|

Truganini (book)

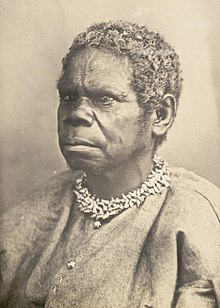

Truganini: Journey Through the Apocalypse is a 2020 biography of Truganini by Cassandra Pybus. Truganini, a Nuenonne woman who lived between 1812–1876, has been widely and falsely mythologised as "the last full-blooded Aboriginal Tasmanian", having survived the extermination of most of Tasmania's Indigenous population in the early 19th century. Truganini survived by acting as a guide for expeditions organised by colonists to capture and exile her fellow Aboriginal Tasmanians, and was later exiled herself to Wybalenna Aboriginal Establishment and Oyster Cove. Pybus has said that the goal of her writing was to "liberate the stories" of Aboriginal people trapped in colonists' accounts, and that the myth-making surrounding Truganini as the "last of her people" had overshadowed her agency and experiences.[1] The book was published by Allen & Unwin in 2020.[2] It was praised for its empathy and storytelling, but reviewers expressed frustration that Pybus was limited by the lack of a meaningful historical record told from Truganini's perspective. Pybus was forced to rely largely on eyewitness accounts written by colonists, particularly the diaries of George Augustus Robinson. The book was the winner of the 2021 National Biography Award[3] and was shortlisted for a Prime Minister's Literary Award[4] and a Queensland Literary Award.[5] SummaryThe book is divided into four sections: Friendly Mission (1829-1831), Extirpation and Exile (1831-1838), In Kulin Country (1839-1841), and The Way the World Ends (1842-1876). Truganini's story is primarily told through the diaries of George Augustus Robinson. Robinson met Truganini in April 1829, when she was aged about 17, and took her from a group of convict woodcutters back to her father on Bruny Island. Truganini helped Robinson to attract other Nuenonne to a newly established Aboriginal station at Missionary Bay. Truganini was particularly known for being a strong swimmer and helped gather food by diving for abalone and shellfish. Disease and violence quickly killed most of the Aboriginal residents of Missionary Bay, including Truganini's father Manganerer. At the end of 1829. Truganini and her new husband, a Nuenonne man named Wooredy, set off with Robinson as guides on a "friendly mission" to uncolonised parts of western Tasmania. During the mission they heard numerous stories of massacres of Aboriginal Tasmanians as part of the Black War, with the entire colony being placed under martial law in 1830. Pybus speculates that Truganini likely had little understanding of the purpose of Robinson's mission, but understood that staying with him provided safety and allowed her to continue her nomadic lifestyle. The second part of the book, Extirpation and Exile, narrates Truganini's role as a guide in a series of expeditions between 1831 and 1838 to capture the remaining Aboriginal clans in Tasmania. Most of Tasmania's Aboriginal population was exiled to islands in the Bass Strait, particularly to Wybalenna Aboriginal Establishment on Flinders Island, during this period. Truganini acted as a guide for a number of expeditions to capture and exile the remaining Aboriginal residents of Tasmania. On 3 February 1835, following the last of these expeditions, Robinson claimed that he had successfully cleared the entirety of Tasmania's original population. Robinson brought Truganini back to Hobart for several months, where she became a celebrity and was the subject of a number of paintings and sculptures. But in September 1835, Truganini and Wooredy were also exiled to the Wybalenna Aboriginal Establishment, where Robinson had been appointed superintendent. Truganini's name was changed to Lalla Rookh and she was subjected to attempts to assimilate her into European and Christian traditions, but she was resistant to these attempts. In March 1836 she left as a guide for a final expedition, and in July 1837 she was returned to Wyballena.  The third part of the book, In Kulin Country, describes Truganini's time in present day Victoria. Robinson was appointed Protector of Aborigines in Port Phillip District in 1839 and brought Truganini with him as a servant. Truganini ran away several times, and eventually ran away for good with a Tasmanian Aboriginal man named Maulboyheenner in 1841. They and their companions — Peevay and two women named Plorenernoopner and Maytepueminer — became outlaws after Peevay and Maulboyheenner beat two whalers to death. The five Tasmanians were taken back to Melbourne and tried. The three women were found not guilty of being accessories to the murder, but the two men were convicted and executed in 1842. Pybus writes that, according to the diary of Reverend Joseph Orton, Truganini expressed profound grief and bitterness at their execution. The final part of the book, The Way the World Ends, documents the last 34 years of Truganini's life after her time with Robinson. After her trial she was transported back to Wybalenna. Her husband Wooredy died on the journey. She often ran away and continued to take opportunities to engage in hunting and other cultural practices despite the disapproval of colonists. She was moved to Oyster Cove with the small number of remaining survivors in 1847. By 1872, she was the only remaining survivor at Oyster Cove and was frequently photographed and written about as "the last Tasmanian". She was eventually moved to Hobart in 1873 and died in May 1876. Reception Reviewers praised Pybus' attempts to "recover" Truganini, whose story had only been preserved in the historical record through the eyes of colonists and through posthumous myth-making. Pybus relies largely on the diaries of the colonist George Augustus Robinson in attempting to tell Truganini's story from an eyewitness' perspective.[7] Reviewers were divided in their assessment of how successful Pybus had been in recovering Truganini's perspective. Tom Lawson wrote in Australian Historical Studies that Truganini remains "tantalisingly out of reach",[8] while Greg Lehman wrote in Aboriginal History that Truganini "seems irrevocably condemned to remoteness by the limitations of the colonial record, the passing of centuries, and popular mythology attached to her life".[9] But despite these limitations in the available sources, Lehman praised Pybus' ability to connect with her subject and to write with empathy and nuance.[9] Writing in History Australia, Raymond Evans had a somewhat more positive assessment, writing that in Pybus' narrative Truganini was "no longer encased" and that the book makes the reader viscerally aware of the experience of colonisation for its victims.[10] Paul Daley, reviewing the book in The Guardian, also praised Pybus' ability to restore Truganini's perspective in her writing.[11] Billy Griffiths, reviewing the book in Australian Book Review, criticised the book's opacity about its sourcing and wrote that its use as a scholarly source was limited. But he nonetheless praised the book's writing for its "literary flair, compassion, and insight".[7] He also expressed scepticism about Pybus' decision not to engage with Truganini's afterlife, writing:

Other reviewers, however, approved of Pybus' choice to ignore Truganini's "afterlife". Lawson wrote that Pybus' narrative was an "attempt to rescue Truganini from the enormous condescension of colonial posterity".[8] Paul Daley wrote in the The Guardian that the book "goes a long way towards reinvesting Truganani with all that has been eclipsed by the trope of her 'tragedy'".[11] Awards

References

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||