|

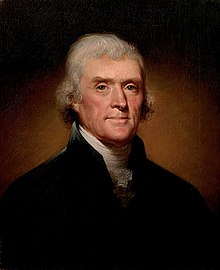

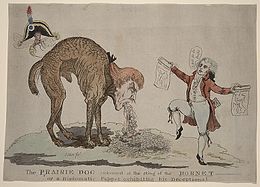

History of U.S. foreign policy, 1801–1829 The history of U.S. foreign policy from 1801 to 1829 concerns the foreign policy of the United States during the presidential administrations of Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, James Monroe, and John Quincy Adams. International affairs in the first half of this period were dominated by the Napoleonic Wars, which the United States became involved with in various ways, including the War of 1812. The period saw the U.S. double in size, gaining control of Florida and lands between the Mississippi River and the Rocky Mountains. The period began with the First inauguration of Thomas Jefferson in 1801. The First inauguration of Andrew Jackson in 1829 marked the start of the next period in U.S. foreign policy. Upon taking office, President Jefferson dispatched envoys to the French First Republic to purchase the city of New Orleans, which held a strategic position on the Mississippi River. French Emperor Napoleon instead offered to sell the entire territory of Louisiana; the Jefferson administration accepted the offer, and the subsequent Louisiana Purchase doubled the size of the U.S. During Jefferson's second term, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland escalated attacks against American shipping as part of a blockade against France. These attacks continued under President Madison, and in 1812 the U.S. declared war against Britain, beginning the War of 1812. Defying Madison's hopes that the war would end with the quick capture of Canada under British rule, the War of 1812 continued inconclusively until 1815. The Treaty of Ghent provided for a return to status quo ante bellum borders, and the final defeat of Napoleon later in 1815 ended the issue of British and French attacks on American shipping. Though the war with Britain was inconclusive, the U.S. defeated Native American allies of Britain at the Battle of the Thames and the Battle of Horseshoe Bend, ensuring U.S. control of the Old Northwest and the Old Southwest. In the aftermath of the war, the U.S. and Britain signed two treaties that eased tensions, settled border disputes, demilitarized the Great Lakes, and provided for the joint occupation of Oregon Country. A separate treaty with the Russian Empire established the southern border of Russian America and opened Russian ports to U.S. trade. In 1819, the United States and the Kingdom of Spain agreed to the Adams–Onís Treaty, through which Spain transferred control of Florida to the United States. Numerous Latin American countries gained independence from Spain during Monroe's presidency. In 1823, he promulgated the Monroe Doctrine, under which the U.S. pledged to oppose all future efforts to colonize the Western Hemisphere. LeadershipJefferson administration, 1801–1809Thomas Jefferson took office in 1801 after defeating incumbent President John Adams in the 1800 presidential election. By July 1801, Jefferson had assembled his cabinet, which consisted of Secretary of State James Madison, Secretary of the Treasury Albert Gallatin, Secretary of War Henry Dearborn, Attorney General Levi Lincoln Sr., and Secretary of the Navy Robert Smith. Jefferson sought to make collective decisions with his cabinet, and each member's opinion was elicited before Jefferson made major decisions.[1] Gallatin and Madison were particularly influential within Jefferson's cabinet; they held the two most important cabinet positions and served as Jefferson's key lieutenants.[2] Madison administration, 1809–1817Jefferson's preferred successor, James Madison, took office in 1809 after winning the 1808 presidential election.[3] Upon his inauguration in 1809, Madison immediately faced opposition to his planned nomination of Albert Gallatin as Secretary of State; Madison chose not to fight Congress for the nomination but kept Gallatin in the Treasury Department. The talented Swiss-born Gallatin was Madison's primary advisor, confidant, and policy planner.[4] Madison appointed Secretary of State Robert Smith only at the behest of Smith's brother, the powerful Senator Samuel Smith. With a cabinet full of those he distrusted, Madison rarely called cabinet meetings and instead frequently consulted with Gallatin alone.[5] After feuding with Gallatin, Smith was dismissed in 1811 in favor of James Monroe, and Monroe became a major influence in the Madison administration.[6] Monroe administration, 1817–1825James Monroe became president in 1817 after his victory in the 1816 presidential election. Monroe appointed a geographically-balanced cabinet, through which he led the executive branch.[7] Monroe retained many of Madison's appointments, but, recognizing Northern discontent at the continuation of the Virginia dynasty, Monroe chose John Quincy Adams of Massachusetts to fill the prestigious post of Secretary of State.[8] Adams administration, 1825–1829John Quincy Adams took office in 1825 after defeating Andrew Jackson, William H. Crawford, and Henry Clay in the 1824 presidential election. As no one candidate won a majority of the electoral vote in the 1824 election, the election was decided by the House of Representatives in a contingent election that Adams won with the support of Clay.[9] Like Monroe, Adams sought a geographically-balanced cabinet that would represent the various party factions, and he asked the members of the Monroe cabinet to remain in place for his own administration.[10] Adams chose Henry Clay as Secretary of State, angering those who believed that Clay had offered his support in the 1824 election for the most prestigious position in the cabinet.[11] Adams presided over a harmonious and productive cabinet. He met with the cabinet as a group on a weekly basis to discuss major issues of policy, and he gave individual cabinet members a great deal of discretion in carrying out their duties.[12] Louisiana Purchase Jefferson believed that western expansion played an important role in furthering his vision of a republic of yeoman farmers. By the time Jefferson took office, Americans had settled as far west as the Mississippi River, though vast pockets of land remained vacant or inhabited only by Native Americans.[13] Many in the United States, particularly those in the west, favored further territorial expansion, and especially hoped to annex the Spanish province of Louisiana.[14] Given Spain's sparse presence in Louisiana, Jefferson believed that it was just a matter of time until Louisiana fell to either Britain or the United States.[15] U.S. expansionary hopes were temporarily dashed when Napoleon convinced Spain to transfer the province to France in the 1801 Treaty of Aranjuez.[14] Though French pressure played a role in the conclusion of the treaty, the Spanish also believed that French control of Louisiana would help protect New Spain from American expansion.[15] Napoleon's dreams of a re-established French colonial empire in North America threatened to reignite the tensions of the recently concluded Quasi-War.[14] He initially planned to re-establish a French empire in the Americas centered around New Orleans and Saint-Domingue, a sugar-producing Caribbean island in the midst of a slave revolution. One army was sent to Saint-Domingue, and a second army began preparing to travel to New Orleans. After French forces in Saint-Domingue were defeated by the rebels, Napoleon gave up on his plans for an empire in the Western Hemisphere.[16] In early 1803, Jefferson dispatched James Monroe to France to join ambassador Robert Livingston in purchasing New Orleans, East Florida, and West Florida from France.[17] To the surprise of the American delegation, Napoleon offered to sell the entire territory of Louisiana for $15 million.[18] The Americans also pressed for the acquisition of the Floridas, but under the terms of the Treaty of Aranjuez, Spain retained control of both of those territories. On April 30, the two delegations agreed to the terms of the Louisiana Purchase, and Napoleon gave his approval the following day.[19] After Secretary of State James Madison gave his assurances that the purchase was well within even the strictest interpretation of the Constitution, the Senate quickly ratified the treaty, and the House immediately authorized funding.[20] The purchase, concluded in December 1803, marked the end of French ambitions in North America and ensured American control of the Mississippi River.[21] The Louisiana Purchase nearly doubled the size of the United States, and Treasury Secretary Gallatin was forced to borrow from foreign banks to finance the payment to France.[22] Though the Louisiana Purchase was widely popular, some Federalists criticized it; Congressman Fisher Ames argued that "we are to spend money of which he have too little for land of which we already have too much."[23] Burr conspiracyAfter being dropped from Jefferson's 1804 Republican ticket, Burr was defeated for governor of New York in an April 1804 election. On July 11, 1804, Burr killed his political enemy Alexander Hamilton in a duel. Burr was indicted for murder in New York and New Jersey causing him to flee to Georgia. The British ambassador reported that Burr wanted to "effect a separation of the western part of the United States [at the Appalachian Mountains]". Jefferson believed that to be so by November 1806, because Burr had been rumored to be variously plotting with some western states to secede for an independent empire, or to raise a filibuster to conquer Mexico. At the very least, there were reports of Burr's recruiting men, stocking arms, and building boats. New Orleans seemed especially vulnerable, but at some point, the American general there, James Wilkinson, a double agent for the Spanish, decided to turn on Burr. Jefferson issued a proclamation warning that there were U.S. citizens illegally plotting to take over Spanish holdings. Though Burr was nationally discredited, Jefferson feared for the very Union. By March 1807, Burr was arrested and placed on trial for treason; he was acquitted and went into exile in Europe.[24] War of 1812Embargo ActAmerican trade boomed after the outbreak of the French Revolutionary Wars in the early 1790s, in large part because American shipping was allowed to act as neutral carriers with European powers.[25] Though the British sought to restrict trade with the French, they had largely tolerated U.S. trade with mainland France and French colonies after the signing of the Jay Treaty in 1794.[26] Jefferson favored a policy of neutrality in the European wars, and was strongly committed the principle of freedom of navigation for neutral vessels, including American ships.[27] Early in his tenure, Jefferson was able to maintain cordial relations with both France and Britain, but relations with Britain deteriorated after 1805.[28] Needing sailors, the British Royal Navy seized hundreds of American ships and impressed 6,000 alleged British deserters from them, angering Americans.[29] The British began to enforce a blockade of Europe, ending their policy of tolerance towards American shipping. Though the British returned many seized American goods that had not been intended for French ports, the British blockade badly affected American commerce and provoked immense anger throughout the nation. Aside from commercial concerns, Americans were outraged by what they saw an attack on national honor. In response to the attacks, Jefferson recommended an expansion of the navy, and Congress passed the Non-importation Act, which restricted many, but not all, British imports.[30] To restore peaceful relations with Britain, Monroe negotiated the Monroe–Pinkney Treaty, which would have represented an extension of the Jay Treaty.[31] Jefferson had never favored the Jay Treaty, which had prevented the United States from implementing economic sanctions on Britain, and he rejected the Monroe–Pinkney Treaty. Tensions with Britain heightened due to the Chesapeake–Leopard affair, a June 1807 naval confrontation between USS Chesapeake and HMS Leopard that resulted in four British deserters from Chesapeake being impressed. Beginning with Napoleon's December 1807 Milan Decree, the French began to seize ships trading with the British, leaving American shipping vulnerable to seizures by both of the major naval powers.[32] In response to seizures on American shipping, Congress passed the Embargo Act in 1807, which was designed to force Britain and France into respecting U.S. neutrality by cutting off all American shipping to Britain or France. Almost immediately the Americans began to turn to smuggling in order to ship goods to Europe.[33] Defying his own limited government principles, Jefferson used the military to enforce the embargo. Imports and exports fell immensely, and the embargo proved to be especially unpopular in New England.[34] Most historians consider Jefferson's embargo to have been ineffective and harmful to American interests.[35] Even the top officials of the Jefferson administration viewed the embargo as a flawed policy, but they saw it as preferable to war.[36] Appleby describes the strategy as Jefferson's "least effective policy", and Joseph Ellis calls it "an unadulterated calamity".[37] Others, however, portray it as an innovative, nonviolent measure which aided France in its war with Britain while preserving American neutrality.[38] Prelude to warIn early 1809, Congress passed the Non-Intercourse Act, which opened trade with foreign powers other than France and Britain.[39] Aside from U.S. trade with France, the central dispute between Britain and the United States was the impressment of sailors on American ships by the Royal Navy. During the Napoleonic Wars, numerous British subjects were impressed into the Royal Navy, and many of them deserted to U.S. merchant ships. Unable to tolerate this loss of manpower, the Royal Navy seized several U.S. ships and impressed deserters, with some American sailors being mistaken for deserters also being impressed as well. Though Americans were outraged by this impressment, they also refused to take steps to limit it, such as refusing to hire British deserters. For economic reasons, American merchants preferred impressment to giving up their right to hire British deserters.[40] Although initially promising, President Madison's diplomatic efforts to get the British to withdraw the Orders in Council were rejected by Foreign Secretary George Canning in April 1809.[41] In August 1809, diplomatic relations with Britain deteriorated as minister David Erskine was withdrawn and replaced by "hatchet man" Francis James Jackson.[42] Madison resisted calls for war, as he was ideologically opposed to the debt and taxes necessary for a war effort.[43] British historian Paul Langford sees the removal in 1809 of Erskine as a major blunder, because Erskine:

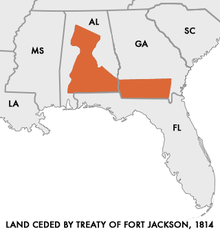

Powell 1873. After Jackson accused Madison of duplicity with Erskine, Madison had Jackson barred from the State Department and sent packing to Boston.[45] In early 1810, Madison began asking Congress for more appropriations to increase the army and navy in preparation for war with Britain.[46] Congress also passed an act known as Macon's Bill Number 2, which reopened trade with France and Britain, but promised to reimpose the embargo on one country if the other country agreed to end its attacks on American shipping. Madison, who wished to simply continue the embargo, opposed the law, but he jumped at the chance to use the law's provision enabling a re-imposition of the embargo on one power.[47] Seeking to split the Americans and British, Napoleon offered to end French attacks on American shipping so long as the United States punished any countries that did not similarly end restrictions on trade.[48] Madison accepted Napoleon's proposal in the hope that it would convince the British to revoke the Orders-in-Council, but the British refused to change their policies.[49] Despite assurances to the contrary, the French also continued to attack American shipping.[50] As the seizures of American shipping continued, both Madison and the broader American public were ready for war with Britain.[51] Some observers believed that the United States might fight a three-way war with both Britain and France, but Democratic-Republicans, including Madison, considered Britain to be far more culpable for the seizures.[52] Many Americans called for a "second war of independence" to restore honor and stature to the new nation, and an angry public elected a "war hawk" Congress, led by Henry Clay and John C. Calhoun.[53] With Britain in the midst of the Napoleonic Wars, many Americans, Madison included, believed that the United States could easily capture Canada, at which point the U.S. could use Canada as a bargaining chip for all other disputes or simply retain control of it.[54] On June 1, 1812, Madison asked Congress for a declaration of war.[55] The declaration was passed along sectional and party lines, with intense opposition from the Federalists and the Northeast, where the economy had suffered during Jefferson's trade embargo.[56][57] Madison hurriedly called on Congress to put the country "into an armor and an attitude demanded by the crisis," specifically recommending enlarging the army, preparing the militia, finishing the military academy, stockpiling munitions, and expanding the navy.[58] Madison faced formidable obstacles—a divided cabinet, a factious party, a recalcitrant Congress, obstructionist governors, and incompetent generals, together with militia who refused to fight outside their states. The most serious problem facing the war effort was lack of unified popular support. There were serious threats of disunion from New England, which engaged in extensive smuggling with Canada and refused to provide financial support or soldiers.[59] Events in Europe also went against the United States. Shortly after the United States declared war, Napoleon launched an invasion of Russia, and the failure of that campaign turned the tide against France and towards Britain and her allies.[60] In the years prior to the war, Jefferson and Madison had reduced the size of the military, closed the Bank of the U.S., and lowered taxes. These decisions added to the challenges facing the United States, as by the time the war began, Madison's military force consisted mostly of poorly trained militia members.[61]  Military actionMadison hoped that the war would end in a couple months after the capture of Canada, but his hopes were quickly dashed.[54] Madison had believed the state militias would rally to the flag and invade Canada, but the governors in the Northeast failed to cooperate. Their militias either sat out the war or refused to leave their respective states for action. The senior command at the War Department and in the field proved incompetent or cowardly—the general at Detroit surrendered to a smaller British force without firing a shot. Gallatin discovered the war was almost impossible to fund, since the national bank had been closed, major financiers in the New England refused to help, and government revenue depended largely on tariffs.[62][63] Though the Democratic-Republican Congress was willing to go against party principle to authorize an expanded military, they refused to levy direct taxes until June 1813.[64] Lacking adequate revenue, and with its request for loans refused by New England bankers, the Madison administration relied heavily on high-interest loans furnished by bankers based in New York City and Philadelphia.[65] The American campaign in Canada, led by Henry Dearborn, ended with defeat at the Battle of Stoney Creek.[66] Meanwhile, the British armed American Indians, most notably several tribes allied with the Shawnee chief, Tecumseh, in an attempt to threaten American positions in the Northwest.[67] After the disastrous start to the War of 1812, Madison accepted a Russian invitation to arbitrate the war and sent Gallatin, John Quincy Adams, and James Bayard to Europe in hopes of quickly ending the war.[54] While Madison worked to end the war, the U.S. experienced some military success, particularly at sea. The United States had built up one of the largest merchant fleets in the world, though it had been partially dismantled under Jefferson and Madison. Madison authorized many of these ships to become privateers in the war, and they captured 1,800 British ships.[68] As part of the war effort, an American naval shipyard was built up at Sackets Harbor, New York, where thousands of men produced twelve warships and had another nearly ready by the end of the war.[69] The U.S. naval squadron on Lake Erie successfully defended itself and captured its opponents, crippling the supply and reinforcement of British forces in the western theater of the war.[70] In the aftermath of the Battle of Lake Erie, General William Henry Harrison defeated the forces of the British and of Tecumseh's Confederacy at the Battle of the Thames. The death of Tecumseh in that battle represented the permanent end of armed Native American resistance to U.S. colonization in the Old Northwest.[67] In March 1814, General Andrew Jackson broke the resistance of the British-allied Muscogee in the Old Southwest with his victory at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend.[71] Despite those successes, the British continued to repel American attempts to invade Canada, and a British force captured Fort Niagara and burned the American city of Buffalo in late 1813.[72] In early 1814, the British agreed to begin peace negotiations in the town of Ghent, and the British pushed for the establishment of an Indian barrier state in the Old Northwest as part of any peace agreement.[73]  After Napoleon's abdication following the March 1814 Battle of Paris, the British began to shift soldiers to North America.[74] Under General George Izard and General Jacob Brown, the U.S. launched another invasion of Canada in mid-1814. Despite an American victory at the Battle of Chippawa, the invasion stalled once again.[75] Meanwhile, the British increased the size and intensity of their raids against the Atlantic coast.[76] General William H. Winder attempted to bring together a concentrated force to guard against a potential attack on Washington or Baltimore, but his orders were countermanded by Secretary of War Armstrong.[77] The British landed a large force off the Chesapeake Bay in August 1814, and the British army approached Washington on August 24.[78] An American force was routed at the Battle of Bladensburg, and British forces set fire to the federal buildings of Washington.[79] Dolley Madison rescued White House valuables and documents shortly before the British burned the White House.[80] The British army next moved on Baltimore, but the British called off the raid after the U.S. repelled a naval attack on Fort McHenry. Madison returned to Washington before the end of August, and the main British force departed from the region in September.[81] The British attempted to launch an invasion from Canada, but the U.S. victory at the September 1814 Battle of Plattsburgh ended British hopes of conquering New York.[82] Anticipating that the British would attack the city of New Orleans next, newly-installed Secretary of War James Monroe ordered General Jackson to prepare a defense of the city.[83] Meanwhile, the British public began to turn against the war in North America, and British leaders began to look for a quick exit from the conflict.[84] On January 8, 1815, Jackson's force defeated the British at the Battle of New Orleans.[85] Just over a month later, Madison learned that his negotiators had reached the Treaty of Ghent, ending the war without major concessions by either side. Additionally, both sides agreed to establish commissions to settle Anglo-American boundary disputes. Madison quickly sent the Treaty of Ghent to the Senate, and the Senate ratified the treaty on February 16, 1815.[86] To most Americans, the quick succession of events at the end of the war, including the burning of the capital, the Battle of New Orleans, and the Treaty of Ghent, appeared as though American valor at New Orleans had forced the British to end the war. This view, while inaccurate, strongly contributed to the post-war euphoria that persisted for a decade. It also helps explain the significance of the war, even if it was strategically inconclusive. Madison's reputation as president improved and Americans finally believed the United States had established itself as a world power.[87] Napoleon's defeat at the June 1815 Battle of Waterloo brought a permanent end to the Napoleonic Wars.[88] Aftermath After his victory at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend, Jackson forced the defeated Muscogee to sign the Treaty of Fort Jackson, which forced the Muscogee and the Cherokee (who had been allied with Jackson) to give up control of 22 million acres of land in Alabama and Georgia. Madison initially agreed to restore these lands in the Treaty of Ghent, but Madison backed down in the face of Jackson's resistance. The British largely abandoned their Native allies, and the U.S. consolidated control of its southwest and northwest frontiers.[89] Near the beginning of Monroe's first term, the administration negotiated two important accords with Great Britain that resolved border disputes held over from the War of 1812.[90] The Rush-Bagot Treaty, signed in April 1817, regulated naval armaments on the Great Lakes and Lake Champlain, demilitarizing the border between the U.S. and British North America.[91] The Treaty of 1818, signed in October 1818, fixed the present Canada–United States border from Minnesota to the Rocky Mountains at the 49th parallel.[90] Britain ceded all of Rupert's Land south of the 49th parallel and east of the Continental Divide, including all of the Red River Colony south of that latitude, while the U.S. ceded the northernmost edge of the Missouri Territory above the 49th parallel. The treaty also established a joint U.S.–British occupation of Oregon Country for the next ten years.[90] Together, the Rush-Bagot Treaty and the Treaty of 1818 marked an important turning point in Anglo–American and American–Canadian relations, although they did not solve all outstanding issues.[92] The easing of tensions contributed to expanded trade, particularly cotton, and played a role in Britain's decision to refrain from becoming involved in the First Seminole War.[93] As president, Adams continued to pursue an agreement on territorial disputes with Britain, including the unsettled border between Maine and Canada.[94] Gallatin favored partitioning Oregon Country at the Columbia River, but Adams and Clay were unwilling to concede territory below the 49th parallel north.[95] Barbary WarsFirst Barbary War For decades prior to Jefferson's accession to office, the Barbary Coast pirates of North Africa had been capturing American merchant ships, pillaging valuable cargoes and enslaving crew members, demanding huge ransoms for their release.[96] Before independence, American merchant ships were protected from the Barbary pirates by the naval and diplomatic influence of Great Britain, but that protection came to end after the colonies won their independence.[97] In 1794, in reaction to the attacks, Congress had passed a law to authorize the payment of tribute to the Barbary States. At the same time, Congress passed the Naval Act of 1794, which initiated construction on six frigates that became the foundation of the United States Navy. By the end of the 1790s, the United States had concluded treaties with all of the Barbary States, but weeks before Jefferson took office Tripoli began attacking American merchant ships in an attempt to extract further tribute.[98] Jefferson was reluctant to become involved in any kind of international conflict, but he believed that force would best deter the Barbary States from demanding further tribute. He ordered the U.S. Navy into the Mediterranean Sea to defend against the Barbary Pirates, beginning the First Barbary War. The administration's initial efforts were largely ineffective, and in 1803 the frigate USS Philadelphia was captured by Tripoli. In February 1804, Lieutenant Stephen Decatur led a successful raid on Tripoli's harbor that burned the Philadelphia, making Decatur a national hero.[99] Jefferson and the young American navy forced Tunis and Algiers into breaking their alliance with Tripoli which ultimately moved it out of the war. Jefferson also ordered five separate naval bombardments of Tripoli, which restored peace in the Mediterranean for a while,[100] although Jefferson continued to pay the remaining Barbary States until the end of his presidency.[101] Second Barbary WarDuring the War of 1812, the Barbary States had stepped up attacks on American shipping.[102] These states, which were nominally vassals of the Ottoman Empire but were functionally independent, demanded tribute from countries that traded in the Mediterranean Sea.[103] With the end of the war, the United States could deploy the now-expanded U.S. Navy against the Barbary States. Congress declared war on Algiers in March 1815, beginning the Second Barbary War. Seventeen ships, the largest U.S. fleet that had been assembled up to that point in history, were sent to the Mediterranean Sea. After several defeats, Algiers agreed to sign a treaty, and Tunis and Tripoli also subsequently signed treaties. The Barbary States agreed to release all of their prisoners and to stop demanding tributes.[102] Spanish FloridaWest Florida controversy President Jefferson argued that the Louisiana Purchase had extended as far west as the Rio Grande River, and had included West Florida as far east as the Perdido River. He hoped to use that claim, along with French pressure, to force Spain to sell both West Florida and East Florida. In 1806, he won congressional approval of a $2 million appropriation to obtain the Floridas; eager expansionists also contemplated authorizing the president to acquire Canada, by force if necessary.[105] In this case, unlike that of the Louisiana Territory, the dynamics of European politics worked against Jefferson. Napoleon had played Washington against Madrid to see what he could get, but by 1805 Spain was his ally. Spain had no desire to cede Florida, which was part of its leverage against an expanding United States. Revelations of the bribe which Jefferson offered to France over the matter provoked outrage and weakened Jefferson's hand with regards to Florida.[106] President Madison continued to uphold the U.S. claim to Florida. Spanish control of its New World colonies had weakened due to the ongoing Peninsular War, and Spain exercised little effective control over West Florida and East Florida. Madison was especially concerned about the possibility of the British taking control of the region, which, along with Canada, would give the British Empire control of territories on the northern and southern borders of the United States.[107] However, the United States was reluctant to go to war for the territory when France or Great Britain might intervene.[108] Madison sent William Wykoff into West Florida in the hopes of convincing the settlers of the region to request annexation by the United States. Partly due to Wykoff's prodding, the people of West Florida held the St. Johns Plains Convention in July 1810. Most of those who elected to the convention had been born in the United States, and they largely favored independence from Spain, but they feared that declaring independence would provoke a Spanish military response. In September 1810, after learning that the Spanish governor of West Florida had requested military assistance from Spain, a militia made up of West Floridians and led by Philemon Thomas captured the Spanish fort at Baton Rouge. The leaders of the St. Johns Plains Convention declared the establishment of the Republic of West Florida and requested that Madison send troops to prevent a Spanish reprisal. Acting on his own initiative, the governor of Mississippi Territory. David Holmes, ordered U.S. Army soldiers into West Florida. In what became known as the October Proclamation, Madison announced that the United States had taken control of the Republic of West Florida, assigning it to the Territory of Orleans. Spain retained control of the portion of West Florida east of the Perdido River. Madison also employed George Mathews to stir up a rebellion against Spain in East Florida and the remaining Spanish portions of West Florida, but this effort proved unsuccessful.[107] Seminole WarsSecretary of State John Quincy Adams General Andrew Jackson With a minor military presence in the Floridas, Spain was unable to restrain the Seminole Indians, who routinely conducted cross-border raids on American villages and farms and protected slave refugees from the United States.[109] To stop the Seminole from raiding Georgia settlements and offering havens for runaway slaves, the U.S. Army led increasingly frequent incursions into Spanish territory. In early 1818, Monroe ordered General Andrew Jackson to the Georgia–Florida border to defend against Seminole attacks. Monroe authorized Jackson to attack Seminole encampments in Spanish Florida, but not Spanish settlements themselves.[110] In what became known as the First Seminole War, Jackson crossed over into Spanish territory and attacked the Spanish fort at St. Marks.[111] He also executed two British subjects whom he accused of having incited the Seminoles to raid American settlements.[112] Jackson claimed that the attack on the fort was necessary as the Spanish were providing aid to the Seminoles. After taking the fort St. Marks, Jackson moved on the Spanish position at Pensacola, capturing it in May 1818.[113] In a letter to Jackson, Monroe reprimanded the general for exceeding his orders, but also acknowledged that Jackson may have been justified given the circumstances in the war against the Seminoles.[114] Though he had not authorized Jackson's attacks on Spanish posts, Monroe recognized that Jackson's campaign left the United States with a stronger hand in ongoing negotiations over the purchase of the Floridas, as it showed that Spain was unable to defend its territories.[115] The Monroe administration restored the Floridas to Spain, but requested that Spain increase efforts to prevent Seminole raids.[116] Some in Monroe's cabinet, including Secretary of War John Calhoun, wanted the aggressive general court-martialed, or at least reprimanded. Secretary of State Adams alone took the ground that Jackson's acts were justified by the incompetence of Spanish authority to police its own territory,[112] arguing that Spain had allowed East Florida to become "a derelict open to the occupancy of every enemy, civilized or savage, of the United States, and serving no other earthly purpose than as a post of annoyance to them."[117] His arguments, along with the restoration of the Floridas, convinced the British and Spanish not to retaliate against the United States for Jackson's conduct.[118] News of Jackson's exploits caused consternation in Washington and ignited a congressional investigation. Clay attacked Jackson's actions and proposed that his colleagues officially censure the general.[119] Even many members of Congress who tended to support Jackson worried about the consequences of allowing a general to make war without the consent of Congress.[120] In reference to popular generals who had taken power through military force, Speaker of the House Henry Clay urged his fellow congressmen to "remember that Greece had her Alexander, Rome her Julius Caesar, England her Cromwell, France her Bonaparte."[121] Dominated by Democratic-Republicans, the 15th Congress was generally expansionist and supportive of the popular Jackson. After much debate, the House of Representatives voted down all resolutions that condemned Jackson, thus implicitly endorsing the military intervention.[122] Jackson's actions in the First Seminole War would be the subject of ongoing controversy in subsequent years, as Jackson claimed that Monroe had secretly ordered him to attack the Spanish settlements, a claim that Monroe denied.[113] Acquisition of Florida Negotiations over the purchase of the Floridas began in early 1818.[123] Don Luis de Onís, the Spanish Minister at Washington, suspended negotiations after Jackson attacked Spanish settlements,[124] but he resumed his talks with Secretary of State Adams after the U.S. restored the territories.[125] On February 22, 1819, Spain and the United States signed the Adams–Onís Treaty, which ceded the Floridas in return for the assumption by the United States of claims of American citizens against Spain to an amount not exceeding $5,000,000. The money was not actually a purchase price.[126] The treaty also contained a definition of the boundary between Spanish and American possessions on the North American continent. Beginning at the mouth of the Sabine River, the line ran along that river to the 32nd parallel, then due north to the Red River, which it followed to the 100th meridian, due north to the Arkansas River, and along that river to its source, then north to the 42nd parallel, which it followed to the Pacific Ocean. The United States renounced all claims to the lands west and south of this boundary, while Spain surrendered its claim to Oregon Country.[124] Spanish delay in relinquishing control of the Floridas led some congressmen to call for war, but Spain peacefully transferred control in February 1821.[127] Latin AmericaEngagement Monroe was deeply sympathetic to the Latin American revolutionary movements against Spain. He was determined that the United States should never repeat the policies of the Washington administration during the French Revolution when the nation had failed to demonstrate its sympathy for the aspirations of peoples seeking to establish republican governments. He did not envisage military involvement but only the provision of moral support, as he believed that a direct American intervention would provoke other European powers into assisting Spain.[128] Despite his preferences, Monroe initially refused to recognize the Latin American governments due to ongoing negotiations with Spain over Florida.[129] In March 1822, Monroe officially recognized the countries of Argentina, Peru, Colombia, Chile, and Mexico.[90] Secretary of State Adams, under Monroe's supervision, wrote the instructions for the ambassadors to these new countries. They declared that the policy of the United States was to uphold republican institutions and to seek treaties of commerce on a most-favored-nation basis. The United States would support inter-American congresses dedicated to the development of economic and political institutions fundamentally differing from those prevailing in Europe. Monroe took pride as the United States was the first nation to extend recognition and to set an example to the rest of the world for its support of the "cause of liberty and humanity".[128] In 1824, the U.S. and Gran Colombia reached the Anderson–Gual Treaty, a general convention of peace, amity, navigation, and commerce that represented the first treaty the United States entered into with another country in the Americas.[130][131] Between 1820 and 1830, the number of U.S. consuls assigned to foreign countries would double, with much of that growth coming in Latin America. These consuls would help merchants expand U.S. trade in the Western Hemisphere.[132] Monroe DoctrineThe British had a strong interest in ensuring the demise of Spanish colonialism, as the Spanish followed a mercantilist policy that imposed restrictions on trade between Spanish colonies and foreign powers. In October 1823, Ambassador Rush informed Secretary of State Adams that Foreign Secretary George Canning desired a joint declaration to deter any other power from intervening in Central and South America. Canning was motivated in part by the restoration of King Ferdinand VII of Spain by France. Britain feared that either France or the "Holy Alliance" of Austria, Prussia, and Russia would help Spain regain control of its colonies, and sought American cooperation in opposing such an intervention. Monroe and Adams deliberated the British proposal extensively, and Monroe conferred with former presidents Jefferson and Madison.[133] Monroe was at first inclined to accept Canning's proposal, and Madison and Jefferson both shared this preference.[133] Adams, however, vigorously opposed cooperation with Great Britain, contending that a statement of bilateral nature could limit U.S. expansion in the future. Additionally, Adams and Monroe shared a reluctance to appear as a junior partner in any alliance.[134] Rather than responding to Canning's alliance offer, Monroe decided to issue a statement regarding Latin America in his 1823 Annual Message to Congress. In series of meetings with the cabinet, Monroe formulated his administration's official policy regarding European intervention in Latin America. Adams in particular played a major role in these cabinet meetings, and the Secretary of State convinced Monroe to avoid antagonizing the members of the Holy Alliance with unduly belligerent language.[135] Monroe's annual message was read by both houses of Congress on December 2, 1823. In it, he articulated what became known as the Monroe Doctrine.[136] The doctrine reiterated the traditional U.S. policy of neutrality with regard to European wars and conflicts, but declared that the United States would not accept the recolonization of any country by its former European master. Monroe stated that European countries should no longer consider the Western Hemisphere open to new colonization, a jab aimed primarily at Russia, which was attempting to expand its colony on the northern Pacific Coast. At the same time, Monroe avowed non-interference with existing European colonies in the Americas.[90][128] The Monroe Doctrine was well received in the United States and Britain, while Russia, French, and Austrian leaders privately denounced it.[137] The European powers knew that the U.S. had little ability to back up the Monroe Doctrine with force, but the United States was able to "free ride" on the strength of the British Royal Navy.[90] Nonetheless, the issuance of the Monroe Doctrine displayed a new level of assertiveness by the United States in international relations, as it represented the country's first claim to a sphere of influence. It also marked the country's shift in psychological orientation away from Europe and towards the Americas. Debates over foreign policy would no longer center on relations with Britain and France, but would instead focus on western expansion and relations with Native Americans.[138] AdamsAdams and Clay sought engagement with Latin America in order to prevent it from falling under the British Empire's economic influence.[139] As part of this goal, the administration favored sending a U.S. delegation to the Congress of Panama, an 1826 conference of New World republics organized by Simón Bolívar.[140] Clay and Adams hoped that the conference would inaugurate a "Good Neighborhood Policy" among the independent states of the Americas.[141] However, the funding for a delegation and the confirmation of delegation nominees became entangled in a political battle over Adams's domestic policies, with opponents such as Senator Martin Van Buren impeding the process of confirming a delegation.[142] Though the delegation finally won confirmation from the Senate, it never reached the Congress of Panama due to the Senate's delay.[143] In 1825, Antonio José Cañas, the Federal Republic of Central America's (FCRA) ambassador to the United States, proposed a treaty to provide for the construction of a canal across Nicaragua.[144] Impressed with the new Erie Canal, Adams was intrigued by the possibility of the canal.[140] The FCRA awarded a contract for the construction of the canal to a group of American businessmen, but the enterprise ultimately collapsed due to lack of funding. The failure of the canal contributed to the collapse of the FCRA, which was dissolved in 1839.[145] Mexico gained its independence shortly after the United States and Spain ratified the Adams–Onís Treaty, and the Adams administration approached Mexico about a renegotiation of the Mexico–United States border.[146] Joel Roberts Poinsett, the ambassador to Mexico, unsuccessfully attempted to purchase Texas. In 1826, American settlers in Texas launched the Fredonian Rebellion, but Adams prevented the United States from becoming directly involved.[147] Adams, trade, and claims One of the major foreign policy goals of the Adams administration was the expansion of American trade.[148] His administration reached reciprocity treaties with a number of nations, including Denmark, the Hanseatic League, the Scandinavian countries, Prussia, and the Federal Republic of Central America. The administration also reached commercial agreements with the Kingdom of Hawaii and the Kingdom of Tahiti.[149] Adams also renewed existing treaties with Britain, France, and the Netherlands, and began negotiations with Austria, the Ottoman Empire, and Mexico that would all lead to successful treaties after Adams left office. Collectively, these commercial treaties were designed to expand trade in peacetime and preserve neutral trading rights in wartime.[150] Adams sought to reinvigorate trade with the West Indies, which had fallen dramatically since 1801. Agreements with Denmark and Sweden opened their colonies to American trade, but Adams was especially focused on opening trade with the British West Indies. The United States had reached a commercial agreement with Britain in 1815, but that agreement excluded British possessions in the Western Hemisphere. In response to U.S. pressure, the British had begun to allow a limited amount of American imports to the West Indies in 1823, but U.S. leaders continued to seek an end to Britain's protective Imperial Preference system.[151] In 1825, Britain banned U.S. trade with the British West Indies, dealing a blow to Adams's prestige.[94] The Adams administration negotiated extensively with the British to lift this ban, but the two sides were unable to come to an agreement.[152] Despite the loss of trade with the British West Indies, the other commercial agreements secured by Adams helped expand overall volume of U.S. exports.[153] The Adams administration settled several outstanding American claims that arose from the Napoleonic Wars, the War of 1812, and the Treaty of Ghent. He viewed the pursuit of these claims as an important component in establishing U.S. freedom of trade. Gallatin, in his role as ambassador to Britain, convinced the British to agree to an indemnity of approximately $1 million. The U.S. also received smaller indemnities from Sweden, Denmark, and Russia. The U.S. sought a large indemnity from France, but negotiations broke down after the government of Jean-Baptiste de Villèle collapsed in 1828.[154] Clay and Adams were also unsuccessful in their pursuit of several claims against Mexico.[155] Other issues and incidentsHaiti After early 1802, when he learned that Napoleon intended to regain a foothold in Saint-Domingue and Louisiana, Jefferson proclaimed neutrality in relation to the Haitian Revolution. The U.S. allowed war contraband to "continue to flow to the blacks through usual U.S. merchant channels and the administration would refuse all French requests for assistance, credits, or loans."[156] The "geopolitical and commercial implications" of Napoleon's plans outweighed Jefferson's fears of a slave-led nation.[157] After the rebels in Saint-Domingue proclaimed independence from France in the new republic of Haiti in 1804, Jefferson refused to recognize Haiti as the second independent republic in the Americas.[158] In part he hoped to win Napoleon's support over the acquisition of Florida.[159] American slaveholders had been frightened and horrified by the slave massacres of the planter class during the rebellion and after, and a southern-dominated Congress was "hostile to Haiti."[160] They feared its success would encourage slave revolt in the American South. Historian Tim Matthewson notes that Jefferson "acquiesced in southern policy, the embargo of trade and nonrecognition, the defense of slavery internally and the denigration of Haiti abroad."[160] According to the historian George Herring, "the Florida diplomacy reveals him [Jefferson] at his worst. His lust for land trumped his concern for principle."[161] Slave tradeIn the 1790s, many anti-slavery leaders had come to believe that the institution of slavery would become extinct in the United States in the foreseeable future. These hopes lay in part on the enthusiasm for the abolition of slavery in the North, and in the decline of the importation of slaves throughout the South. The Constitution had included a provision preventing Congress from enacting a law banning the importation of slaves until 1808.[162] In the years before Jefferson took office, the growing fear of slave rebellions led to diminished enthusiasm in the South for the abolition of slavery, and many states began to enact Black Codes designed to restrict the behavior of free blacks.[163] During his presidential term, Jefferson was disappointed that the younger generation was making no move to abolish slavery; he largely avoided the issue until 1806. He did succeed in convincing Congress to block the foreign importation of slaves into the newly purchased Louisiana Territory.[164] Seeing that in 1808 the twenty-year constitutional ban on ending the international slave trade would expire, in December 1806 in his presidential message to Congress, Jefferson called for a law to ban it. He denounced the trade as "violations of human rights which have been so long continued on the unoffending inhabitants of Africa, in which the morality, the reputation, and the best interests of our country have long been eager to proscribe." Jefferson signed the new law and the international trade became illegal in January 1808. Britain at the same time made the international trade illegal.[165] The legal trade had averaged 14,000 slaves a year; illegal smuggling at the rate of about 1000 slaves a year continued for decades.[166] "The two major achievements of Jefferson's presidency were the Louisiana Purchase and the abolition of the slave trade," according to historian John Chester Miller.[167] Russo-American TreatyIn the 18th century, Russia had established Russian America on the Pacific coast. In 1821, Tsar Alexander I issued an edict declaring Russia's sovereignty over the North American Pacific coast north of the 51st parallel north. The edict also forbade foreign ships to approach within 115 miles of the Russian claim. Adams strongly protested the edict, which potentially threatened both the commerce and expansionary ambitions of the United States. Seeking favorable relations with the U.S., Alexander agreed to the Russo-American Treaty of 1824. In the treaty, Russia limited its claims to lands north of parallel 54°40′ north, and also agreed to open Russian ports to U.S. ships.[168] References

Works cited

Further reading

Primary sources

|