|

V2 word order

In syntax, verb-second (V2) word order[1] is a sentence structure in which the finite verb of a sentence or a clause is placed in the clause's second position, so that the verb is preceded by a single word or group of words (a single constituent). Examples of V2 in English include (brackets indicating a single constituent):

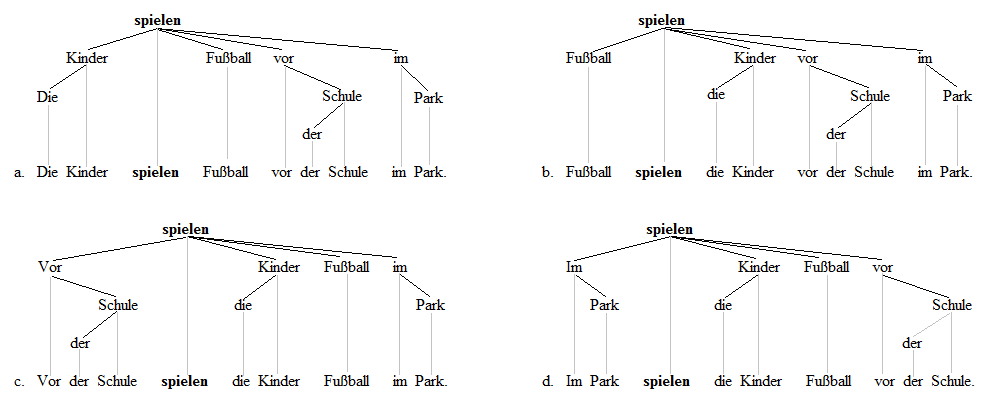

If English used V2 in all situations, then it would feature such sentences like: V2 word order is common in the Germanic languages and is also found in Northeast Caucasian Ingush, Uto-Aztecan O'odham, and fragmentarily in Romance Sursilvan (a Rhaeto-Romansh variety) and Finno-Ugric Estonian.[2] Of the Germanic family, English is exceptional in having predominantly SVO order instead of V2, although there are vestiges of the V2 phenomenon. Most Germanic languages do not normally use V2 order in embedded clauses, with a few exceptions. In particular, German, Dutch, and Afrikaans revert to VF (verb final) word order after a complementizer; Yiddish and Icelandic do, however, allow V2 in all declarative clauses: main, embedded, and subordinate. Kashmiri (an Indo-Aryan language) has V2 in 'declarative content clauses' but VF order in relative clauses. ExamplesThe example sentences in (1) from German illustrate the V2 principle, which allows any constituent to occupy the first position as long as the second position is occupied by the finite verb. Sentences (1a) through to (1d) have the finite verb spielten 'played' in second position, with various constituents occupying the first position: in (1a) the subject is in first position; in (1b) the object is; in (1c) the temporal modifier is in first position; and in (1d) the locative modifier is in first position. (1a) Die The-NOM-PL Kinder child-NOM-PL spielten play-PRET-3PL vor before der the-DAT-SG Schule school-DAT-SG im in the-DAT-SG Park park-DAT-SG Fußball. football/soccer-ACC-SG. The children played football/soccer in the park before school. (1b) Fußball Football/soccer-ACC-SG spielten play-PRET-3PL die the-NOM-PL Kinder child-NOM-PL vor before der the-DAT-SG Schule school-DAT-SG im in the-DAT-SG Park. park-DAT-SG. The children played football/soccer in the park before school. (1c) Vor Before der the-DAT-SG Schule school-DAT-SG spielten play-PRET-3PL die the-NOM-PL Kinder child-NOM-PL im in the-DAT-SG Park park-DAT-SG Fußball. football/soccer-ACC-SG. The children played football/soccer in the park before school. (1d) Im In the-DAT-SG Park park-DAT-SG spielten play-PRET-3PL die the-NOM-PL Kinder child-NOM-PL vor before der

Schule school-DAT-SG Fußball. football/soccer-ACC-SG. The children played football/soccer in the park before school. In this example, English is more straightforward to compare to a North Germanic language: The same inversions occur regularly in the North Germanic languages, and in Dutch, for that matter, but English uses the North Germanic word order apart from having lost the inversions in common use. If the same example in Norwegian were translated to English with the inversions intact: (2a) Barna child-DEF-PL spilte play-PRET fotball football/soccer i in parken park-DEF-SG før before skoletid. schooltime-SG. The children played football/soccer in the park before schooltime. (2b) Fotball football/soccer spilte play-PRET barna child-DEF-PL i in parken park-DEF-SG før before skoletid. schooltime-SG. Football/soccer played the children in the park before schooltime. (2c) Før Before skoletid schooltime spilte play-PRET barna child-DEF-PL fotball football/soccer i in parken. park-DEF-SG. Before schooltime played the children football/soccer in the park. (2d) I in parken park-DEF-SG spilte play-PRET barna child-DEF-PL fotball football/soccer før before skoletid. schooltime. In the park played the children football/soccer before schooltime. The caveat here (unlike in German) is that in languages without grammatical case, the form with the object first (2b) can only be used unambiguously when the object is unmistakable from the subject, such as if it is a personal pronoun, or as in this example, cannot meaningfully be the subject. In speech, such inversions are usually marked with emphasis: Apart from inversions that are obligatory in their grammatical context, such as "jeg tenker, derfor er jeg" (I think, therefore am I), when an inversion occurs for no other reason than emphasis, which is what opens up for possible ambiguity, the word in the emphasized position before the verb is usually also emphasized in speech. Classical accountsIn major theoretical research on V2 properties, researchers discussed that verb-final orders found in German and Dutch embedded clauses suggest an underlying SOV order with specific syntactic movement rules which change the underlying SOV order, deriving a surface form where the finite verb is in the second position of the clause.[3] We first see a "verb preposing" rule, which moves the finite verb to the left-most position in the sentence, then a "constituent preposing" rule, which moves a constituent in front of the finite verb. Following these two rules will always result with the finite verb in second position. "I like the man": (a) Ich I den the-ACC-SG Mann man-ACC-SG mag. like-PRES-1SG. I like the man. → Underlying form in modern German (b) Mag Like-PRES-1SG ich I den the-ACC-SG Mann. man-ACC-SG. I like the man. → Verb movement to left edge (c) Den The-ACC-SG Mann man-ACC-SG mag like-PRES-1SG ich. I. I like the man. → Constituent moved to left edge Non-finite verbs and embedded clausesNon-finite verbsThe V2 principle regulates the position of finite verbs only; its influence on non-finite verbs (infinitives, participles, etc.) is indirect. Non-finite verbs in V2 languages appear in varying positions depending on the language. In German and Dutch, for instance, non-finite verbs appear after the object (if one is present) in clause final position in main clauses (OV order). Swedish and Icelandic, in contrast, position non-finite verbs after the finite verb but before the object (if one is present) (VO order). That is, V2 operates on only the finite verb. Embedded clauses(In the following examples, finite verb forms are in bold, non-finite verb forms are in italics and subjects are underlined.) Germanic languages vary in the application of V2 order in embedded clauses. They fall into three groups. Swedish, Danish, Norwegian, FaroeseIn these languages, the word order of clauses is generally fixed in two patterns of conventionally numbered positions.[4] Both end with positions for (5) non-finite verb forms, (6) objects, and (7), adverbials. In main clauses, the V2 constraint holds. The finite verb must be in position (2) and sentence adverbs in position (4). The latter include words with meanings such as 'not' and 'always'. The subject may be position (1), but when a topical expression occupies the position, the subject is in position (3). In embedded clauses, the V2 constraint is absent. After the conjunction, the subject must immediately follow; it cannot be replaced by a topical expression. Thus, the first four positions are in the fixed order (1) conjunction, (2) subject, (3) sentence adverb, (4) finite verb The position of the sentence adverbs is important to those theorists who see them as marking the start of a large constituent within the clause. Thus the finite verb is seen as inside that constituent in embedded clauses, but outside that constituent in V2 main clauses. Swedish

Main clause Front Finite verb Subject Sentence adverb __ Non-finite verb Object Adverbial

Embedded clause __ Conjunction Subject Sentence adverb Finite verb Non-finite verb Object Adverbial

Main clause (a) I dag ville Lotte inte läsa tidningen

today wanted Lotte not read the newspaper

"Lotte didn't want to read the paper today."

Embedded clause (b) att Lotte inte ville koka kaffe i dag

that Lotte not wanted brew coffee today

"that Lotte didn't want to make coffee today."

Danish

So-called Perkerdansk is an example of a variety that does not follow the above. Norwegian

Faroese

GermanIn main clauses, the V2 constraint holds. As with other Germanic languages, the finite verb must be in the second position. However, any non-finite forms must be in final position. The subject may be in the first position, but when a topical expression occupies the position, the subject follows the finite verb. In embedded clauses, the V2 constraint does not hold. The finite verb form must be adjacent to any non-finite at the end of the clause. German grammarians traditionally divide sentences into fields. Subordinate clauses preceding the main clause are said to be in the first field (Vorfeld), clauses following the main clause in the final field (Nachfeld). In main clauses, the initial element (subject or topical expression) is said to be located in the first field, the V2 finite verb form in the left bracket, and any non-finite verb forms in the right bracket. German[5]

Dutch and AfrikaansV2 word order is used in main clauses, the finite verb must be in the second position. However, in subordinate clauses two word orders are possible for the verb clusters. Main clauses: Dutch[6]

This analysis suggests a close parallel between the V2 finite form in main clauses and the conjunctions in embedded clauses. Each is seen as an introduction to its clause-type, a function which some modern scholars have equated with the notion of specifier. The analysis is supported in spoken Dutch by the placement of clitic pronoun subjects. Forms such as ze cannot stand alone, unlike the full-form equivalent zij. The words to which they may be attached are those same introduction words: the V2 form in a main clause, or the conjunction in an embedded clause.[7]

Subordinate clauses: In Dutch subordinate clauses two word orders are possible for the verb clusters and are referred to as the "red": omdat ik heb gewerkt, "because I have worked": like in English, where the auxiliary verb precedes the past particle, and the "green": omdat ik gewerkt heb, where the past particle precedes the auxiliary verb, "because I worked have": like in German.[8] In Dutch, the green word order is the most used in speech, and the red is the most used in writing, particularly in journalistic texts, but the green is also used in writing as is the red in speech. Unlike in English however adjectives and adverbs must precede the verb: ''dat het boek groen is'', "that the book green is".

V2 in Icelandic and YiddishThese languages freely allow V2 order in embedded clauses. Icelandic

In more radical contrast with other Germanic languages, a third pattern exists for embedded clauses with the conjunction followed by the V2 order: front-finite verb-subject.[10]

Yiddish

Root clausesOne type of embedded clause with V2 following the conjunction is found throughout the Germanic languages, although it is more common in some than it is others. These are termed root clauses. They are declarative content clauses, the direct objects of so-called bridge verbs, which are understood to quote a statement. For that reason, they exhibit the V2 word order of the equivalent direct quotation. Danish

Swedish

This order is not possible with a statement with which the speaker does not agree.

Norwegian

German

Compare the normal embed-clause order after dass

Perspective effects on embedded V2There are a limited number of V2 languages that can allow for embedded verb movement for a specific pragmatic effect similar to that of English. This is due to the perspective of the speaker. Languages such as German and Swedish have embedded verb second. The embedded verb second in these kinds of languages usually occur after 'bridge verbs'.[12] (Bridge verbs are common verbs of speech and thoughts such as "say", "think", and "know", and the word "that" is not needed after these verbs. For example: I think he is coming.) (a) Jag I ska will säga say dig you att that jag I är am inte not ett a dugg dew intresserad. interested. (Swedish)

"I tell you that I am not the least bit interested." Based on an assertion theory, the perspective of a speaker is reaffirmed in embedded V2 clauses. A speaker's sense of commitment to or responsibility for V2 in embedded clauses is greater than a non-V2 in embedded clause.[13] This is the result of V2 characteristics. As shown in the examples below, there is a greater commitment to the truth in the embedded clause when V2 is in place. (a) Maria Maria-NOM-SG denkt, think-PRES-3SG, dass that Peter Peter-NOM-SG glücklich happy ist. be-PRES-3SG → In a non-V2 embedded clause, the speaker is only committed to the truth of the statement "Maria thinks ..." (b) Maria Maria-NOM-SG denkt, think-PRES-3SG, Peter Peter-NOM-SG ist be-PRES-3SG glücklich. happy. → In a V2 embedded clause, the speaker is committed to the truth of the statement "Maria thinks ..." and also the proposition "Peter is happy". VariationsVariations of V2 order such as V1 (verb-initial word order), V3 and V4 orders are widely attested in many Early Germanic and Medieval Romance languages. These variations are possible in the languages however it is severely restricted to specific contexts. V1 word orderV1 (verb-initial word order) is a type of structure that contains the finite verb as the initial clause element. In other words the verb appears before the subject and the object of the sentence. (a) Max y-il [s no' tx;i;] [o naq Lwin]. (Mayan)

PFV A3-see CLF dog CLF Pedro

'The dog saw Pedro.'

V3 word orderV3 (verb-third word order) is a variation of V2 in which the finite verb is in third position with two constituents preceding it. In V3, like in V2 word order, the constituents preceding the finite verb are not categorically restricted, as the constituents can be a DP, a PP, a CP and so on.[14] (a) [DP

Jedes every jahr] year [Pn

ich] I kauf buy-PRES-1SG mir me-DAT-SG bei at Deichmann Deichmann-DAT-SG (substandard German, „Kiezdeutsch“)

"Every year I buy (shoes) at Deichmann's"

(b) [PP

ab from jetzt] now [Pn

ich] I krieg get-PRES-SG immer always zwanzig twenty Euro euro-ACC-PL (substandard German)

"From now on, I always get twenty euros" Left edge filling trigger (LEFT)V2 is fundamentally derived from a morphological obligatory exponence effect at sentence level. The left edge filling trigger (LEFT) effects are usually seen in classical V2 languages such as Germanic languages and Old Romance languages. The left edge filling trigger is independently active in morphology as EPP effects are found in word-internal levels. The obligatory exponence derives from absolute displacement, ergative displacement and ergative doubling in inflectional morphology. In addition, second position rules in clitic second languages demonstrate post-syntactic rules of LEFT movement. Using the language Breton as an example, absence of a pre-tense expletive will allow for the LEFT to occur to avoid tense-first. The LEFT movement is free from syntactic rules which is evidence for a post-syntactic phenomenon. With the LEFT movement, V2 word order can be obtained as seen in the example below.[15] (a) Bez EXPL 'nevo Fin.[will.have] hennex he traou things (in Breton)

"He will have goods" In this Breton example, the finite head is phonetically realized and agrees with the category of the preceding element. The pre-tense "Bez" is used in front of the finite verb to obtain the V2 word order. (finite verb "nevo" is bolded). Syntactic verb secondIt is said that V2 patterns are a syntactic phenomenon and therefore have certain environments where it can and cannot be tolerated. Syntactically, V2 requires a left-peripheral head (usually C) with an occupied specifier and paired with raising the highest verb-auxiliary to that head. V2 is usually analyzed as the co-occurrence of these requirements, which can also be referred to as "triggers". The left-peripheral head, which is a requirement that causes the effect of V2, sets further requirements on a phrase XP that occupies the initial position, so that this phrase XP may always have specific featural characteristics. [16] EnglishModern English differs greatly in word order from other modern Germanic languages, but earlier English shared many similarities. For this reason, some scholars propose a description of Old English with V2 constraint as the norm. The history of English syntax is thus seen as a process of losing the constraint.[17] Old EnglishIn these examples, finite verb forms are in green, non-finite verb forms are in orange and subjects are blue. Main clausesa. Subject first Se the mæssepreost masspriest sceal shall manum people bodian preach þone the soþan true geleafan faith 'The mass priest shall preach the true faith to the people.' b. Question word first Hwi Why wolde would God God swa so lytles small þinges thing him him forwyrman deny 'Why would God deny him such a small thing?' c. Topic phrase first on in twam two þingum things hæfde has God God þæs the mannes man's sawle soul geododod endowed 'With two things God had endowed man's soul.' d. þa first þa then wæs was þæt the folc people þæs of-the micclan great welan prosperity ungemetlice excessively brucende partaking 'Then the people were partaking excessively of the great prosperity.' e. Negative word first Ne not sceal shall he he naht nothing unaliefedes unlawful don do 'He shall not do anything unlawful.' f. Object first Ðas these ðreo three ðing things forgifð gives God God he his gecorenum chosen 'These three things God gives to his chosen Position of objectIn examples b, c and d, the object of the clause precedes a non-finite verb form. Superficially, the structure is verb-subject-object- verb. To capture generalities, scholars of syntax and linguistic typology treat them as basically subject-object-verb (SOV) structure, modified by the V2 constraint. Thus Old English is classified, to some extent, as an SOV language. However, example a represents a number of Old English clauses with object following a non-finite verb form, with the superficial structure verb-subject-verb object. A more substantial number of clauses contain a single finite verb form followed by an object, superficially verb-subject-object. Again, a generalisation is captured by describing these as subject–verb–object (SVO) modified by V2. Thus Old English can be described as intermediate between SOV languages (like German and Dutch) and SVO languages (like Swedish and Icelandic). Effect of subject pronounsWhen the subject of a clause was a personal pronoun, V2 did not always operate. g. forðon therefore we we sceolan must mid with ealle all mod mind & and mægene power to to Gode God gecyrran turn 'Therefore, we must turn to God with all our mind and power

However, V2 verb-subject inversion occurred without exception after a question word or the negative ne, and with few exceptions after þa even with pronominal subjects. h. for for hwam what noldest not-wanted þu you ðe sylfe yourself me me gecyðan make-known þæt... that... 'wherefore would you not want to make known to me yourself that...' i. Ne not sceal shall he he naht nothing unaliefedes unlawful don do 'He shall not do anything unlawful.' j. þa then foron sailed hie they mid with þrim three scipum ships ut out 'Then they sailed out with three ships.' Inversion of a subject pronoun also occurred regularly after a direct quotation.[18] k. "Me to me is," is cwæð said hēo she Þīn your cyme coming on in miclum much ðonce" thankfulness '"Your coming," she said, "is very gratifying to me".' Embedded clausesEmbedded clauses with pronoun subjects were not subject to V2. Even with noun subjects, V2 inversion did not occur. l. ...þa ða ...when his his leorningcnichtas disciples hine him axodon asked for for hwæs whose synnum sins se the man man wurde became swa thus blind blind acenned

'...when his disciples asked him for whose sins the man was thus born blind' Yes–no questionsIn a similar clause pattern, the finite verb form of a yes–no question occupied the first position m. Truwast trust ðu you nu now þe you selfum self and and þinum your geferum companions bet better þonne than ðam the apostolum...? apostles 'Do you now trust yourself and your companions better than the apostles...?' Middle EnglishContinuityEarly Middle English generally preserved V2 structure in clauses with nominal subjects. a. Topic phrase first On in þis this gær year wolde wanted þe the king king Stephne Stephen tæcen seize Rodbert Robert 'During this year King Stephen wanted to seize Robert.' b. Nu first Nu now loke look euerich every man man toward to himseleun himself 'Now it's for every man to look to himself.' As in Old English, V2 inversion did not apply to clauses with pronoun subjects. c. Topic phrase first bi by þis this ȝe you mahen may seon see ant and witen... know d. Object first alle all ðese those bebodes commandments ic I habbe have ihealde kept fram from childhade childhood ChangeLate Middle English texts of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries show increasing incidence of clauses without the inversion associated with V2. e. Topic adverb first sothely Truly se the ryghtwyse righteous sekys seeks þe the loye joy and... and... f. Topic phrase first And And by by þis this same same skyle skill hop hope and and sore sorrow shulle shall jugen judge us us Negative clauses were no longer formed with ne (or na) as the first element. Inversion in negative clauses was attributable to other causes. g. Wh- question word first why why ordeyned ordained God God not not such such ordre order 'Why did God not ordain such an order?' (not follows noun phrase subject) h. why why shulde should he he not... not

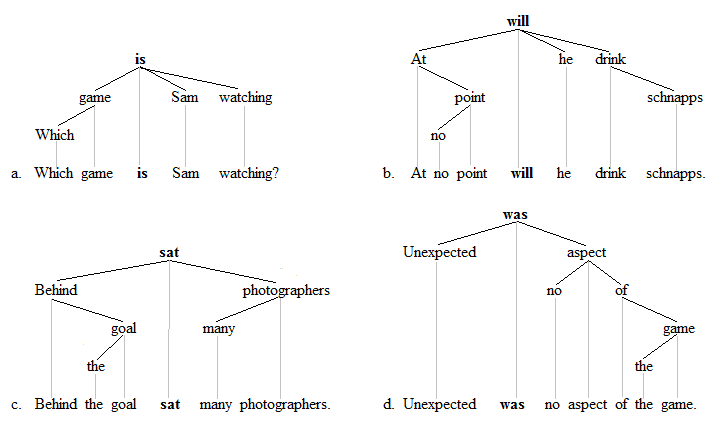

(not precedes pronoun subject) i. There first Ther there nys not-is nat not oon one kan can war aware by by other other be be 'There is not a single person who learns from the mistakes of others' j. Object first He He was was despeyred; in despair; no thyng nothing dorste dared he he seye say Vestiges in Modern EnglishAs in earlier periods, Modern English normally has subject-verb order in declarative clauses and inverted verb-subject order[19] in interrogative clauses. However these norms are observed irrespective of the number of clause elements preceding the verb. Classes of verbs in Modern English: auxiliary and lexicalInversion in Old English sentences with a combination of two verbs could be described in terms of their finite and non-finite forms. The word which participated in inversion was the finite verb; the verb which retained its position relative to the object was the non-finite verb. In most types of Modern English clause, there are two verb forms, but the verbs are considered to belong to different syntactic classes. The verbs which participated in inversion have evolved to form a class of auxiliary verbs which may mark tense, aspect and mood; the remaining majority of verbs with full semantic value are said to constitute the class of lexical verbs. The exceptional type of clause is that of declarative clause with a lexical verb in a present simple or past simple form. QuestionsLike Yes/No questions, interrogative Wh- questions are regularly formed with inversion of subject and auxiliary. Present Simple and Past Simple questions are formed with the auxiliary do, a process known as do-support.

With topic adverbs and adverbial phrasesIn certain patterns similar to Old and Middle English, inversion is possible. However, this is a matter of stylistic choice, unlike the constraint on interrogative clauses. negative or restrictive adverbial first

comparative adverb or adjective first

After the preceding classes of adverbial, only auxiliary verbs, not lexical verbs, participate in inversion locative or temporal adverb first

prepositional phrase first

After the two latter types of adverbial, only one-word lexical verb forms (Present Simple or Past Simple), not auxiliary verbs, participate in inversion, and only with noun-phrase subjects, not pronominal subjects. Direct quotationsWhen the object of a verb is a verbatim quotation, it may precede the verb, with a result similar to Old English V2. Such clauses are found in storytelling and in news reports.

Declarative clauses without inversionCorresponding to the above examples, the following clauses show the normal Modern English subject-verb order. Declarative equivalents

Equivalents without topic fronting

FrenchModern French is a subject-verb-object (SVO) language like other Romance languages (though Latin was a subject-object-verb language). However, V2 constructions existed in Old French and were more common than in other early Romance language texts. It has been suggested that this may be due to influence from the Germanic Frankish language.[20] Modern French has vestiges of the V2 system similar to those found in modern English. The following sentences have been identified as possible examples of V2 syntax in Old French:[21]

Old FrenchSimilarly to Modern French, Old French allows a range of constituents to precede the finite verb in the V2 position. (1) Il He oste removes.3sg ses his armes weapons 'He removes his weapons' Old OccitanA language that is compared to Old French is Old Occitan, which is said to be the sister of Old French. Although the two languages are thought to be sister languages, Old Occitan exhibits a relaxed V2 whereas Old French has a much more strict V2. However, the differences between the two languages extend past V2 and also differ in a variation of V2, which is V3. In both language varieties, occurrence of V3 can be triggered by the presence of an initial frame-setting clause or adverbial (1). (1) Car For s'il if-he ne NEG me me.CL= garde look.3SG de of pres, close je I ne NEG dout doubt.1SG mie NEG 'Since he watches me so closely, I do not doubt' Other languagesKotgarhi and KochiIn his 1976 three-volume study of two languages of Himachal Pradesh, Hendriksen reports on two intermediate cases: Kotgarhi and Kochi. Although neither language shows a regular V 2 pattern, they have evolved to the point that main and subordinate clauses differ in word order and auxiliaries may separate from other parts of the verb: (a) hyunda-baassie winter-after jaa goes gõrmi summer hõ-i become-GER (in Kotgarhi)

"After winter comes summer." (Hendriksen III:186) Hendriksen reports that relative clauses in Kochi show a greater tendency to have the finite verbal element in clause-final position than matrix clauses do (III:188). IngushIn Ingush, "for main clauses, other than episode-initial and other all-new ones, verb-second order is most common. The verb, or the finite part of a compound verb or analytic tense form (i.e. the light verb or the auxiliary), follows the first word or phrase in the clause."[22] (a) muusaa Musa vy V.PROG hwuona 2sg.DAT telefon telephone jettazh striking 'Musa is telephoning you.' O'odhamO'odham has relatively free V2 word order within clauses; for example, all of the following sentences mean "the boy brands the pig":[23] ceoj ʼo g ko:jĭ ceposid

ko:jĭ ʼo g ceoj ceposid

ceoj ʼo ceposid g ko:jĭ

ko:jĭ ʼo ceposid g ceoj

ceposid ʼo g ceoj g ko:jĭ

ceposid ʼo g ko:jĭ g ceoj

The finite verb is "'o" and appears after a constituent in the second position. Despite the general freedom of sentence word order, O'odham is fairly strictly V2 in its placement of the auxiliary verb (in the sentences above, it is ʼo; in the sentences below, it is ʼañ): Affirmative: cipkan ʼañ = "I am working"

Negative: pi ʼañ cipkan = "I am not working" [not *pi cipkan ʼañ]

SursilvanAmong dialects of the Romansh, V2 word order is limited to Sursilvan, the insertion of entire phrases between auxiliary verbs and participles occurs, as in 'Cun Mariano Tschuor ha Augustin Beeli discurriu ' ('Mariano Tschuor has spoken with Augustin Beeli'), as compared to Engadinese 'Cun Rudolf Gasser ha discurrü Gion Peider Mischol' ('Rudolf Gasser has spoken with Gion Peider Mischol'.)[24] The constituent that is bounded by the auxiliary, ha, and the participle, discurriu, is known as a Satzklammer or 'verbal bracket'. EstonianIn Estonian, V2 is very frequent in the literate register but less frequent in the spoken register. When V2 occurs, it is found in main clauses as illustrated in (1). (1) Kiiresti quickly lahku-s-id leave-PST-3PL õpilase-d student-NOM.PL koolimaja-st. schoolhouse-ELA 'The students departed quickly from the schoolhouse.' Unlike Germanic V2 languages, Estonian has several instances where V2 word order is not attested in embedded clauses, such as wh-interrogatives (2), exclamatives (3), and non-subject-initial clauses (4).[25] (2) Kes who.NOM mei-le we-ALL täna today külla village/visit.ILL tule-b? come-PRS.3SG 'Who will visit us today?' (3) Küll EMP ta s/he.NOM täna today tule-b. come-PRS.3SG 'S/he's sure to come today!' (4) Täna today ta s/he.NOM mei-le we-ALL külla village/visit.ILL ei not tule. come 'Today s/he won't come to visit us.' WelshIn Welsh, V2 word order is found in Middle Welsh but not in Old and Modern Welsh, which have only verb-initial order.[26] Middle Welsh displays three characteristics of V2 grammar: (1) A finite verb in the C-domain

(2) The constituent preceding the verb can be any constituent (often driven by pragmatic features).

(3) Only one constituent preceding the verb in subject position

As can be seen in the following examples of V2 in Welsh, there is only one constituent preceding the finite verb, but any kind of constituent (such as a noun phrase NP, adverb phrase AP and preposition phrase PP) can occur in this position. (a) [DP

'r the guyrda nobles a] PRT doethant came y gyt. together. "The nobles came together" (b) [DP

deu two drws door a] PRT welynt saw yn PRED agoret. open. "They saw two doors that were open" (c) [AdvP

yn PRED diannot immediate y] PRT doeth came tan fire o from r the nef. heaven. "Immediately there came fire from the heavens" (d) [PP

y to r the neuad hall y] PRT kyrchyssant. went. "They made for the hall" Middle Welsh can also exhibit variations of V2 such as cases of V1 (verb-initial word order) and V3 orders. However, these variations are restricted to specific contexts, such as in sentences with impersonal verbs, imperatives, answers or direct responses to questions or commands and idiomatic sayings. A preverbal particle can also precede the verb in V2, but such sentences are limited as well. WymysorysWymysory is classified as a West Germanic language but can exhibit various Slavonic characteristics. It is argued that Wymysorys enables its speaker to operate between two word order system, which represent both forces driving its grammar: Germanic and Slavonic. The Germanic system is not as flexible and allows for V2 to exist in it form, but the Slavonic system is relatively free. The rigid word order in the Germanic system causes the placement of the verb to be determined by syntactic rules in which V2 is commonly respected.[27] Wymysory, like with other languages that exhibit V2, has the finite verb in second position, and a constituent of any category precedes the verb such as DP, PP, AP and so on. (a) [DP

Der The klop] man kuzt speaks wymyioerys. Wymysorys. "The man speaks Wymysorys" (b) [DP

Dos This bihɫa] book hot had yh I gyśrejwa. written. "I had written that book" (c) [PP

Fjyr For ejn] him ej is do. this. "This is for him" Classical PortugueseV2 word order existed in Classical Portuguese much longer than in other Romance languages. Although Classical Portuguese was a V2 language, V1 occurred more frequently and so it is argued whether or not Classical Portuguese really is a V2-like language. However, Classical Portuguese was a relaxed V2 language, and V2 co-exist with its variations: V1 and V3. Classical Portuguese had a strong relationship between V1 and V2 since V2 clauses were derived from V1 clauses. In languages where both V1 and V2 exist, both patterns depend on the movement of the verb to a high position of the CP layer. The difference is whether or not a phrase is moved to a preverbal position.[28] Although V1 occurred more frequently in Classical Portuguese, V2 was more frequently found in matrix clauses. Post-verbal subjects could also occupy a high position in the clause and precede VP adverbs. In (1) and (2), it can be seen that the adverb 'bem' could be before or after the post-verbal subject. (1) E and nos in-the gasalhados welcome e and abraços greetings mostraram showed os the cardeais cardinals legados delegates 'In the welcome and greetings the cardinal delegates showed this satisfaction well.' (2) E and quadra-lhe fits-CL.3.DAT bem well o the nome name de of Piemonte... Piemonte 'And the name of Piemonte fits it well...' In (2), the post-verbal subject is understood as an informational focus, but the same cannot be said for (1) because the different positions determine how the subject is interpreted. Structural analysisVarious structural analyses of V2 have been developed, including within the model of dependency grammar and generative grammar. Dependency grammarDependency grammar (DG) can accommodate the V2 phenomenon simply by stipulating that one and only one constituent must be a predependent of the finite verb (i.e. a dependent which precedes its head) in declarative (matrix) clauses (in this, Dependency Grammar assumes only one clausal level and one position of the verb, instead of a distinction between a VP-internal and a higher clausal position of the verb as in Generative Grammar, cf. the next section).[29] On this account, the V2 principle is violated if the finite verb has more than one predependent or no predependent at all. The following DG structures of the first four German sentences above illustrate the analysis (the sentence means 'The kids play soccer in the park before school'): The finite verb spielen is the root of all clause structure. The V2 principle requires that this root have a single predependent, which it does in each of the four sentences. The four English sentences above involving the V2 phenomenon receive the following analyses: Generative grammarIn the theory of Generative Grammar, the verb second phenomenon has been described as an application of X-bar theory. The combination of a first position for a phrase and a second position for a single verb has been identified as the combination of specifier and head of a phrase. The part after the finite verb is then the complement. While the sentence structure of English is usually analysed in terms of three levels, CP, IP, and VP, in German linguistics the consensus has emerged that there is no IP in German.[30]  The VP (verb phrase) structure assigns position and functions to the arguments of the verb. Hence, this structure is shaped by the grammatical properties of the V (verb) which heads the structure. The CP (complementizer phrase) structure incorporates the grammatical information which identifies the clause as declarative or interrogative, main or embedded. The structure is shaped by the abstract C (complementiser) which is considered the head of the structure. In embedded clauses the C position accommodates complementizers. In German declarative main clauses, C hosts the finite verb. Thus the V2 structure is analysed as

In embedded clauses, the C position is occupied by a complementizer. In most Germanic languages (but not in Icelandic or Yiddish), this generally prevents the finite verb from moving to C.

This analysis does not provide a structure for the instances in some language of root clauses after bridge verbs.

The solution is to allow verbs such as ved to accept a clause with a second (recursive) CP.[31]

See alsoNotes

Literature

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||