|

Gothic fiction

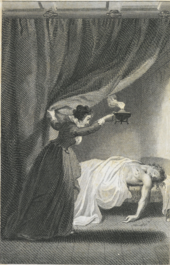

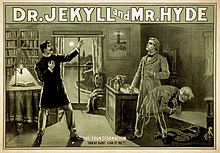

Gothic fiction, sometimes called Gothic horror (primarily in the 20th century), is a loose literary aesthetic of fear and haunting. The name refers to Gothic architecture of the European Middle Ages, which was characteristic of the settings of early Gothic novels. The first work to call itself Gothic was Horace Walpole's 1764 novel The Castle of Otranto, later subtitled "A Gothic Story". Subsequent 18th-century contributors included Clara Reeve, Ann Radcliffe, William Thomas Beckford, and Matthew Lewis. The Gothic influence continued into the early 19th century; works by the Romantic poets, like Samuel Taylor Coleridge and Lord Byron, and novelists such as Mary Shelley, Charles Maturin, Walter Scott and E. T. A. Hoffmann frequently drew upon gothic motifs in their works. The early Victorian period continued the use of gothic aesthetic in novels by Charles Dickens and the Brontë sisters, as well as works by the American writers Edgar Allan Poe and Nathaniel Hawthorne. Later well-known works were Dracula by Bram Stoker, Richard Marsh's The Beetle and Robert Louis Stevenson's Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde. 20th-century contributors include Daphne du Maurier, Stephen King, Shirley Jackson, Anne Rice, and Toni Morrison. Characteristics Gothic fiction is characterized by an environment of fear, the threat of supernatural events, and the intrusion of the past upon the present.[1][2] The setting typically includes physical reminders of the past, especially through ruined buildings which stand as proof of a previously thriving world which is decaying in the present.[3] Characteristic settings in the 18th and 19th centuries include castles, religious buildings such as monasteries and convents, and crypts. The atmosphere is typically claustrophobic, and common plot elements include vengeful persecution, imprisonment, and murder.[1] The depiction of horrible events in Gothic fiction often serves as a metaphorical expression of psychological or social conflicts.[2] The form of a Gothic story is usually discontinuous and convoluted, often incorporating tales within tales, changing narrators, and framing devices such as discovered manuscripts or interpolated histories.[4] Other characteristics, regardless of relevance to the main plot, can include sleeplike and deathlike states, live burials, doubles, unnatural echoes or silences, the discovery of obscured family ties, unintelligible writings, nocturnal landscapes, remote locations,[5] and dreams.[4] Especially in the late 19th century, Gothic fiction often involved demons and demonic possession, ghosts, and other kinds of evil spirits.[5] Gothic fiction often moves between "high culture" and "low" or "popular culture".[2][clarification needed] Role of architecture  Gothic literature is strongly associated with the Gothic Revival architecture of the same era. English Gothic writers often associated medieval buildings with what they saw as a dark and terrifying period, marked by harsh laws enforced by torture and with mysterious, fantastic, and superstitious rituals. Similar to the Gothic Revivalists' rejection of the clarity and rationalism of the Neoclassical style of the Enlightened Establishment, the literary Gothic embodies an appreciation of the joys of extreme emotion, the thrills of fearfulness and awe inherent in the sublime, and a quest for atmosphere. Gothic ruins invoke multiple linked emotions by representing inevitable decay and the collapse of human creations – hence the urge to add fake ruins as eyecatchers in English landscape parks. Placing a story in a Gothic building serves several purposes. It inspires feelings of awe, implies that the story is set in the past, gives an impression of isolation or dissociation from the rest of the world, and conveys religious associations. Setting the novel in a Gothic castle was meant to imply a story set in the past and shrouded in darkness. The architecture often served as a mirror for the characters and events of the story.[7] The buildings in The Castle of Otranto, for example, are riddled with tunnels that characters use to move back and forth in secret. This movement mirrors the secrets surrounding Manfred's possession of the castle and how it came into his family.[8] The Female GothicFrom the castles, dungeons, forests, and hidden passages of the Gothic novel genre emerged female Gothic. Guided by the works of authors such as Ann Radcliffe, Mary Shelley, and Charlotte Brontë, the female Gothic allowed women's societal and sexual desires to be introduced. In many respects, the novel's intended reader of the time was the woman who, even as she enjoyed such novels, felt she had to "[lay] down her book with affected indifference, or momentary shame,"[9] according to Jane Austen. The Gothic novel shaped its form for woman readers to "turn to Gothic romances to find support for their own mixed feelings."[10] Female Gothic narratives focus on such topics as a persecuted heroine fleeing from a villainous father and searching for an absent mother. At the same time, male writers tend towards the masculine transgression of social taboos. The emergence of the ghost story gave women writers something to write about besides the common marriage plot, allowing them to present a more radical critique of male power, violence, and predatory sexuality.[11] Authors such as Mary Robinson and Charlotte Dacre however, present a counter to the naive and persecuted heroines usually featured in female Gothic of the time, and instead feature more sexually assertive heroines in their works.[12] When the female Gothic coincides with the explained supernatural, the natural cause of terror is not the supernatural, but female disability and societal horrors: rape, incest, and the threatening control of a male antagonist. Female Gothic novels also address women's discontent with patriarchal society, their difficult and unsatisfying maternal position, and their role within that society. Women's fears of entrapment in the domestic, their bodies, marriage, childbirth, or domestic abuse commonly appear in the genre. After the characteristic Gothic Bildungsroman-like plot sequence, female Gothic allowed readers to grow from "adolescence to maturity"[13] in the face of the realized impossibilities of the supernatural. As protagonists such as Adeline in The Romance of the Forest learn that their superstitious fantasies and terrors are replaced by natural cause and reasonable doubt, the reader may grasp the heroine's true position: "The heroine possesses the romantic temperament that perceives strangeness where others see none. Her sensibility, therefore, prevents her from knowing that her true plight is her condition, the disability of being female."[13] HistoryPrecursors

— Lines from Shakespeare's Hamlet

The components that would eventually combine into Gothic literature had a rich history by the time Walpole presented a fictitious medieval manuscript in The Castle of Otranto in 1764. The plays of William Shakespeare, in particular, were a crucial reference point for early Gothic writers, in both an effort to bring credibility to their works, and to legitimize the emerging genre as serious literature to the public.[14] Tragedies such as Hamlet, Macbeth, King Lear, Romeo and Juliet, and Richard III, with plots revolving around the supernatural, revenge, murder, ghosts, witchcraft, and omens, written in dramatic pathos, and set in medieval castles, were a huge influence upon early Gothic authors, who frequently quote, and make allusions to Shakespeare's works.[15] John Milton's Paradise Lost (1667) was also very influential among Gothic writers, who were especially drawn to the tragic anti-hero character Satan, who became a model for many charismatic Gothic villains and Byronic heroes. Milton's "version of the myth of the fall and redemption, creation and decreation, is, as Frankenstein again reveals, an important model for Gothic plots."[16] Alexander Pope, who had a considerable influence on Walpole, was the first significant poet of the 18th century to write a poem in an authentic Gothic manner.[17] Eloisa to Abelard (1717), a tale of star-crossed lovers, one doomed to a life of seclusion in a convent, and the other in a monastery, abounds in gloomy imagery, religious terror, and suppressed passion. The influence of Pope's poem is found throughout 18th-century Gothic literature, including the novels of Walpole, Radcliffe, and Lewis.[18] Gothic literature is often described with words such as "wonder" and "terror."[19] This sense of wonder and terror that provides the suspension of disbelief so important to the Gothic—which, except for when it is parodied, even for all its occasional melodrama, is typically played straight, in a self-serious manner—requires the imagination of the reader to be willing to accept the idea that there might be something "beyond that which is immediately in front of us." The mysterious imagination necessary for Gothic literature to have gained any traction had been growing for some time before the advent of the Gothic. The need for this came as the known world was becoming more explored, reducing the geographical mysteries of the world. The edges of the map were filling in, and no dragons were to be found. The human mind required a replacement.[20] Clive Bloom theorizes that this void in the collective imagination was critical in developing the cultural possibility for the rise of the Gothic tradition.[21] The setting of most early Gothic works was medieval, but this was a common theme long before Walpole. In Britain especially, there was a desire to reclaim a shared past. This obsession frequently led to extravagant architectural displays, such as Fonthill Abbey, and sometimes mock tournaments were held. It was not merely in literature that a medieval revival made itself felt, and this, too, contributed to a culture ready to accept a perceived medieval work in 1764.[20] The Gothic often uses scenery of decay, death, and morbidity to achieve its effects (especially in the Italian Horror school of Gothic). However, Gothic literature was not the origin of this tradition; it was far older. The corpses, skeletons, and churchyards so commonly associated with early Gothic works were popularized by the Graveyard poets. They were also present in novels such as Daniel Defoe's A Journal of the Plague Year, which contains comical scenes of plague carts and piles of corpses. Even earlier, poets like Edmund Spenser evoked a dreary and sorrowful mood in such poems as Epithalamion.[20] All aspects of pre-Gothic literature occur to some degree in the Gothic, but even taken together, they still fall short of true Gothic.[20] What needed to be added was an aesthetic to tie the elements together. Bloom notes that this aesthetic must take the form of a theoretical or philosophical core, which is necessary to "sav[e] the best tales from becoming mere anecdote or incoherent sensationalism."[22] In this case, the aesthetic needed to be emotional, and was finally provided by Edmund Burke's 1757 work, A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful, which "finally codif[ied] the gothic emotional experience."[23] Specifically, Burke's thoughts on the Sublime, Terror, and Obscurity were most applicable. These sections can be summarized thus: the Sublime is that which is or produces the "strongest emotion which the mind is capable of feeling"; Terror most often evoked the Sublime; and to cause Terror, we need some amount of Obscurity – we can't know everything about that which is inducing Terror – or else "a great deal of the apprehension vanishes"; Obscurity is necessary to experience the Terror of the unknown.[20] Bloom asserts that Burke's descriptive vocabulary was essential to the Romantic works that eventually informed the Gothic. The birth of Gothic literature was thought to have been influenced by political upheaval. Researchers linked its birth with the English Civil War, culminating in the Jacobite rising of 1745 which was more recent to the first Gothic novel (1764). The collective political memory and any deep cultural fears associated with it likely contributed to early Gothic villains as literary representatives of defeated Tory barons or Royalists "rising" from their political graves in the pages of early Gothic novels to terrorize the bourgeois reader of late eighteenth-century England.[24][25][26][27] Eighteenth-century Gothic novels The first work to call itself "Gothic" was Horace Walpole's The Castle of Otranto (1764).[1] The first edition presented the story as a translation of a sixteenth-century manuscript and was widely popular.[28] Walpole, in the second edition, revealed himself as the author which adding the subtitle "A Gothic Story." The revelation prompted a backlash from readers, who considered it inappropriate for a modern author to write a supernatural story in a rational age.[29] Initiating a literary genre, Walpole's Gothic tale inspired many contemporary imitators, including Clara Reeve's The Old English Baron (1778), with Reeve writing in the preface: "This Story is the literary offspring of The Castle of Otranto".[28] Like Reeve, the 1780s saw more writers attempting his combination of supernatural plots with emotionally realistic characters. Examples include Sophia Lee's The Recess (1783–5) and William Beckford's Vathek (1786).[30]  At the height of the Gothic novel's popularity in the 1790s, the genre was almost synonymous with Ann Radcliffe, whose works were highly anticipated and widely imitated. The Romance of the Forest (1791) and The Mysteries of Udolpho (1794) were particularly popular.[30] In an essay on Radcliffe, Walter Scott writes of the popularity of Udolpho at the time, "The very name was fascinating, and the public, who rushed upon it with all the eagerness of curiosity, rose from it with unsated appetite. When a family was numerous, the volumes flew, and were sometimes torn from hand to hand."[31] Radcliffe's novels were often seen as the feminine and rational opposite of a more violently horrifying male Gothic associated with Matthew Lewis. Radcliffe's final novel, The Italian (1797), responded to Lewis's The Monk (1796).[2] Radcliffe and Lewis have been called "the two most significant Gothic novelists of the 1790s."[32]  The popularity and influence of The Mysteries of Udolpho and The Monk saw the rise of shorter and cheaper versions of Gothic literature in the forms of Gothic bluebooks and chapbooks, which in many cases were plagiarized and abridgments of well known Gothic novels.[33] The Monk in particular, with its immoral and sensational content, saw many plagiarized copies, and was notably drawn from in the cheaper pamphlets.[34] Other notable Gothic novels of the 1790s include William Godwin's Caleb Williams (1794), Regina Maria Roche's Clermont (1798), and Charles Brockden Brown's Wieland (1798), as well as large numbers of anonymous works published by the Minerva Press established by William Lane at Leadenhall Street, London in 1790.[30] In continental Europe, Romantic literary movements led to related Gothic genres such as the German Schauerroman and the French Roman noir.[35][36] Eighteenth-century Gothic novels were typically set in a distant past and (for English novels) a distant European country, but without specific dates or historical figures that characterized the later development of historical fiction.[37]  The saturation of Gothic-inspired literature during the 1790s was referred to in a letter by Samuel Taylor Coleridge, writing on 16 March 1797, "indeed I am almost weary of the Terrible, having been a hireling in the Critical Review for the last six or eight months – I have been reviewing the Monk, the Italian, Hubert de Sevrac &c &c &c – in all of which dungeons, and old castles, & solitary Houses by the Sea Side & Caverns & Woods & extraordinary characters & all the tribe of Horror & Mystery, have crowded on me – even to surfeiting."[38] The excesses, stereotypes, and frequent absurdities of the Gothic genre made it rich territory for satire.[39] Historian Rictor Norton notes that satire of Gothic literature was common from 1796 until the 1820s, including early satirical works such as The New Monk (1798), More Ghosts! (1798) and Rosella, or Modern Occurrences (1799). Gothic novels themselves, according to Norton, also possess elements of self-satire, "By having profane comic characters as well as sacred serious characters, the Gothic novelist could puncture the balloon of the supernatural while at the same time affirming the power of the imagination."[40] After 1800 there was a period in which Gothic parodies outnumbered forthcoming Gothic novels.[41] In The Heroine by Eaton Stannard Barrett (1813), Gothic tropes are exaggerated for comic effect.[42] In Jane Austen's novel Northanger Abbey (1818), the naive protagonist, a female named Catherine, conceives herself as a heroine of a Radcliffean romance and imagines murder and villainy on every side. However, the truth turns out to be much more prosaic. This novel is also noted for including a list of early Gothic works known as the Northanger Horrid Novels.[43] Second generation or Jüngere RomantikThe poetry, romantic adventures, and character of Lord Byron—characterized by his spurned lover Lady Caroline Lamb as "mad, bad and dangerous to know"—were another inspiration for the Gothic novel, providing the archetype of the Byronic hero. For example, Byron is the title character in Lady Caroline's Gothic novel Glenarvon (1816).  Byron was also the host of the celebrated ghost-story competition involving himself, Percy Bysshe Shelley, Mary Shelley, and John William Polidori at the Villa Diodati on the banks of Lake Geneva in the summer of 1816. This occasion was productive of both Mary Shelley's Frankenstein, or, The Modern Prometheus (1818), and Polidori's short story "The Vampyre" (1819), featuring the Byronic Lord Ruthven. "The Vampyre" has been accounted by cultural critic Christopher Frayling as one of the most influential works of fiction ever written and spawned a craze for vampire fiction and theatre (and, latterly, film) that has not ceased to this day.[44] Although clearly influenced by the Gothic tradition, Mary Shelley's novel is often considered the first science fiction novel, despite the novel's lack of any scientific explanation for the animation of Frankenstein's monster and the focus instead on the moral dilemmas and consequences of such a creation. John Keats' La Belle Dame sans Merci (1819) and Isabella, or the Pot of Basil (1820) feature mysteriously fey ladies.[45] In the latter poem, the names of the characters, the dream visions, and the macabre physical details are influenced by the novels of premiere Gothicist Ann Radcliffe.[45] Although ushering in the historical novel, and turning popularity away from Gothic fiction, Walter Scott frequently employed Gothic elements in his novels and poetry.[46] Scott drew upon oral folklore, fireside tales, and ancient superstitions, often juxtaposing rationality and the supernatural. Novels such as The Bride of Lammermoor (1819), in which the characters' fates are decided by superstition and prophecy, or the poem Marmion (1808), in which a nun is walled alive inside a convent, illustrate Scott's influence and use of Gothic themes.[47][48] A late example of a traditional Gothic novel is Melmoth the Wanderer (1820) by Charles Maturin, which combines themes of anti-Catholicism with an outcast Byronic hero.[49] Jane C. Loudon's The Mummy! (1827) features standard Gothic motifs, characters, and plot, but with one significant twist; it is set in the twenty-second century and speculates on fantastic scientific developments that might have occurred three hundred years in the future, making it and Frankenstein among the earliest examples of the science fiction genre developing from Gothic traditions.[50] During two decades, the most famous author of Gothic literature in Germany was the polymath E. T. A. Hoffmann. Lewis's The Monk influenced and even mentioned it in his novel The Devil's Elixirs (1815). The novel explores the motive of Doppelgänger, a term coined by another German author and supporter of Hoffmann, Jean-Paul, in his humorous novel Siebenkäs (1796–1797). He also wrote an opera based on Friedrich de la Motte Fouqué's Gothic story Undine (1816), for which de la Motte Fouqué wrote the libretto.[51] Aside from Hoffmann and de la Motte Fouqué, three other important authors from the era were Joseph Freiherr von Eichendorff (The Marble Statue, 1818), Ludwig Achim von Arnim (Die Majoratsherren, 1819), and Adelbert von Chamisso (Peter Schlemihls wundersame Geschichte, 1814).[52] After them, Wilhelm Meinhold wrote The Amber Witch (1838) and Sidonia von Bork (1847). In Spain, the priest Pascual Pérez Rodríguez was the most diligent novelist in the Gothic way, closely aligned to the supernatural explained by Ann Radcliffe.[53] At the same time, the poet José de Espronceda published The Student of Salamanca (1837–1840), a narrative poem that presents a horrid variation on the Don Juan legend.  In Russia, authors of the Romantic era include Antony Pogorelsky (penname of Alexey Alexeyevich Perovsky), Orest Somov, Oleksa Storozhenko,[54] Alexandr Pushkin, Nikolai Alekseevich Polevoy, Mikhail Lermontov (for his work Stuss), and Alexander Bestuzhev-Marlinsky.[55] Pushkin is particularly important, as his 1833 short story The Queen of Spades was so popular that it was adapted into operas and later films by Russian and foreign artists. Some parts of Mikhail Yuryevich Lermontov's A Hero of Our Time (1840) are also considered to belong to the Gothic genre, but they lack the supernatural elements of other Russian Gothic stories. The following poems are also now considered to belong to the Gothic genre: Meshchevskiy's "Lila", Katenin's "Olga", Pushkin's "The Bridegroom", Pletnev's "The Gravedigger" and Lermontov's Demon (1829–1839).[56] The key author of the transition from Romanticism to Realism, Nikolai Vasilievich Gogol, who was also one of the most important authors of Romanticism, produced a number of works that qualify as Gothic fiction. Each of his three short story collections features a number of stories that fall within the Gothic genre or contain Gothic elements. They include "Saint John's Eve" and "A Terrible Vengeance" from Evenings on a Farm Near Dikanka (1831–1832), "The Portrait" from Arabesques (1835), and "Viy" from Mirgorod (1835). While all are well known, the latter is probably the most famous, having inspired at least eight film adaptations (two now considered lost), one animated film, two documentaries, and a video game. Gogol's work differs from Western European Gothic fiction, as his cultural influences drew on Ukrainian folklore, the Cossack lifestyle, and, as a religious man, Orthodox Christianity.[57][58] Other relevant authors of this era include Vladimir Fyodorovich Odoevsky (The Living Corpse, written 1838, published 1844, The Ghost, The Sylphide, as well as short stories), Count Aleksey Konstantinovich Tolstoy (The Family of the Vourdalak, 1839, and The Vampire, 1841), Mikhail Zagoskin (Unexpected Guests), Józef Sękowski/Osip Senkovsky (Antar), and Yevgeny Baratynsky (The Ring).[55] Nineteenth-century Gothic fiction By the Victorian era, Gothic had ceased to be the dominant genre for novels in England, partly replaced by more sedate historical fiction. However, Gothic short stories continued to be popular, published in magazines or as small chapbooks called penny dreadfuls.[1] The most influential Gothic writer from this period was the American Edgar Allan Poe, who wrote numerous short stories and poems reinterpreting Gothic tropes. His story "The Fall of the House of Usher" (1839) revisits classic Gothic tropes of aristocratic decay, death, and insanity.[59] Poe is now considered the master of the American Gothic.[1] In England, one of the most influential penny dreadfuls is the anonymously authored Varney the Vampire (1847), which introduced the trope of vampires having sharpened teeth.[60] Another notable English author of penny dreadfuls is George W. M. Reynolds, known for The Mysteries of London (1844), Faust (1846), Wagner the Wehr-wolf (1847), and The Necromancer (1857).[61] Elizabeth Gaskell's tales "The Doom of the Griffiths" (1858), "Lois the Witch", and "The Grey Woman" all employ one of the most common themes of Gothic fiction: the power of ancestral sins to curse future generations, or the fear that they will. M. R. James, an English medievalist whose stories are still popular today, is known as the originator of the "antiquarian ghost story." In Spain, Gustavo Adolfo Bécquer stood out with his romantic poems and short tales, some depicting supernatural events. Today some consider him the most-read Spanish writer after Miguel de Cervantes.[62]  In addition to these short Gothic fictions, some novels drew on the Gothic. Emily Brontë's Wuthering Heights (1847) transports the Gothic to the forbidding Yorkshire Moors and features ghostly apparitions and a Byronic hero in the person of the demonic Heathcliff. The Brontës' fictions were cited by feminist critic Ellen Moers as prime examples of Female Gothic, exploring woman's entrapment within domestic space and subjection to patriarchal authority and the transgressive and dangerous attempts to subvert and escape such restriction.[63] Emily Brontë's Cathy and Charlotte Brontë's Jane Eyre are examples of female protagonists in such roles.[64] Louisa May Alcott's Gothic potboiler, A Long Fatal Love Chase (written in 1866 but published in 1995), is also an interesting specimen of this subgenre. Charlotte Brontë's Villette also shows the Gothic influence, with its supernatural subplot featuring a ghostly nun, and its view of Roman Catholicism as exotic and heathenistic.[65][66] Nathaniel Hawthorne's novel The House of the Seven Gables, about a family's ancestral home, is colored with suggestions of the supernatural and witchcraft; and in true Gothic fashion, it features the house itself as one of the main characters,  The genre also heavily influenced writers such as Charles Dickens, who read Gothic novels as a teenager and incorporated their gloomy atmosphere and melodrama into his works, shifting them to a more modern period and an urban setting; for example, in Oliver Twist (1837–1838), Bleak House (1852–1853) and Great Expectations (1860–1861). These works juxtapose wealthy, ordered, and affluent civilization with the disorder and barbarity of the poor in the same metropolis. Bleak House, in particular, is credited with introducing urban fog to the novel, which would become a frequent characteristic of urban Gothic literature and film.[67] Miss Havisham from Great Expectations, is one of Dickens' most Gothic characters. The bitter recluse shuts herself away in her gloomy mansion ever since being jilted at the altar on her wedding day.[68] His most explicitly Gothic work is his last novel, The Mystery of Edwin Drood, which he did not live to complete and was published unfinished upon his death in 1870.[69] The mood and themes of the Gothic novel held a particular fascination for the Victorians, with their obsession with mourning rituals, mementos, and mortality in general. Irish Catholics also wrote Gothic fiction in the 19th century. Although some Anglo-Irish dominated and defined the subgenre decades later, they did not own it. Irish Catholic Gothic writers included Gerald Griffin, James Clarence Mangan, and John and Michael Banim. William Carleton was a notable Gothic writer, and converted from Catholicism to Anglicanism.[70] In Switzerland, Jeremias Gotthelf wrote The Black Spider (1842), an allegorical work that uses Gothic themes. The last work from the German writer Theodor Storm, The Rider on the White Horse (1888), also uses Gothic motives and themes.[71] After Gogol, Russian literature saw the rise of Realism, but many authors continued to write stories within Gothic fiction territory. Ivan Sergeyevich Turgenev, one of the most celebrated Realists, wrote Faust (1856), Phantoms (1864), Song of the Triumphant Love (1881), and Clara Milich (1883). Another classic Russian Realist, Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoyevsky, incorporated Gothic elements into many of his works, although none can be seen as purely Gothic.[72] Grigory Petrovich Danilevsky, who wrote historical and early science fiction novels and stories, wrote Mertvec-ubiytsa (Dead Murderer) in 1879. Also, Grigori Alexandrovich Machtet wrote "Zaklyatiy kazak", which may now also be considered Gothic.[73]  The 1880s saw the revival of the Gothic as a powerful literary form allied to fin de siecle, which fictionalized contemporary fears like ethical degeneration and questioned the social structures of the time. Classic works of this Urban Gothic include Robert Louis Stevenson's Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1886), Oscar Wilde's The Picture of Dorian Gray (1891), George du Maurier's Trilby (1894), Richard Marsh's The Beetle (1897), Henry James' The Turn of the Screw (1898), and the stories of Arthur Machen. In Ireland, Gothic fiction tended to be purveyed by the Anglo-Irish Protestant Ascendancy. According to literary critic Terry Eagleton, Charles Maturin, Sheridan Le Fanu, and Bram Stoker form the core of the Irish Gothic subgenre with stories featuring castles set in a barren landscape and a cast of remote aristocrats dominating an atavistic peasantry, which represent an allegorical form the political plight of Catholic Ireland subjected to the Protestant Ascendancy.[74] Le Fanu's use of the gloomy villain, forbidding mansion, and persecuted heroine in Uncle Silas (1864) shows direct influence from Walpole's Otranto and Radcliffe's Udolpho. Le Fanu's short story collection In a Glass Darkly (1872) includes the superlative vampire tale Carmilla, which provided fresh blood for that particular strand of the Gothic and influenced Bram Stoker's vampire novel Dracula (1897). Stoker's book created the most famous Gothic villain ever, Count Dracula, and established Transylvania and Eastern Europe as the locus classicus of the Gothic.[75] Published in the same year as Dracula, Florence Marryat's The Blood of the Vampire is another piece of vampire fiction. The Blood of the Vampire, which, like Carmilla, features a female vampire, is notable for its treatment of vampirism as both racial and medicalized. The vampire, Harriet Brandt, is also a psychic vampire, killing unintentionally.[76] In the United States, notable late 19th-century writers in the Gothic tradition were Ambrose Bierce, Robert W. Chambers, and Edith Wharton. Bierce's short stories were in the horrific and pessimistic tradition of Poe. Chambers indulged in the decadent style of Wilde and Machen, even including a character named Wilde in his The King in Yellow (1895).[77] Wharton published some notable Gothic ghost stories. Some works of the Canadian writer Gilbert Parker also fall into the genre, including the stories in The Lane that had No Turning (1900).[78]  The serialized novel The Phantom of the Opera (1909–1910) by the French writer Gaston Leroux is another well-known example of Gothic fiction from the early 20th century, when many German authors were writing works influenced by Schauerroman, including Hanns Heinz Ewers.[79] Russian GothicUntil the 1990s, Russian Gothic critics did not view Russian Gothic as a genre or label. If used, the word "gothic" was used to describe (mostly early) works of Fyodor Dostoyevsky from the 1880s. Most critics used tags such as "Romanticism" and "fantastique", such as in the 1984 story collection translated into English as Russian 19th-Century Gothic Tales but originally titled Фантастический мир русской романтической повести, literally, "The Fantastic World of Russian Romanticism Short Story/Novella."[80] However, since the mid-1980s, Russian gothic fiction as a genre began to be discussed in books such as The Gothic-Fantastic in Nineteenth-Century Russian Literature, European Gothic: A Spirited Exchange 1760–1960, The Russian Gothic Novel and its British Antecedents and Goticheskiy roman v Rossii (The Gothic Novel in Russia). The first Russian author whose work has been described as gothic fiction is considered to be Nikolay Mikhailovich Karamzin. While many of his works feature gothic elements, the first to belong purely under the gothic fiction label is Ostrov Borngolm (Island of Bornholm) from 1793.[81] Nearly ten years later, Nikolay Ivanovich Gnedich followed suit with his 1803 novel Don Corrado de Gerrera, set in Spain during the reign of Philip II.[82] The term "Gothic" is sometimes also used to describe the ballads of Russian authors such as Vasily Andreyevich Zhukovsky, particularly "Ludmila" (1808) and "Svetlana" (1813), both translations based on Gottfreid August Burger's Gothic German ballad, "Lenore".[83] During the last years of Imperial Russia in the early 20th century, many authors continued to write in the Gothic fiction genre. They include the historian and historical fiction writer Alexander Valentinovich Amfiteatrov and Leonid Nikolaievich Andreyev, who developed psychological characterization; the symbolist Valery Yakovlevich Bryusov, Alexander Grin, Anton Pavlovich Chekhov;[84] and Aleksandr Ivanovich Kuprin.[73] Nobel Prize winner Ivan Alekseyevich Bunin wrote Dry Valley (1912), which is seen as influenced by Gothic literature.[85] In a monograph on the subject, Muireann Maguire writes, "The centrality of the Gothic-fantastic to Russian fiction is almost impossible to exaggerate, and certainly exceptional in the context of world literature."[86] Twentienth-century Gothic fiction Gothic fiction and Modernism influenced each other. This is often evident in detective fiction, horror fiction, and science fiction, but the influence of the Gothic can also be seen in the high literary Modernism of the 20th century. Oscar Wilde's The Picture of Dorian Gray (1890) initiated a re-working of older literary forms and myths that became common in the work of W. B. Yeats, T. S. Eliot, James Joyce, Virginia Woolf, Shirley Jackson, and Angela Carter, among others.[88] In Joyce's Ulysses (1922), the living are transformed into ghosts, which points to an Ireland in stasis at the time and a history of cyclical trauma from the Great Famine in the 1840s through to the current moment in the text.[89] The way Ulysses uses Gothic tropes such as ghosts and hauntings while removing the supernatural elements of 19th-century Gothic fiction indicates a general form of modernist Gothic writing in the first half of the 20th century.  In America, pulp magazines such as Weird Tales reprinted classic Gothic horror tales from the previous century by authors like Poe, Arthur Conan Doyle, and Edward Bulwer-Lytton, and printed new stories by modern authors featuring both traditional and new horrors.[90] The most significant of these was H. P. Lovecraft, who also wrote a conspectus of the Gothic and supernatural horror tradition in his Supernatural Horror in Literature (1936), and developed a Mythos that would influence Gothic and contemporary horror well into the 21st century. Lovecraft's protégé, Robert Bloch, contributed to Weird Tales and penned Psycho (1959), which drew on the classic interests of the genre. From these, the Gothic genre per se gave way to modern horror fiction, regarded by some literary critics as a branch of the Gothic,[91] although others use the term to cover the entire genre. The Romantic strand of Gothic was taken up in Daphne du Maurier's Rebecca (1938), which is seen by some to have been influenced by Charlotte Brontë's Jane Eyre.[92] Other books by du Maurier, such as Jamaica Inn (1936), also display Gothic tendencies. Du Maurier's work inspired a substantial body of "female Gothics," concerning heroines alternately swooning over or terrified by scowling Byronic men in possession of acres of prime real estate and the appertaining droit du seigneur. Southern GothicThe genre also influenced American writing, creating a Southern Gothic genre that combines some Gothic sensibilities, such as the grotesque, with the setting and style of the Southern United States. Examples include Erskine Caldwell, William Faulkner, Carson McCullers, John Kennedy Toole, Manly Wade Wellman, Eudora Welty, V. C. Andrews, Tennessee Williams, Truman Capote, Flannery O'Connor, Davis Grubb, Anne Rice, Harper Lee, and Cormac McCarthy.[93] New Gothic romancesMass-produced Gothic romances became popular in the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s with authors such as Phyllis A. Whitney, Joan Aiken, Dorothy Eden, Victoria Holt, Barbara Michaels, Mary Stewart, Alicen White, and Jill Tattersall. Many featured covers show a terror-stricken woman in diaphanous attire in front of a gloomy castle, often with a single-lit window. Many were published under the Paperback Library Gothic imprint and marketed to female readers. While the authors were mostly women, some men wrote Gothic romances under female pseudonyms: the prolific Clarissa Ross and Marilyn Ross were pseudonyms of the male Dan Ross; Frank Belknap Long published Gothics under his wife's name, Lyda Belknap Long; the British writer Peter O'Donnell wrote under the pseudonym Madeleine Brent. After the gothic romance boom faded away in the early 1990s, very few publishers embraced the term for mass market romance paperbacks apart from imprints like Love Spell, which was discontinued in 2010.[94] However, in recent years the term "Gothic Romance" is being used to describe both old and new works of Gothic fiction.[95] Contemporary GothicGothic fiction continues to be extensively practised by contemporary authors. Many modern writers of horror or other types of fiction exhibit considerable Gothic sensibilities – examples include Anne Rice, Susan Hill, Ray Russell, Billy Martin, Silvia Moreno-Garcia, Carmen Maria Machado, Neil Gaiman, and Stephen King.[96][97] Thomas M. Disch's novel The Priest (1994) was subtitled A Gothic Romance and partly modeled on Matthew Lewis' The Monk.[98][99][100] Many writers such as Billy Martin, Stephen King, Brett Easton Ellis, and Clive Barker have focused on the body's surface and blood's visuality.[101] England's Rhiannon Ward is among the recent writers of Gothic fiction. Catriona Ward won a British Fantasy Award for Best Horror Novel for her gothic novel Rawblood in 2016. Contemporary American writers in the tradition include Joyce Carol Oates with such novels as Bellefleur and A Bloodsmoor Romance, Toni Morrison with her radical novel Beloved, about a slave-woman whose murdered baby haunts her, Raymond Kennedy with his novel Lulu Incognito,[102] Donna Tartt with her postmodern gothic horror novel The Secret History,[103] Ursula Vernon with her Edgar Allan Poe-inspired novel What Moves the Dead, Danielle Trussoni with her "gothic extravaganza" The Ancestor,[104] and filmmaker Anna Biller with Bluebeard's Castle, a throwback to 18th-century Gothic novels and 1960s dime-store romances.[105] British writers who have continued in the Gothic tradition include Sarah Waters with her haunted house novel The Little Stranger,[106] Diane Setterfield with her quintessentially Gothic novels The Thirteenth Tale[107] and Once Upon a River, Helen Oyeyemi with her experimental novel White is for Witching,[108] Sarah Perry with her novels Melmoth and The Essex Serpent,[109] and Laura Purcell with her historical novels The Silent Companions and The Shape of Darkness.[110] Several Gothic traditions have also developed in New Zealand (with the subgenre referred to as New Zealand Gothic or Maori Gothic)[111] and Australia (known as Australian Gothic). These explore everything from the multicultural natures of the two countries[112] to their natural geography.[113] Novels in the Australian Gothic tradition include Kate Grenville's The Secret River and the works of Kim Scott.[114] An even smaller genre is Tasmanian Gothic, set exclusively on the island, with prominent examples including Gould's Book of Fish by Richard Flanagan and The Roving Party by Rohan Wilson.[115][116][117][118] Another Australian author, Kate Morton, has penned several homages to classic gothic fiction, among them The Distant Hours and The House at Riverton.[119] Southern Ontario Gothic applies a similar sensibility to a Canadian cultural context. Robertson Davies, Alice Munro, Barbara Gowdy, Timothy Findley, and Margaret Atwood have all produced notable exemplars of this form. Another writer in the tradition was Henry Farrell, best known for his 1960 Hollywood horror novel What Ever Happened To Baby Jane? Farrell's novels spawned a subgenre of "Grande Dame Guignol" in the cinema, represented by such films as the 1962 film based on Farrell's novel, which starred Bette Davis versus Joan Crawford; this subgenre of films was dubbed the "psycho-biddy" genre. Outside the English-speaking world, Latin American Gothic literature has been gaining momentum since the first decades of the 21st century. Some of the main authors whose style has been described as Gothic are María Fernanda Ampuero, Mariana Enríquez, Fernanda Melchor, Mónica Ojeda, Giovanna Rivero, and Samanta Schweblin. The many Gothic subgenres include a new "environmental Gothic" or "ecoGothic".[120][121][122] It is an ecologically aware Gothic engaged in "dark nature" and "ecophobia."[123] Writers and critics of the ecoGothic suggest that the Gothic genre is uniquely positioned to speak to anxieties about climate change and the planet's ecological future.[124] Among the bestselling books of the 21st century, the YA novel Twilight by Stephenie Meyer is now increasingly identified as a Gothic novel, as is Carlos Ruiz Zafón's 2001 novel The Shadow of the Wind.[125] Other mediaLiterary Gothic themes have been translated into other media. There was a notable revival in 20th-century Gothic horror cinema, such as the classic Universal Monsters films of the 1930s, Hammer Horror films, and Roger Corman's Poe cycle.[126] In Hindi cinema, the Gothic tradition was combined with aspects of Indian culture, particularly reincarnation, for an "Indian Gothic" genre, beginning with Mahal (1949) and Madhumati (1958).[127] The 1960s Gothic television series Dark Shadows borrowed liberally from Gothic traditions, with elements like haunted mansions, vampires, witches, doomed romances, werewolves, obsession, and madness. The early 1970s saw a Gothic Romance comic book mini-trend with such titles as DC Comics' The Dark Mansion of Forbidden Love and The Sinister House of Secret Love, Charlton Comics' Haunted Love, Curtis Magazines' Gothic Tales of Love, and Atlas/Seaboard Comics' one-shot magazine Gothic Romances.  Twentieth-century rock music also had its Gothic side. Black Sabbath's 1970 debut album created a dark sound different from other bands at the time and has been called the first-ever "goth-rock" record.[128] However, the first recorded use of "gothic" to describe a style of music was for The Doors. Critic John Stickney used the term "gothic rock" to describe the music of The Doors in October 1967 in a review published in The Williams Record.[129] Other forerunners who initially shaped the aesthetics and musical conventions of gothic rock include Marc Bolan,[130] the Velvet Underground, David Bowie, Brian Eno, and Iggy Pop.[131] Critic Simon Reynolds retrospectively described Kate Bush's 1978 song "Wuthering Heights"—with its lyrics inspired by Emily Brontë's 1847 novel Wuthering Heights featuring Cathy as a ghost and the tortured anti-hero Heathcliff—as "Gothic romance distilled into four-and-a-half minutes of gaseous rhapsody".[132] Gothic rock as a music genre emerged in late 1970s England, with Bauhaus's debut single, "Bela Lugosi's Dead", released in late 1979, retrospectively considered to be the beginning of the genre.[133] This was followed by the album Unknown Pleasures by Joy Division a year later, and in the early 1980s, post-punk bands such as the Cure and Siouxsie and the Banshees included more gothic characteristics in their music.[134] Tracing the genre from its 18th-century literary roots through its flourishing as a music subculture from the late 1970s onward, the Cure's Lol Tolhurst wrote, "Goth is about being in love with the melancholy beauty of existence".[135][136] Themes from Gothic writers such as H. P. Lovecraft were used among Gothic rock and heavy metal bands, especially in black metal, thrash metal (Metallica's The Call of Ktulu), death metal, and gothic metal. For example, in his compositions, heavy metal musician King Diamond delights in telling stories full of horror, theatricality, Satanism, and anti-Catholicism.[137] In role-playing games (RPG), the pioneering 1983 Dungeons & Dragons adventure Ravenloft instructs the players to defeat the vampire Strahd von Zarovich, who pines for his dead lover. It has been acclaimed as one of the best role-playing adventures ever and even inspired an entire fictional world of the same name. The World of Darkness is a gothic-punk RPG line set in the real world, with the added element of supernatural creatures such as werewolves and vampires. In addition to its flagship title Vampire: The Masquerade, the game line features a number of spin-off RPGs such as Werewolf: The Apocalypse, Mage: The Ascension, Wraith: The Oblivion, Hunter: The Reckoning, and Changeling: The Dreaming, allowing for a wide range of characters in the gothic-punk setting. My Life with Master uses Gothic horror conventions as a metaphor for abusive relationships, placing the players in the shoes of minions of a tyrannical, larger-than-life Master.[138] Various video games feature Gothic horror themes and plots. The Castlevania series typically involves a hero of the Belmont lineage exploring a dark, old castle, fighting vampires, werewolves, Frankenstein's Creature, and other Gothic monster staples, culminating in a battle against Dracula himself. Others, such as Ghosts 'n Goblins, feature a camper parody of Gothic fiction. 2017's Resident Evil 7: Biohazard, a Southern Gothic reboot to the survival horror video game involves an everyman and his wife trapped in a derelict plantation and mansion owned by a family with sinister and hideous secrets and must face terrifying visions of a ghostly mutant in the shape of a little girl. This was followed by 2021's Resident Evil Village, a Gothic horror sequel focusing on an action hero searching for his kidnapped daughter in a mysterious Eastern European village under the control of a bizarre religious cult inhabited by werewolves, vampires, ghosts, shapeshifters, and other monsters. The Devil May Cry series stands as an equally parodic and self-serious franchise, following the escapades, stunts and mishaps of series protagonist Dante as he explores dingy demonic castles, ancient occult monuments and ruined urban landscapes on his quest to avenge his mother and brother. Gothic literary themes appear all throughout the story, such as how the past physically creeps into the ambiguously modern setting, recurrent imagery of doubles (notably regarding Dante and his twin brother), and the persisting melodramas associated with Dante's father's fame, absence, and demonic heritage. Beginning with Devil May Cry 3: Dante's Awakening, Female Gothic elements enter the series as deuteragonist Lady works through her own revenge plot against her murderous father, with the oppressive and consistent emotional and physical abuse instigated by a patriarchal figure serving as a heavy, understated counterweight to the extravagance of the rest of the story. Finally, Bloodborne takes place in the decaying Gothic city of Yharnam, where the player must face werewolves, shambling mutants, vampires, witches, and numerous other Gothic staple creatures. However, the game takes a marked turn midway shifting from gothic to Lovecraftian horror. Popular tabletop card game Magic: The Gathering, known for its parallel universe consisting of "planes," features the plane known as Innistrad. Its general aesthetic is based on northeast European Gothic horror. Innistard's common residents include cultists, ghosts, vampires, werewolves, and zombies. Film director Tim Burton, whose influences include Universal Monsters movies such as Frankenstein, Hammer Horror films starring Christopher Lee and the horror films of Vincent Price, is known for creating a gothic aesthetic in his films.[139] Modern Gothic horror films include Sleepy Hollow,[140] Interview with the Vampire,[141] Underworld,[142] The Wolfman,[143] From Hell,[144] Dorian Gray,[145] Let the Right One In,[146] The Woman in Black,[147] Crimson Peak,[148] The Little Stranger,[149] and The Love Witch.[150] The TV series Penny Dreadful (2014–2016) brings many classic Gothic characters together in a psychological thriller set in the dark corners of Victorian London.[151] The Oscar-winning Korean film Parasite has also been called Gothic – specifically, Revolutionary Gothic.[152] Recently, the Netflix original The Haunting of Hill House and its successor The Haunting of Bly Manor have integrated classic Gothic conventions into modern psychological horror.[153] ScholarshipEducators in literary, cultural, and architectural studies appreciate the Gothic as an area that facilitates investigation of the beginnings of scientific certainty. As Carol Senf has stated, "the Gothic was... a counterbalance produced by writers and thinkers who felt limited by such a confident worldview and recognized that the power of the past, the irrational, and the violent continue to sway in the world."[154] As such, the Gothic helps students better understand their doubts about the self-assurance of today's scientists. Scotland is the location of what was probably the world's first postgraduate program to consider the genre exclusively: the MLitt in the Gothic Imagination at the University of Stirling, first recruited in 1996.[155] See also

Notes

References

External links

|