米納斯吉拉�…

هذه مقالة غير مراجعة. ينبغي أن يزال هذا القالب بعد أن يراجعها محرر؛ إذا لزم الأمر فيجب أن توسم المقالة بقوالب الصيانة المناسبة. يمكن أيضاً تقديم طلب لمراجعة المقالة في الصفحة المخصصة لذلك. (ديسمبر 2020)Learn how and when to remove this message يفتقر محتوى هذه المقالة إلى الاستشهاد بمصادر. فضلاً، …

جون ستاينبيك (بالإنجليزية: Jeffery Ernest Steinbeck) معلومات شخصية اسم الولادة (بالإنجليزية: Jeffery Ernest Steinbeck) الميلاد 27 فبراير 1902(1902-02-27)ساليناس، كاليفورنيا الوفاة 20 ديسمبر 1968 (66 سنة)هارلم سبب الوفاة قصور القلب، ومرض قلبي وعائي مكان الدفن ساليناس، وكاليفورنيا مواطنة…

Шрифт «Ротунда» Gebrochene Schriften Роту́нда (итал. rotonda — круглая) — итальянский вариант готического письма (полуготический шрифт), появившийся в XII веке. Отличается округлённостью и отсутствием надломов. См. также Шрифт Готическое письмо Примечания Ссылки http://fonts.ru/help/term/t…

Indian film and television actress Not to be confused with Ambika Mohan or Ambika Sukumaran. AmbikaAmbika in 2014BornKallara, Thiruvananthapuram , Kerala, IndiaYears active1976–1989 (as a leading actress) 1997–present (as a supporting artist)Spouses Premkumar (m. 1988; div. 1996) Ravikanth (m. 2000; div. 2002) ChildrenRamkesav (b.1989)Rishikesh (b.1991)Parent(s)Kallara Kunjan Nair (fa…

جزء من سلسلة مقالات حولعلم تقسيم الأرض أساسيات علم شكل الأرض ومساحتها جيوديناميكيا جيوماتكس علم الخرائط التاريخ المفاهيم المسافة الجغرافية مجسم أرضي شكل الأرض (نصف قطر الأرض، ومحيطها) مسند جيوديسي جيوديسي نظام إحداثيات جغرافي عرض جغرافي / طول جغرافي إسقاط الخرائط سطح نا…

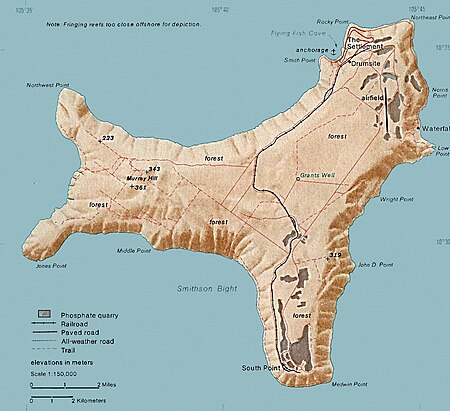

External territory of Australia This article is about the Australian territory in the Indian Ocean. For the island of Kiribati, see Kiritimati. For other uses, see Christmas Island (disambiguation). 10°29′24″S 105°37′39″E / 10.49000°S 105.62750°E / -10.49000; 105.62750 Place in AustraliaChristmas IslandAustralian Indian Ocean TerritoryExternal territory of AustraliaTerritory of Christmas Island圣诞岛领地 / 聖誕島領地 (Chinese)Wilayah Pulau Krism…

Female superior of a community of nuns, often an abbey For the Buddhist title, see Abbot and abbess (Buddhism). Reverend Mother redirects here. For the fictional characters of Dune, see Bene Gesserit. Eufemia Szaniawska, Abbess of the Benedictine Monastery in Nieśwież with a crosier, c. 1768, National Museum in Warsaw Abbess Joanna van Doorselaer de ten Ryen, Waasmunster Roosenberg Abbey Part of a series on theHierarchy of theCatholic ChurchSaint Peter Ecclesiastical titles (order of pre…