|

Notiomastodon

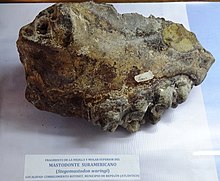

Notiomastodon is an extinct genus of gomphothere proboscidean (related to modern elephants), endemic to South America from the Pleistocene to the beginning of the Holocene.[1] Notiomastodon specimens reached a size similar to that of the modern Asian elephant, with a body mass of 3-4 tonnes. Like other brevirostrine gomphotheres such as Cuvieronius and Stegomastodon, Notiomastodon had a shortened lower jaw and lacked lower tusks, unlike more primitive gomphotheres like Gomphotherium. The genus was originally named in 1929, and has been controversial in the course of taxonomic history as it has frequently been confused with or synonymized with forms called Haplomastodon and Stegomastodon. Extensive anatomical studies since the 2010s have shown that Notiomastodon represents the only valid proboscidean in lowland South America, Haplomastodon is synonymous and Stegomastodon is limited to North America, with the only other gomphothere in South America Cuvieronius confined to the northwestern part of the continent. Notiomastodon arrived in South America along with many other animals of North American origin as part of the Great American Interchange following the formation of the Isthmus of Panama connecting the two continents during the Pliocene epoch. Notiomastodon ranged widely over most of South America, from Colombia in the northwest to Northeast Brazil and southwards to the Zona Sur in Chile. It is thought to have been a generalist mixed feeder that fed on a variety of plants, with its diet varying according to local conditions. Like living elephants, Notiomastodon is thought to have lived in family groups, with adult males suggested to have had musth-like behaviour. Notiomastodon became extinct approximately 11,000 years ago at the end of the Pleistocene epoch, simultaneously along with the majority of large (megafaunal) animals native to the Americas as part of the end-Pleistocene extinction event. During the last few thousand years of its existence, Notiomastodon lived alongside Paleoindians, the first human to inhabit the Americas. Specimens associated with artifacts suggest that humans hunted Notiomastodon, which may have been a factor in its extinction. Research historyInitial research Traditionally, several species of gomphotheres from the late Pleistocene in South America were distinguished. These included, on the one hand, a highland form from the Andes, Cuvieronius, whose classification has not been controversial, and, on the other hand, several forms present in the lowlands, such as Haplomastodon and Notiomastodon. In addition to this is Stegomastodon, which has a North American distribution. The relationships of the three genres with each other on their independence or synonymization have been the subject of continuous discussion. Research on South American proboscideans began with the expeditions of Alexander von Humboldt in the transition from the 18th to the 19th century. From his collection of finds, Georges Cuvier published two teeth in 1806, one of which came from the vicinity of the Imbabura Volcano near Quito in Ecuador, and the other from Concepción in Chile. Cuvier did not give them scientific names that are valid today, but simply called the first in French "Mastodon des cordilléres" and the second "Mastodon humboldien".[2] In 1814, Gotthelf Fischer von Waldheim coined for first time scientific names for the South American proboscideans by renaming Cuvier's "Mastodon des cordilléres" as Mastotherium hyodon and "Mastodon humboldien" as Mastotherium humboldtii.[3] Cuvier himself would refer both species to the now-disused genus "Mastodon" in 1824, but created a new name of species for the Ecuadorian find which is "Mastodon" andium (he placed the Chilean find in "Mastodon" humboldtii).[4] From the present point of view, both teeth do not have specific diagnostic characteristics that allow them to be assigned to a species in particular. In the following years, the number of discovered fossils increased, which led Florentino Ameghino in 1889 to give the first general review of the proboscideans in his extensive work on the extinct mammals of Argentina. In this he listed several species, all of which he considered analogous to Cuvier's "Mastodon". In addition to the species already created by Cuvier and Fischer, Ameghino named some new ones, including "Mastodon" platensis, which he had already established a year earlier and whose description was based on a tusk fragment of an adult individual from San Nicolás de los Arroyos in the province of Buenos Aires, on the shores of the Paraná River, (catalog number MLP 8-63).[5][6] Henry Fairfield Osborn used "Mastodon" humboldtii in 1923 to include it in the new genus Cuvieronius (another genus name he created in 1926, Cordillerion based on "Mastodon" andium, is now considered a synonym of Cuvieronius).[7][8] Forty years after Ameghino, Ángel Cabrera reviewed the proboscidean finds. He named the genus Notiomastodon,[nb 1] "southern mastodon" and assigned to it the new species Notiomastodon ornatus, of which he had found a mandible and another tusk fragment at Playa del Barco near Monte Hermoso also in Buenos Aires province (catalog number MACN 2157). For his part, he assigned Ameghino's "Mastodon" platensis to Stegomastodon and synonymized this species with some of the names previously proposed by Ameghino.[10] The genus Stegomastodon itself dates back to Hans Pohlig in 1912, who referred it to some findings of North American mandible.[11][12]  In the northernmost part of South America, Juan Félix Proaño discovered in 1894 an almost complete skeleton near Quebrada Chalán, in the vicinity of Punín in the Ecuadorian province of Chimborazo. The skeleton he named as the new species "Masthodon" chimborazi in 1922. However, in 1929 it was almost completely lost in a fire at the University of Quito, along with another skeleton recovered at Quebrada Callihuaico near Quito a year earlier. In 1950, Robert Hoffstetter used the right and left humeri of the Quebrada Chalán skeleton to name Haplomastodon, which he considered to be a subgenus of Stegomastodon. As type species he assigned Haplomastodon chimborazi (catalog numbers MICN-UCE-1981 and 1982); in 1995 Giovanni Ficcarelli et al. identified a neotype with catalog number MECN 82 to 84 from Quebrada Pistud in the Ecuadorian province of Carchi, which also included a complete skeleton.[13] Only two years later Hoffstetter raised Haplomastodon to the level of the genus, and the main criterion for distinguishing it from Stegomastodon being the absence of a transverse opening in the atlas (first cervical vertebra). Simultaneously, he distinguished two more subgenera, Haplomastodon and Aleamastodon, which he differentiated from each other by the absence and presence of said openings in the axis, respectively.[14] Stegomastodon, Notiomastodon and HaplomastodonSince the establishment of Stegomastodon by Pohlig in 1912, Notiomastodon by Cabrera in 1929, and Haplomastodon as an independent genus by Hoffstetter in 1952, there have been multiple discussions about the validity of these three taxa.[15] As early as 1952, Hoffstetter had limited Haplomastodon to northwestern South America, while for the remaining finds such as those from Brazil, he preferred to place them within Stegomastodon. This was reviewed by George Gaylord Simpson and Carlos de Paula Couto in 1957 in their extensive work Mastodonts of Brazil. In this, both authors referred all the Brazilian finds to Haplomastodon. They determined that the other two genera, Notiomastodon and Stegomastodon, were found further to the southeast in the Pampas region. The features of the transverse foramina of the first cervical vertebra, which Hoffstetter applied to distinguish Haplomastodon from Stegomastodon, turned out to be highly variable, even in the same individual, according to the investigations of Simpson and Paula Couto. Therefore, both highlighted as a diagnostic feature of Haplomastodon compared to Notiomastodon and Stegomastodon the much more upwardly curved upper tusks, which do not present any layer of enamel. Simpson and Paula Couto established Haplomastodon waringi as the type species of the genus.[16] The designation of this species refers to "Mastodon" waringi, a taxon coined by William Jacob Holland in 1920. This was based on a highly fragmented remains of a jaw found in Pedra Vermelha in the Brazilian state of Bahia,[17] and because it was named much earlier, Simpson and Paula Couto argued and in accordance with ICZN nomenclature rules, this name has priority over Haplomastodon chimborazi.[16] However, the validity of the designation of this species was frequently criticized, including by Hoffstetter himself, given that the material from Brazil is of little significance due to its poor preservation status. Other authors followed this idea and considered Haplomastodon chimborazi as the valid name (although in 2009 the taxon "Mastodon" waringi was preserved by the ICZN due to its multiple mentions in the scientific literature[18]).[19][14][16] In 1995, Maria Teresa Alberdi and José Luis Prado synonymized Notiomastodon with Stegomastodon, leaving Stegomastodon platensis as the valid species. In the same study they also synonymized Haplomastodon with Stegomastodon creating the combination Stegomastodon waringi. According to his vision, in his time Stegomastodon was the only gomphotherid genus present in the South American lowlands.[20] However, in 2008 Marco P. Ferretti defended the independent classification of Haplomastodon, but at the same time questioned the separation of Notiomastodon respect to Stegomastodon.[21] Only two years later, he published an exhaustive work focused on the anatomy of the skeleton of Haplomastodon, in which he clearly separated it from Stegomastodon and gave it an intermediate position between it and Cuvieronius in the Andes.[14] Around the same period, Spencer George Lucas and collaborators reached a similar conclusion, especially after examining an almost complete skeleton of Stegomastodon from the Mexican state of Jalisco and determined that this genus should be separated from the South American gomphotheres due to its different musculoskeletal characteristics. They differentiated Notiomastodon from Haplomastodon due to the much more complex chewing surface of their molariforms. According to this, there would be at least two species of gomphotheres living in the lowlands of South America.[22][23][24] Analysis by a team of researchers led by Dimila E. Mothé in the early 2010s gave a different result. After examining abundant material from South American proboscideans, they determined that apart from Cuvieronius, there was only one other genus of proboscidean in South America during the Pleistocene. In their opinion, this animal showed great variability in relation to the morphology of the teeth and skull, mainly in the shape of the tusks and molariform teeth. By following the ICZN priority rules, the first genus name given to this gomphothere, which would be Notiomastodon, remains valid, and with only one species which must be called Notiomastodon platensis.[25][26] This is the classification that has been adopted at various times in the following years, and Mothé and colleagues through extensive morphological analysis of the teeth and skeletons, found that Stegomastodon differed significantly from Notiomastodon and was confined to North America.[27][12][28] Later, Spencer George Lucas also supported this idea.[29] However, some authors as Alberdi & Prado considered this is inconclusive, as they think the North American Stegomastodon material is too scarce and fragmentary to make a definitive statement.[30] However, in a review about the fossil record of gomphotherids in South America published in 2022, both authors agreed to call it Notiomastodon.[31] AmahuacatheriumEspecially problematic is the genus Amahuacatherium, which was described in 1996 by Lidia Romero-Pittman based on a fragmented mandible and two isolated molars found in the Madre de Dios region of southeastern Peru. The findings come from the Ipururo Formation, which outcrops along the Madre de Dios River. However, a partial skeleton that had been discovered along with these fossils was lost during a violent flood. As a special feature of Amahuacatherium, the authors highlighted the short mandible with sockets for rudimentary incisors and molars with moderately complex molar masticatory surface pattern. The age of the sedimentary layers of these fossil remains is estimated at 9.5 million years, which corresponds to the late Miocene. This would make Amahuacatherium one of the first mammals to reach South America from the north before the Great American Biotic Interchange, which would only begin about six million years later.[32] Additionally, this find is much older than the gomphotherid evidence considered as the oldest in both Central and South America, dating back to 7 and 2.5 million years, respectively. Only a few years later, several authors expressed doubts about the identity of this genus and its age. For example, their molars were considered to be barely distinguishable from other South American gomphotheres and the presence of alveoli for the lower tusks would be a misinterpretation of the mandibular cavities. Geologic age is also difficult to determine due to the complex stratigraphic conditions at the site.[33][34] Other scientists agreed with this,[29] and further dental analysis revealed no significant differences with Notiomastodon, relative to the other South American finds.[27] ClassificationPhylogenyThe following cladogram shows the placement of the Notiomastodon among Late Pleistocene and modern proboscideans, based on genetic data:[35][36]

Notiomastodon is a genus of proboscidean in the family Gomphotheriidae. The proboscideans are a relatively successful mammalian order with a long history, which began at the end of the Paleocene. Originally from Africa, they reached a great diversity and expansion in both the Old and the New World in the course of their evolutionary history. Different phases of evolutionary radiation can be distinguished. The gomphotheres belong to the second phase, which began in the lower Miocene. The main characteristic of true gomphotheres is the formation is the formation of three transverse ridges on first and second molars (trilophodont gomphotheres; later forms with four tusks are sometimes known as tetralophodont gomphotheres, but are no longer included in the family). As in extant elephants, gomphotheres had a horizontal tooth replacement pattern which includes them in the modern group Elephantimorpha, compared to their ancestors which lacked this trait.[37] In contrast to vertical tooth replacement which is used for most mammals, in which all permanent teeth are available at the same time, in horizontal replacement the individual molariform teeth erupt one after another in a row. This originated from jaw shortening in the course of proboscidean evolution and is first detectable in Eritreum in the late Oligocene, about 28 million years ago. Still, unlike modern elephants, gomphotheres possess a number of primitive and advanced traits. These include, for example, a generally flatter skull, the formation of upper and lower fenders as well as molariform teeth with fewer ridges and a mamelonated masticatory surface pattern. For this reason, gomphotheres are often placed in their own superfamily, the Gomphotherioidea,[38] which is sister to the modern Elephantoidea. However, they are sometimes considered to be members of the Elephantoidea.[39] In general, the gomphotheres are one of the most successful groups among the proboscideans, which underwent numerous changes in their long existence. These include a substantial increase in their overall size, their tusks and their molar teeth, as well as an increase in their complexity.[40] Notiomastodon is a genus of proboscidean in the family Gomphotheriidae. The proboscideans are a relatively successful mammalian order with a long history, which began at the end of the Paleocene. Originally from Africa, they reached a great diversity and expansion in both the Old and the New World in the course of their evolutionary history. Different phases of evolutionary radiation can be distinguished. The gomphotheres belong to the second phase, which began in the lower Miocene. The main characteristic of true gomphotheres is the formation of three transverse ridges on first and second molars (trilophodont gomphotheres; later forms with four tusks are sometimes known as tetralophodont gomphotheres, but are no longer included in the family). As in extant elephants, gomphotheres had a horizontal tooth replacement pattern which includes them in the modern group Elephantimorpha, compared to their ancestors which lacked this trait.[37] In contrast to vertical tooth replacement which is used for most mammals, in which all permanent teeth are available at the same time, in horizontal replacement the individual molariform teeth erupt one after another in a row. This originated from jaw shortening in the course of proboscidean evolution and is first detectable in Eritreum in the late Oligocene, about 28 million years ago. Still, unlike modern elephants, gomphotheres possess a number of primitive and advanced traits. These include, for example, a generally flatter skull, the formation of upper and lower fenders as well as molariform teeth with fewer ridges and a mamelonated masticatory surface pattern. For this reason, gomphotheres are often placed in their own superfamily, the Gomphotherioidea,[38] which is sister to the modern Elephantoidea. However, they are sometimes considered to be members of the Elephantoidea.[39] In general, the gomphotheres are one of the most successful groups among the proboscideans, which underwent numerous changes in their long existence. These include a substantial increase in their overall size, their tusks and their molar teeth, as well as an increase in their complexity.[40]

Gomphotheres are first recorded at the end of the Oligocene in Africa and are among the first representatives of the proboscideans to leave that continent after the closure of the Tethys Ocean and the appearance of the land bridge to Eurasia during the transition to the Miocene. Among others, Gomphotherium reached North America about 16 million years ago through the Bering Strait, while in Central America they are recorded as early as the end of the Miocene about 7 million years ago. Gomphotherids reached South America during the Great American Interchange between 3.5 and 2.5 million years ago. South American gomphotheres differ from their relatives in other parts of the world by their relatively short snouts (brevirostral gomphotheres) and high-domed skulls. Additionally, they only had upper tusks. The two known South American genera (Notiomastodon and Cuvieronius) together with their North American relative (Stegomastodon) form a monophyletic group known as the subfamily Cuvieroniinae,[38] which in turn are grouped with Rhynchotherium in a larger group called Rhynchotheriinae.[41] Some researchers have proposed the idea that Cuvieronius is a direct descendant of Rhynchotherium, as evidenced by its highly specialized upper tusks, which feature a spiral enamel band. Notiomastodon could have descended directly from Cuvieronius. The idea is supported by the recognition that unlike adult specimens, juvenile Cuvieronius still had lower tusks, while in Rhynchotherium the mandible has lower tusks at all ages. This idea does not take into account relationships with other short-faced gomphotherids which are mostly unclear. The situation of Sinomastodon, an East Asian form with skeletal characteristics very similar to South American gomphotheres, is problematic. In several phylogenetic studies, Sinomastodon forms a group with Stegomastodon, Cuvieronius and Notiomastodon, for which its presence in Asia is interpreted as a migration from America.[42][43][44][28] Due to its geographic isolation from the American genera, the Chinese scientists usually place it in the independent subfamily Sinomastodontinae.[45] Taking into account the lack of intermediate forms, some authors consider the similarities between Sinomastodon and the South American gomphotheres to be the result of convergent evolution.[29] As with many mammals known only from fossils, phylogenetic relationships are inferred from skeletal anatomical features. It is only since the 2000s that methods based on molecular genetics and biochemical analyzes have gradually acquired a greater role. In addition to the woolly mammoth (Mammuthus primigenius), the Columbian mammoth (Mammuthus columbi) and the straight-tusked elephant (Palaeoloxodon antiquus) which are members of the modern family Elephantidae, the American mastodon (Mammut americanum) of the family Mammutidae is the only non elephantid proboscidean whose molecular data has been sequenced.[46][47][48] Notiomastodon is the only representative of the gomphotheres for which biochemical data are available for comparison. In stark contrast to what was suspected of its close anatomical resemblance to elephantids, a study published in 2019 indicated a closer relationship to mastodonts. It is unclear whether this result can be extrapolated to the rest of the entire group of gomphotherids.[49] On the other hand, a 2021 study based on mitochondrial DNA determined that Notiomastodon is more closely related to modern elephants than to Mammut.[36] Within this genus, only one species is recognized:[27][12][28]

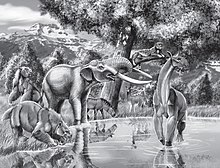

Various other forms have been described throughout history, some of them associated with Notiomastodon (N. ornatus), some also with Haplomastodon (H. waringi, H. chimborazi), but are now considered more recent synonyms of N. platensis.[27][12][28] Evolutionary historyThe appearance of gomphotherids in South America originates with the Great American Interchange. This began in the Pliocene about 3.5 million years ago, when the Isthmus of Panama closed and a mainland connection between North and South America was established.[50] This exchange occurred in both directions, so that for example ground sloths and glyptodonts arrived in the north, while carnivorous mammals and artiodactyls, as well as proboscideans, among others, mixed with the endemic fauna of the south. The oldest record of proboscideans from South America comes from the middle section of the Uquia Formation in northwestern Argentina. It dates from about 2.5 million years ago,[51] and the findings, which correspond to fragmentary remains of vertebrae, are not attributable to a particular genus.[52][23] It is unknown when Notiomastodon originated. There are no clear documented finds of this genus in Central America. On another hand, Cuvieronius appeared in the region about 7 million years ago.[23] It has been generally assumed that the gomphotherids invaded South America in two independent waves. Cuvieronius used a corridor west of the Andes, while Notiomastodon used an eastern one along the Atlantic coast and lowlands.[20][34][43] It is possible that the emigration to South America was much more complex, since Cuvieronius does not show a restriction to the highlands in Central America, but can also be found there in lowlands.[27] The oldest unambiguous evidence of Notiomastodon in South America is an individual tooth found on the continental shelf off the Brazilian coast in the state of Rio Grande do Sul, which was radiometrically dated to 464,000 years ago and therefore corresponds to the Middle Pleistocene.[53] The vast majority of Notiomastodon finds belong to the late Middle Pleistocene and Late Pleistocene. Its distribution areas in central Chile may have been reached relatively late, either by a route from the Pampas to the low inter-Andean valleys or from the north through the Amazonian lowlands. This may have occurred during the warm periods of the last glacial period, when the Patagonian ice cap was less extensive.[54][55] DescriptionSize Notiomastodon was a medium to large proboscidean. A complete skeleton was reconstructed a height at the withers of about 2.5 meters and a body weight of 3.15 tons,[14] while other analyzes put the weight of the same individual at more than 4.4 tons.[56] For another individual, the weight calculations vary between 4.1 and 7.6 tons. Since these estimates are based on the dimensions of the limb bones, but these differ proportionally from those of extant elephants, these values can only be considered as an approximation.[57][58] In general, this genus reached approximately the dimensions of current Asian elephants (Elephas maximus). A partial femur head from Yumbo in Colombia, with a circumference of 51.2 cm, suggests that this specimen could have exceeded 7.9 tons in weight;[59] some specimens could reach 3 meters in height.[34] Skull and teethNotiomastodon's skull was short and tall, and compared to that of its relative Cuvieronius, it was narrower and shorter. In side view, this was pronounced in a dome, comparable to that of the skulls of today's elephants. However, in the case of modern elephants, the skull has an even more upright orientation and the snout is much shorter. The skulls found have total lengths of 75 to 113 cm, and the height of these, measured from the upper edge to the dental alveoli, is 41 to 76 cm.[60] The upper part of the skull was characterized in frontal view by having two domes, between which is a slight suture along the center of the skull. Both domes were formed by the air-filled chambers of the neurocranium. These were larger than in Gomphotherium. The forehead was broad and flattened for the most part. As in all advanced proboscideans, the nasal bone was short and lay on top of the very wide but flat nasal opening where the trunk connected to the skull. Seen from the side, a groove bounded the nasal bone, which served as an anchor point for the maxillolabial muscle, which acted as a load-bearing arm for the tube. The remaining edges of the nasal opening were formed by the premaxillary bone and individual extensions of it. This bone also formed the alveoli of the upper incisors. These were very long, sometimes up to 59 cm, and they were very wide and their diameter increased towards the front. These only diverged slightly and in side view aligned with the profile of his forehead. This created a wide angle between the orientation of the tusks sockets and the plane of the chewing surface of the molars. Upwards, the alveoli of the incisors were slightly indented. In general, the premaxilla was much more massive than in Gomphotherium, for example. Due to the shortening of the skull at the snout, the eye orbit of Notiomastodon was above the front end of the molar tooth row, which is markedly more forward than in long-snouted gomphotheres such as Gomphotherium or Rhynchotherium. The zygomatic arch was robust and high. Its upper border was rather straight, while the lower one had a slight notch in which the masseter muscle began.[14][28]   The jaw reached 77 cm in length, and the area where the teeth were inserted was quite wide and noticeably arched at its lower edge. The height under the molars was more than 15 cm. In contrast, Stegomastodon had a mostly straight lower border. The symphysis was typical of South American gomphotheres as it was relatively short (brevirostral), and in some individuals it pointed downwards and sometimes formed a small prominence, as is the case in Cuvieronius. Downward directed symphysis is considered a diagnostic feature. On the other hand, in Stegomastodon, this prominence was significantly reduced. In some cases, there were as many as three holes known as mental foramina. The ascending ramus of the mandible was massive and rose up to 47 cm. The leading and trailing edges showed a parallel orientation. The frontal process was significantly lower than that of the joint, which was not the case in Stegomastodon. The joint ended transverse to the longitudinal axis of the mandible and was very robust, with a distance between its tips from side to side of 57 cm. Also unlike Stegomastodon, the angular process was less prominent.[14][28] The teeth consisted of its large tusks and the molariform teeth. In contrast to Eurasian gomphotheres, incisors were only formed in the upper dentition, although small sockets were sometimes formed in the lower jaw. As in all proboscideans, the upper tusks were actually hypertrophied second incisor teeth. These tusks could vary in shape in each individual, so that the tusks could be short and with the tips clearly curved upwards or relatively straight. The enamel layer disappears in adult individuals. This differentiates it from Cuvieronius, whose upper tusks were spiraled with an enamel band that wrapped around them. Additionally, in the latter, lower tusk appear in juveniles.[23][29][44] In general, the tusks of Notiomastodon were very robust. Their lengths could reach more than 88 cm outside the alveoli, and in particularly long specimens it could reach 128 cm measured on the external curvature. The cross section was oval in shape and varied from 11.5 to 16.4 cm in diameter.[61] The remaining dentition was composed of the premolars and molars as in modern elephants, which erupted one after the other due to the horizontal replacement of the teeth. The chewing surface was generally composed of seven pairs of ridges or lophs, which gave the teeth a bunodont pattern. The first two molars had three pairs of ridges (trilophodonts) that were oriented along the longitudinal axis. The upper three, meanwhile, had four and the lower one more than five pairs of ridges (tetra- and pentalophodont), so these additional ridges were less pronounced. Stegomastodon, on the other hand, had five ridges on the upper teeth and more than eight on the lower ones. The upper and lower third molars (M3/m3) were tetralophodont or pentalophodont; and their wear morphology in the occlusal phase varies from simple to complicated due to the presence of central conules and accessory conules between the main cusps of pre- and postrites,[60] which makes it look like a double trefoil.[62] It is characteristic of this species is a greater proportion of teeth with these very complex trefoil figures and marked ptychodonty in their enamel. Additionally, two morphotypes can be identified in Notiomastodon in relation to molars, one with two additional central ridges on each half side of the tooth longitudinally and one without. Also very characteristic is the cloverleaf structure on the individual ridges in the weathered state. In general, the dental structure of Notiomastodon was characterized by a basal pattern, which was more similar to that of Cuvieronius. However, due to the different morphotypes, it more closely approximated the complex pattern of the chewing surface of Stegomastodon, which was formed mainly by the formation of additional lateral ridges. The last chewing molar would have had between 35 and 82 ridges in Notiomastodon, 33 and 60 in Cuvieronius, and 57 and 104 in Stegomastodon. In total, the chewing surface of the last molar in Notiomastodon was 57 to 160 cm² (12 to 32 cm² per lophid) and in Stegomastodon 72 to 205 cm² (12 to 34 cm² per lophid). Thus the teeth were typical for a relatively large proboscidean. The lower last molar was 21.6 cm long, and the upper last molar was over 19.3 cm.[14][27][28] Postcranial skeletonIn terms of the shape of its postcranial skeleton, Notiomastodon was for the most part similar to living elephants, but generally stockier. The humerus was massive and 78 to 87 cm long. This widened towards the ends of the joints, the joint head was wide and clearly rounded. However, only some prominences showed rough areas on the axis. The ulna was rather gracile, with a total length of 75 to 80 cm but almost as large as the humerus. Due to the large olecranon, the superior joint extension, the length of the bone was only 57 to 64 cm. As a result, the ulna was functionally much shorter than the humerus, which is characteristic of South American gomphotheres compared to their Eurasian relatives. The physiological length of the ulna also corresponded to the approximate total length of the radius. The femur was 96 to 100 cm long and consisted of a nearly cylindrical shaft, slightly flattened only at the front and back. The spherically shaped femoral head towered over the other prominence, but sat on a shorter neck than that of Cuvieronius.[24] At the lower end, the prominence internal was greater than the external. The fibula, which was up to 70 cm long, was characterized by a prismatic axis and a higher end at the lower joint. The hands and feet had five fingers, as in modern elephants. The limbs of Notiomastodon, like those of other short-jawed gomphotheres, were generally more massive and robust than in extant elephants. It is also very curious that the length of the upper and lower sections of the legs of Notiomastodon were more balanced with each other than those of modern elephants and Stegomastodon. In the case of the latter, the length of the femur exceeded that of the tibia by almost twice. Another important difference can be seen in the ratio of the front legs compared to the hind legs. These have an average of 82% for Notiomastodon and 93% for Stegomastodon, which means that the hind legs of the latter were significantly shorter than the front ones. In Stegomastodon, the ratio of the upper and lower sections of its legs as well as the fore and hind legs to each other gave it a better adaptation for open environments and long strides and a greater degree of graviportality, than in the case of Notiomastodon. This is also reflected in the build of the feet, which were slimmer and taller than in Stegomastodon.[14][24][28] PaleobiologyDietThe bunodont chewing pattern of gomphotheres is usually associated with a generalist diet, which suggests a preference for mixed feeding on both grass and foliage. This has also been delineated in studies on traces of wear and scratches on Notiomastodon molars from the Upper Pleistocene site of Aguas de Araxin Island in the Brazilian state of Minas Gerais. The teeth exhibit a high number of nicks and scratches, which is consistent with similar abrasion marks on the teeth of extant ungulates that consume both hard and soft plants. Through some plant residues from the teeth, it was possible to identify that the basis of their diet were conifers, knotweed plants and polypodiacean ferns.[63] In contrast, isotope analyzes of other areas of South America paint a more complex picture. This results in a predominance of C4 plants in the dietary spectrum of Upper Pleistocene specimens from northern and central South America such as Ecuador or the Gran Chaco, while those from southern regions such as the Pampas fed mostly on C3 plants.[64][34] In the intermediate areas, a mixed diet could be reconstructed based on the isotopes.[65] Specimens from Mato Grosso indicate N. platensis had a generalised browsing diet in that region,[66] with N. platensis from Paraíba similarly being identified as mixed feeders during isotopic analysis.[67] The dietary flexibility of N. platensis was particularly apparent in the fossil finds from the Quequen Grande site in the Argentine province of Buenos Aires. Isotope studies of finds there from the Middle Pleistocene indicate a relatively mixed diet, while others from the Late Pleistocene suggest that it specialized in consuming grasses.[68][63] Remains near Santiago del Estero from the Last Glacial Maximum show a diet exclusively composed of C4 plants.[60] Notiomastodon may have been an opportunistic herbivore adapting its habits food to local conditions, similar to what has been documented in living elephants. Especially during the course of the Late Pleistocene, when climatic changes from the last glacial period in the Southern Cone caused forests to shrink and be replaced by grassland environments, this was an important adaptive phenomenon.[63] PalaeopathologyPathological vertebrae belonging to N. platensis have been found in Late Pleistocene deposits at Anolaima, Cundinamarca, Colombia. Specifically, they consist of deep bone lesions on the spinous process, osteoarthritic lesions, and asymmetrical articulations of the zygaphophyses, which were caused by nutrient deficiencies caused by environmental perturbations and likely exacerbated by excessive biomechanical stress on the bones as the proboscidean moved through the uneven, upland terrain of the region.[69] Late Pleistocene N. platensis fossils from Águas de Araxá in Brazil have been shown to exhibit Schmorl's node, osteoarthritis, and osteomyelitis.[70] The teeth of N. platensis reveal the species was relatively susceptible to the development of dental tartar.[71] Population structure and reproductionLike modern elephants, Notiomastodon is suggested to have lived in social family groups.[72] The Águas de Araxá site is significant as it has one of the largest collections of Notiomastodon fossils. These are interpreted as the remains of a local population that was wiped out by a catastrophic event. According to dental studies, the group consisted of 14.9% juveniles (0 to 12 years of age), 23.0% near-adult individuals (13 to 24 years of age), and 62.1% of adult individuals (25 years of age and older). This last group can be broken down into 27.7% of middle-aged animals (25 to 36 years) and 17.2% of old (37 to 48 years) and senile (49 to 60 years) specimens. The large proportion of individuals over 37 years of age is notable, suggesting that there was a high survival rate in this group.[72] Some of the adult animals suffered from pathological changes in their bones from Schmorl's nodes, osteomyelitis and osteoarthritis. These are evident in the vertebrae and long bones among others, and may be due to individual diseases. Osteomyelitis has also been diagnosed in Notiomastodon finds from other sites.[73][74] The remains found at Águas de Araxá must have been exposed for a long time after their deposit. Not only did this allow dermestid beetles to bore into the bones, but there is also evidence of bite marks from large canids such as Protocyon. The gnawed bone marks are the result of carrion consumption, possibly caused by a period of food scarcity. Due to its size, Notiomastodon would hardly have natural enemies in life.[75][76] Traces left by a large predator were also found on a skeleton from the Pilauco site in southern Chile.[77] A study of the tusk of a male animal from the Santiago de Chile basin allowed the analysis of the last four years of its life by means of isotope and thin-section analyses. During this period, tusk appositional thickness increased by about 10 mm per year. This growth rate was found to be cyclical, slowing briefly in early summer with reduced tooth growth. The reduced growth is interpreted to correspond to the musth stage, a hormone-controlled phase that occurs annually in modern elephants and is characterized by a huge increase in testosterone. During the musth, males become extremely aggressive and battles for mating rights can ensue, sometimes with fatal consequences. An external feature is the increased flow of a secretion from the temporal gland. In the case of the animal from Santiago de Chile, growth abnormalities were partially linked to a change in diet. The individual's death took place relatively abruptly in early autumn.[78] IchnofossilsProboscidean footprint fossils documented in South America are relatively rare. One of the most important sites is Pehuen Có near Bahía Blanca in the Argentine province of Buenos Aires. The site was discovered in 1986 and covers an area of 1.5 km2. The numerous footprints were printed on a substrate that was originally soft. It has been possible to identify several ichnogenera produced by mammals, such as Megalamaichnum (corresponding to the camelid Hemiauchenia), Eumacrauchenichnus (from the native ungulate Macrauchenia), Glyptodontichnus (produced by the armadillo relative Glyptodon) or Neomegatherichnum (the giant sloth Megatherium), and additionally, footprints of birds such as Aramayoichnus, which would represent a rhea, have also been found. Due to the diversity of footprints, Pehuen Có is one of the most important sites with ichnofossils in the world. It has been dated to about 12,000 years before present. Proboscidean tracks, however, are not common there. The main trail comprises seven footprints over a length of 4.4 meters. The individual prints have an oval shape with lengths from 23 to 27 cm and widths from 23 to 30 cm. In general, these have a depth of 8 cm below the surface. In some cases, small prominences are found on the front edge, which are interpreted as markings of three to five fingers, comparable to the nail-shaped structures of living elephants. The largest frontal footprints have five, and those of the smallest in some cases only have three of those prominences. In the same way they have a flattened shape that was generated by the fat pads of the legs as it happens in modern elephants. The footprints of Pehuen Có are assigned to the ichnogenus Proboscipeda, whose synonym is Stegomastodonichnum. The size of these footprints suggests that they were made by animals the size of the Asian elephant, roughly matching Notiomastodon.[79] Distribution The geographic range of Notiomastodon extended through northern, eastern, and southern South America, with its southernmost distribution limit between the latitudes of 37 and 38 south.[80][34] The specimens of this proboscidean are found mostly in the lowlands, while in the mountainous areas of the Andes it was largely absent, with Cuvieronius present in these regions instead. It is possible that both proboscideans avoided direct competition due to the strict definition of habitat, since both had a similar ecological spectrum.[27] Modern elephants also generally avoiding higher elevation areas due to the associated energy cost of traversing them. In Colombia, it is suggested that Notiomastodon migrated through inter-Andean valleys.[81] Many fossils of Notiomastodon have been found in the Pampas region and the Gran Chaco in Argentina. These include deposits such as Santa Clara del Mar in the province of Buenos Aires and the Río Dulce in the province of Santiago del Estero.[82][60] Remains have also been documented from southern Bolivia, which are still found in the Gran Chaco area. Otherwise, most of the finds from that area correspond to Cuvieronius.[83] The southernmost evidence of this proboscidean comes from isolated remains from Chile,[54][55] with the southernmost remains in the country being from Chiloé Island.[84] There are several findings in Uruguay[85][86] and Paraguay.[10][16] Other finds are known from Brazil, where Notiomastodon was widely distributed from the open areas of the southern Chaco to the current Amazon basin, and fossil remains have been found on the continental shelf of the Atlantic coast.[53][87][88] One of the sites most important, however, is the state of Minas Gerais. At least 47 Notiomastodon individuals were found there. These were preserved in a sinkhole with coarse-grained sediments.[72][63] The genus has also been reported from Peru,[33] Ecuador,[19] Colombia,[89][90] and Venezuela.[91] Is interesting to note that some of the localities with Notiomastodon remains in these countries, as Nemocón in Colombia, Punín, in Ecuador and Leclishpampa, Lima in Peru, are located in high mountain deposits, meanwhile that in La Huaca in Peru, a lowland environment, has been found remains of Cuvieronius, in contrast with the traditional division between lowland/mountain habitats for these animals.[27] In Ecuador, the Quebrada Pistud site near Bolívar in the province of Carchi is noteworthy. This contained about 160 Notiomastodon fossil remains housed over several dozen square meters in flood deposits. These represented at least seven specimens, and a single skeleton consisted of 68 bone elements scattered over an area of 5 m2.[19][14] Another important site there is the natural asphalt pit of Tanque Loma on the Santa Elena peninsula, which had over 1000 individual bones. About 660 of them were examined in detail, and about 11% can be placed in Notiomastodon. These correspond to 3 individuals, including two juveniles.[92][93]

Paleoecology Large, mesoherbivorous mammals in the Brazilian Intertropical Region were widespread and diverse, including the cow-like toxodontids Toxodon platensis and Piauhytherium, the macraucheniid litoptern Xenorhinotherium and equids such as Hippidion principale and Equus neogaeus. Toxodontids were large mixed feeders as well and lived in forested areas, while the equids were nearly entirely grazers. Xenarthran fossils are present in the area as well from several different families, like the giant megatheriid ground sloth Eremotherium, the fellow scelidotheriid Valgipes, the mylodontids Glossotherium, Ocnotherium, and Mylodonopsis. Smaller ground sloths such as the megalonychids Ahytherium and Australonyx and the nothrotheriid Nothrotherium have also been found in the area. Eremotherium was a generalist, while Nothrotherium was a specialist for trees in low density forests, and Valgipes was an intermediate of the two that lived in arboreal savannahs. Glyptodonts and cingulates like the grazing glyptodonts Glyptotherium and Panochthus and the omnivorous pampatheres Pampatherium and Holmesina were present in the open grasslands. Carnivores included some of the largest known mammalian land carnivores, like the giant felid Smilodon populator and the bear Arctotherium wingei.[94][95] Several extant taxa are also known from the BIR, like guanacos, giant anteaters, collared peccaries, and striped hog-nosed skunks.[96] Two crab-eating types of extant mammals are also known from the BIR, the crab-eating raccoon and the crab-eating fox, indicating that crabs were also present in the region.[96] The environment of the BIR is unclear, as there were both several species that were grazers, but the precede of the arboreal fossil monkeys Protopithecus and Caipora in the area causes confusion over the area’s paleoenvironment. Most of Brazil was thought to have been covered in open tropical cerrado vegetation during the Late Pleistocene, but if Protopithecus and Caipora were arboreal, their presence suggests that the region may have supported a dense closed forest during the Late Pleistocene.[96][97] It is possible that the region alternated between dry open savannah and closed wet forest throughout the climate change of the Late Pleistocene.[98] ExtinctionDuring the last few thousand years of its existence, Notiomastodon was contemporary with the first human groups of hunter-gatherers that arrived in South America. Notiomastodon disappeared simultaneously with most other megafauna (large animals) in the Americas at the end of the Pleistocene as part of the Late Pleistocene megafauna extinctions, the exact causes of which are the subject of long-standing controversy in the scientific literature. By the time of the extinct It is not clear if the Paleo-Indians played a decisive role in the extinction of Notiomastodon through active hunting. In total, there are less than a dozen sites in South America where Notiomastodon is associated with human presence. These are scattered throughout the north and southwest of South America, while in the entire Pampas region there are no known finds with the joint presence of proboscideans and humans. Therefore, there is little actual evidence of active hunting. Among the most significant finds are those made in Taima Taima in the coastal area of north-central Venezuela. There, an El Jobo-type projectile point was found in a Notiomastodon skeleton, and this site also contains remains of the ground sloth Glossotherium. The age of these finds dates back to 13,000 years ago.[99][100] Some of the finds at Monte Verde in central Chile, are also associated with human hunting. The pieces found there, however, are very fragmented and frequently limited to tusks and molars as well as individual elements of the skeleton,[54][55] which is why some authors suppose that the remains of proboscideans come from corpses located in another location and were later consumed there.[101] In 2019, a description of a young specimen from Brazil was published which had an artifact lodged into its skull, providing clear evidence that this individual was hunted.[102] Some very recent finds of Notiomastodon are 11,740 to 11,100 years old and were obtained from Quereo in Chile, from Itaituba on the Tapajós River in central Brazil, and from Tibitó in Colombia, the latter being associated with three dozen tools of stone.[89][90] Even more recent is a skull from Taguatagua in Chile, estimated to be 10,300 years before present.[55] On the other hand, some scientists suggest a review of individual sites with finds dated to the early Holocene, as in Quebrada Ñuagapua in Bolivia.[103][104] A find of a gomphothere, probably Notiomastodon in Totumo, Colombia was dated as recently as 6,060 ± 60 years before present,[59] however, given how much later this date is than other finds of Notiomastodon, this date should be considered with caution without other corroboration.[105] The climatic models projected for South America during the latter Pleistocene and the early Holocene suggests that the habitats were more humid and with more presence of forests, which could reduce the suitable habitat for Notiomastodon and Equus neogeus, another species commonly found in open habitats, along with the subsequent changes in the vegetation could affect to these large mammals.[106] Notes

References

Information related to Notiomastodon |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||