|

1820 United States presidential election

Presidential elections were held in the United States from November 1 to December 6, 1820. Taking place at the height of the Era of Good Feelings, the election saw incumbent Democratic-Republican President James Monroe win reelection without a major opponent. It was the third and the most recent United States presidential election in which a presidential candidate ran effectively unopposed. James Monroe's re-election marked the first time in U.S. history that a third consecutive president won a second election. Monroe and Vice President Daniel D. Tompkins faced little to no opposition from other Democratic-Republicans in their quest for a second term. The Federalist Party had fielded a presidential candidate in each election since 1796, but the party's already-waning popularity had declined further following the War of 1812. Although able to field a nominee for vice president, the Federalists could not put forward a presidential candidate, leaving Monroe without organized opposition. Monroe won every state and received all but one of the electoral votes. Secretary of State John Quincy Adams received the only other electoral vote, which came from faithless elector William Plumer. Nine different Federalists received electoral votes for vice president, but Tompkins won re-election by a large margin. No other post-Twelfth Amendment presidential candidate has matched Monroe's electoral vote share. Monroe and George Washington remain the only presidential candidates to run without any major opposition. Monroe's victory was the last of six straight victories by Virginians in presidential elections (Jefferson twice, Madison twice, and Monroe twice). This was the last election in which an incumbent ticket was reelected until the ticket of Woodrow Wilson and Thomas R. Marshall were reelected in 1916. BackgroundDespite the continuation of single-party politics (known in this case as the Era of Good Feelings), serious issues emerged during the election in 1820. The nation had endured a widespread depression following the Panic of 1819 and momentous disagreement about the extension of slavery into the territories was taking center stage. Nevertheless, James Monroe faced no opposition party or candidate in his re-election bid, although he did not receive all of the electoral votes (see below). Massachusetts was entitled to 22 electoral votes in 1816, but cast only 15 in 1820 because of the Missouri Compromise of 1820, which made the region of Maine, long part of Massachusetts, a free state to balance the pending admission of slave state Missouri. In addition, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, and Mississippi also cast one fewer electoral vote than they were entitled to, as one elector from each state died before the electoral meeting. Consequently, this meant that Mississippi cast only two votes when any state is always entitled to a minimum of three. This is one of only three times a state or district has cast under the minimum of three electoral votes, the others being Nevada in 1864 and the District of Columbia in 2000. In the case of the former, an elector was snowbound and there was no law to replace him (Nevada had only become a state that year). In that of the latter, a faithless elector abstained from voting. Alabama, Illinois, Maine, Mississippi, and Missouri participated in their first presidential election in 1820, Missouri came with controversy since it was not yet officially a state (see below). No new states would participate in American presidential elections until 1836, after the admission to the Union of Arkansas in 1836 and Michigan in 1837 (after the main voting, but before the counting of the electoral vote in Congress).[2] NominationsDemocratic-Republican Party nomination

Only fifty of the one hundred ninety-one Democratic-Republican members of the United States Congress attended the nominating caucus and they unanimously voted to not make a nomination as it would be unnecessary to do so. Monroe and Tompkins appeared on the ballot with the support of the Democratic-Republican Party despite not being formally nominated.[3] General electionCampaignMonroe's re-election in 1820, while notable for its broad support, was not without opposition nor did there exist a unanimity of sentiment in favor of President Monroe. Complaints of Monroe's administration included his opposition to federal funds in constructing internal improvements, his failure to advocate a substantial increase in the tariff, his failure to champion the cause of the South in the Missouri Controversy, and his failure to champion the cause of the North in the Missouri Controversy.[4] Despite these criticisms, Monroe received backing from both Democratic-Republican and Federalist elector candidates in most states. In many cases, rival Democratic-Republicans vied for the privilege of casting their electoral vote for Monroe. True opposition to Monroe's presidency only emerged in New York and Pennsylvania where New York Governor DeWitt Clinton was supported as an alternative presidential candidate.[5] Federal fundingMonroe's opposition to federal funds in constructing internal improvements and his apparent neutrality on the tariff issue were especially displeasing to Kentucky and the Middle Atlantic states. In early 1819, the Kentucky Gazette vigorously endorsed the idea of federal internal improvements, condemning Monroe for his position on the issue. Later, commenting on Monroe's pending visit to Lexington, the Kentucky Gazette said:[4]

After Monroe's visit, the Gazette, once more returning to the issue of internal improvements, noted that the President had been emphatically told during his stay in Kentucky that the people of the state were not in sympathy with his position on that question.[4] Opposition to Monroe on the issue was also present in New York where the Clintonian faction of the Democratic-Republicans deeply resented Monroe on the matter with Governor Clinton even expressing disappointment as early as 1817. The two men were not on friendly terms since the latter's campaign against the party in the 1812 presidential election. This conflict openly erupted after the Clintonians accused the Monroe administration of using patronage to defeat Clinton in his campaign for re-election. When it came to the time of choosing electors, the Bucktail faction of the Democratic-Republicans, which was loyal to Monroe, and the Clintonians ran rival tickets. Newspapers referred to the former as the "slave ticket" and the latter as the "anti-slave ticket".[4] Ultimately, the Clintonian faction lost, with the legislature voting 89 for the Bucktail ticket, 53 for the Clintonian ticket, and 1 not voting.[5] The Columbian, the Clintonian organ in New York City, claimed that its candidates would have voted for Monroe had they won. However, it is likely that some would have supported Clinton instead.[4] Tariff policyIt was in Pennsylvania that the greatest criticism of Monroe's tariff policy, or lack of a tariff policy, was encountered and where the most spirited opposition to Monroe existed. The Panic of 1819, with its disastrous effects on many factories in the state, produced a strong demand for higher protective tariffs. A public meeting held in Philadelphia in August 1819 declared that it would vote for no one for public office who was known to be unfriendly to the principle of tariff protection. This opposition to Monroe was spearheaded by William Duane and his newspaper the Philadelphia Auror. Duane, though a Democratic-Republican, had been for years a severe critic of both the state and national leadership of the party. In 1820 the Aurora's anonymous correspondent, BRUTUS (suspected to be Duane himself), began to denounce Monroe as the champion of slavery, blamed him for causing the defeat of the tariff bill of 1820, blamed him for discouraging internal improvements, and accused him of championing the cause of the national bank, favoring the caucus system, and even encouraging the Supreme Court to render corrupt decisions.[4] On October 21, a public meeting was held in Philadelphia to nominate anti-Monroe electoral candidates. The meeting was contentious, with the Pro-Monroe Philadelphia Democratic Press and the Aurora offering conflicting accounts. The Democratic Press claimed that Monroe supporters were so numerous at the State House's Mayor's Court Room that the opposition had to move to Overholt's Tavern. In contrast, the Aurora described the meeting, which was said to have been largely made up of Quakers, as impressive but disrupted by unruly Monroe supporters, leading many Quakers to withdraw in dismay as they were not accustomed to such turmoil.[4] The newly formed anti-Monroe ticket pledged support for Clinton as president and campaigned briefly in Philadelphia, though the rest of the state remained largely indifferent. The Aurora vehemently attacked Monroe as a candidate who supported slavery and urged Pennsylvania to break from their vassalage to the "slave aristocracy." On the eve of the election, BRUTUS (the anonymous source mentioned above) denounced Monroe as an enemy of internal improvements and domestic manufacturing, while praising Governor Clinton's support for these initiatives.[4] When the election returns were counted it was found that Monroe had received 1,233 votes in Philadelphia to 793 for Clinton. Elsewhere in Pennsylvania, Clinton's support was minimal, with only Fayette County breaking 10% of the vote for Clinton electors.[4][6] Missouri Compromise and VirginiaUnexpected opposition to Monroe came from his very own state of Virginia. In February 1820, when the Virginia legislative caucus met to nominate presidential electors just as the Missouri Compromise was being finalized, it was clear that Monroe wouldn't veto the compromise as it was seen as the only peaceful solution to the slavery issue within the Union. However, while Northern moderates urged Monroe to accept the compromise, Virginia Democratic-Republicans, led by the Richmond Enquirer, demanded that the South resist any restrictions on slavery in Missouri or other territories. As such, the Virginia caucus was dismayed to hear rumors that Monroe supported a compromise allowing slavery in Missouri but prohibiting it in the Louisiana Territory above the Parallel 36°30′ north. Angered, the caucus adjourned without making nominations. Virginians, including Henry St. George Tucker, wrote furious letters to Washington, condemning the compromise and expressing their unwillingness to support Monroe if it meant sacrificing Southern rights. Monroe, usually mild-mannered, grew indignant at these criticisms. He wrote to his son-in-law, George Hay, emphasizing that principles were more important than expediency and suggesting that if the legislators preferred another candidate, they should say so. Instead, the caucus reconvened on February 17 and nominated Monroe supporters for the electoral college, likely realizing their earlier mistake. Hay selectively shared favorable letters from Monroe with the caucus, hinting at a possible compromise. Eventually, Monroe approved the Missouri Compromise, despite earlier considering a veto.[4] DisputesOn March 9, 1820, Congress had passed a law directing Missouri to hold a convention to form a constitution and a state government. This law stated that "the said state, when formed, shall be admitted into the Union, upon an equal footing with the original states, in all respects whatsoever."[7] However, when Congress reconvened in November 1820, the admission of Missouri became an issue of contention. Proponents claimed that Missouri had fulfilled the conditions of the law and therefore was a state; detractors contended that certain provisions of the Missouri Constitution violated the United States Constitution. By the time Congress was due to meet to count the electoral votes from the election, this dispute had lasted over two months. The counting raised a problem: if Congress counted Missouri's votes, that would count as recognition that Missouri was a state; on the other hand, if Congress failed to count Missouri's vote, it would count as recognition that Missouri was not a state. Knowing ahead of time that Monroe had won in a landslide and that Missouri's vote would therefore make no difference in the final result, the Senate passed a resolution on February 13, 1821, stating that if a protest were made, there would be no consideration of the matter unless the vote of Missouri would change who would become president. Instead, the president of the Senate would announce the final tally twice, once with Missouri included and once with it excluded.[8] The next day this resolution was introduced in the full House. After a lively debate, it was passed. Nonetheless, during the counting of the electoral votes on February 14, 1821, an objection was raised to the votes from Missouri by Representative Arthur Livermore of New Hampshire. He argued that since Missouri had not yet officially become a state, it had no right to cast any electoral votes. Immediately, Representative John Floyd of Virginia argued that Missouri's votes must be counted. Chaos ensued, and order was restored only with the counting of the vote as per the resolution and then adjournment for the day.[9] Results Popular voteThe Federalists received a small amount of the popular vote despite having no electoral candidates. Even in Massachusetts, where the Federalist slate of electors was victorious, the electors cast all of their votes for Monroe. This was the first election in which the Democratic-Republicans won in Connecticut and Delaware.

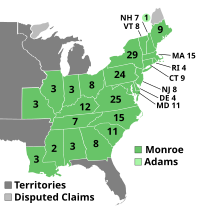

Source (Electoral Vote): "Electoral College Box Scores 1789–1996". National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved July 30, 2005. Source (Popular Vote): A New Nation Votes: American Election Returns 1787-1825[10] (a) Only 15 of the 24 states chose electors by popular vote. Electoral vote The sole electoral vote against Monroe came from William Plumer, an elector from New Hampshire and former United States senator and New Hampshire governor. Plumer cast his electoral ballot for Secretary of State John Quincy Adams. Everett S. Brown, a political scientist, noted that Plumer had asked his son, William Plumer Jr., to see if Adams had objections to Plumer casting his vote for him.[11] While legend has it this was to ensure that George Washington would remain the only American president unanimously chosen by the Electoral College, that was not Plumer's goal. In fact, Plumer simply thought that Monroe was a mediocre president and that Adams would be a better one.[12] Plumer also refused to vote for Tompkins for Vice President as "grossly intemperate", not having "that weight of character which his office requires," and "because he grossly neglected his duty" in his "only" official role as President of the Senate by being "absent nearly three-fourths of the time";[13] Plumer ultimately voted for Adams for president and Richard Rush for vice president; in doing so, Plumer unwittingly prefigured the National Republican ticket that Adams and Rush would run on together in 1828.[14] In response to Plumer's vote, Adams felt "surprise and mortification", and that Plumer's vote was an affront to the Monroe administration.[15] Even though every member of the Electoral College was pledged to Monroe, there were still a number of Federalist electors who voted for a Federalist vice president rather than Monroe's running mate Daniel D. Tompkins: those for Richard Stockton came from Massachusetts, while the entire Delaware delegation voted for Daniel Rodney for vice president, and Robert Goodloe Harper's vice presidential vote was cast by an elector from his home state of Maryland. In any case, these breaks in ranks were not enough to deny Tompkins a substantial electoral college victory. Monroe's share of the electoral vote has not been exceeded by any candidate since, with the closest competition coming from Franklin D. Roosevelt's landslide 1936 victory. Only Washington, who won the vote of each presidential elector in the 1789 and 1792 presidential elections, can claim to have swept the Electoral College.

Source: "Electoral College Box Scores 1789–1996". National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved July 30, 2005. (a) There was a dispute over the validity of Missouri's electoral votes, due to the timing of its assumption of statehood. The first figure excludes Missouri's votes and the second figure includes them. Maps

Results by stateElections in this period were vastly different from modern-day presidential elections. The actual presidential candidates were rarely mentioned on tickets and voters were voting for particular electors who were pledged to a particular candidate. There was sometimes confusion as to who a particular elector was actually pledged to. Results are reported as the highest result for an elector for any given candidate. For example, if three Monroe electors received 100, 50, and 25 votes, Monroe would be recorded as having 100 votes. Confusion surrounding the way results are reported may lead to discrepancies between the sum of all state results and national results. In Massachusetts, Federalist electors won 62.06% of the vote. However, only 7,902 of these votes went to Federalist electors who did not cast their votes for Monroe (this being most likely because these Federalist electors lost). Similarly, In Kentucky, 1,941 ballots were cast for an elector labelled as Federalist who proceeded to vote for Monroe. All of the Federalist Monroe votes have been placed in the Federalist column, as the Federalist party fielded no presidential candidate and therefore it is likely these electors simply cast their votes for Monroe because the overwhelming majority he achieved made their votes irrelevant.

States that flipped from Federalist to Democratic-RepublicanElectoral college selection

See also

Footnotes

References

Bibliography

External linksWikimedia Commons has media related to United States presidential election, 1820.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||