|

Arabian Sea

The Arabian Sea (Arabic: بَحرُ ٱلْعَرَبْ, romanized: baḥr al-ʿarab)[1] is a region of sea in the northern Indian Ocean, bounded on the west by the Arabian Peninsula, Gulf of Aden and Guardafui Channel, on the northwest by Gulf of Oman and Iran, on the north by Pakistan, on the east by India, and on the southeast by the Laccadive Sea[2] and the Maldives, on the southwest by Somalia.[3] Its total area is 3,862,000 km2 (1,491,000 sq mi) and its maximum depth is 5,395 meters (17,700 feet). The Gulf of Aden in the west connects the Arabian Sea to the Red Sea through the strait of Bab-el-Mandeb, and the Gulf of Oman is in the northwest, connecting it to the Persian Gulf. GeographyThe Arabian Sea's surface area is about 3,862,000 km2 (1,491,130 sq mi).[4] The maximum width of the sea is approximately 2,400 km (1,490 mi), and its maximum depth is 5,395 metres (17,700 ft).[5] The biggest river flowing into the sea is the Indus River. The Arabian Sea has two important branches: the Gulf of Aden in the southwest, connecting with the Red Sea through the strait of Bab-el-Mandeb; and the Gulf of Oman to the northwest, connecting with the Persian Gulf. There are also the gulfs of Khambhat and Kutch on the Indian Coast. The Arabian Sea has been crossed by many important marine trade routes since the 3rd or 2nd millennium BCE. Major seaports include Kandla Port, Mundra Port, Pipavav Port, Dahej Port, Hazira Port, Mumbai Port, Nhava Sheva Port (Navi Mumbai), Mormugão Port (Goa), New Mangalore Port and Kochi Port in India, the Port of Karachi, Port Qasim, and the Gwadar Port in Pakistan, Chabahar Port in Iran and the Port of Salalah in Salalah, Oman. The largest islands in the Arabian Sea include Socotra (Yemen), Masirah Island (Oman), Lakshadweep (India) and Astola Island (Pakistan). The countries with coastlines on the Arabian Sea are Yemen, Oman, Pakistan, Iran, India and the Maldives.[4] LimitsThe International Hydrographic Organization defines the limits of the Arabian Sea as follows:[6]

HydrographyThe International Indian Ocean Expedition in 1959 was among the first to perform hydrographic surveys of the Arabian Sea. Significant bathymetric surveys were also conducted by the Soviet Union during the 1960s.[7] Hydrographic featuresSignificant features in the northern Arabian Sea include the Indus Fan, the second largest fan system in the world. The De Covilhao Trough, named after the 15th century Portuguese explorer Pero de Covilhăo, reaches depths of 4,400 metres (14,436 ft) and separates the Indus Fan region from the Oman Abyssal Plain, which eventually leads to the Gulf of Oman. The southern limits are dominated by the Arabian Basin, a deep basin reaching depths over 4,200 metres (13,780 ft). The northern sections of the Carlsberg Ridge flank the southern edge of the Arabian Basin. The deepest parts of the Arabian Sea are in the Alula-Fartak Trough on the western edge of the Arabian Sea off the Gulf of Aden. The trough, reaching depths over 5,360 metres (17,585 ft), traverses the Gulf of Aden and the Arabian Sea. The deepest known point is in the Arabian Sea limits at a depth of 5,395 metres (17,700 ft). Other significant deep points are part of the Arabian Basin, which include a 5,358 metres (17,579 ft) deep point off the northern limit of Calrsberg Ridge.[8] SeamountsProminent sea mounts off the Indian west coast include Raman Seamount named after C. V. Raman, Panikkar Seamount, named after N. K. Panikkar, and the Wadia Guyot, named after D. N. Wadia.[9] Sind'Bad Seamount, named after the fictional explorer Sinbad the Sailor, Zheng He Seamount, and the Mount Error Guyot are some notable sea mounts in western Arabian Sea.[10][11] Border and basin countriesBorder and basin countries:[12][13]

Alternative names

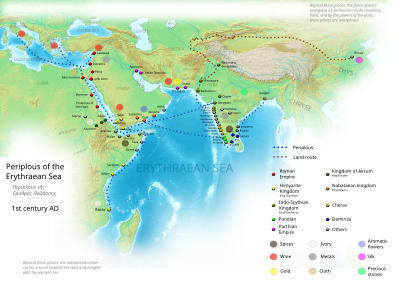

The Arabian Sea historically and geographically has been referred to with different names by Arabian and European geographers and travelers, including Erythraean Sea, Indian Sea, Oman sea,[14] Erythraean, Persian Sea in para No 34-35 of the Voyage.[15] In Indian folklore, it is referred to as Darya, Sindhu Sagar, Arab Samudra.[16][17][18] Arab geographers, sailors and nomads used to call this sea by different names, including the Akhdar (Green) Sea, Bahre Fars (Persian Sea), the Ocean Sea, the Hindu sea, the Makran Sea, the sea of Oman; among them Zakariya al-Qazwini, Al-Masudi, Ibn Hawqal and Hafiz-i Abru. They wrote: "The green sea and Indian sea and Persian sea are all one sea and in this sea there are strange creatures." in Iran and Turkey people call it Oman sea.[19] In the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, as well as in some ancient maps, Erythraean Sea refers to the whole area of the northwestern Indian Ocean, including the Arabian Sea.[20]

Trade routes The Arabian Sea has been an important marine trade route since the era of the coastal sailing vessels from possibly as early as the 3rd millennium BCE, certainly the late 2nd millennium BCE through the later days known as the Age of Sail. By the time of Julius Caesar, several well-established combined land-sea trade routes depended upon water transport through the sea around the rough inland terrain features to its north. These routes usually began in the Far East or down river from Madhya Pradesh, India with transshipment via historic Bharuch (Bharakuccha), traversed past the inhospitable coast of modern-day Iran, then split around Hadhramaut, Yemen into two streams north into the Gulf of Aden and thence into the Levant, or south into Alexandria via Red Sea ports such as Axum. Each major route involved transhipping to pack animal caravan, travel through desert country and risk of bandits and extortionate tolls by local potentates. This southern coastal route past the rough country in the southern Arabian Peninsula was significant, and the Egyptian Pharaohs built several shallow canals to service the trade, one more or less along the route of today's Suez Canal, and another from the Red Sea to the Nile River, both shallow works that were swallowed up by huge sand storms in antiquity. Later the kingdom of Axum arose in Ethiopia to rule a mercantile empire rooted in the trade with Europe via Alexandria. [21] Major portsJawaharlal Nehru Port in Mumbai is the largest port in the Arabian Sea, and the largest container port in India. Major Indian ports in the Arabian Sea are Mundra Port, Kandla Port, Nava Sheva, Kochi Port, Mumbai Port, Vizhinjam International Seaport Thiruvananthapuram and Mormugão.[22][23]  The Port of Karachi, Pakistan's largest and busiest seaport lies on the coast of the sea. It is located between the Karachi towns of Kiamari and Saddar. The Gwadar Port of Pakistan is a warm-water, deep-sea port situated at Gwadar in Balochistan at the apex of the Arabian Sea and at the entrance of the Persian Gulf, about 460 km west of Karachi and approximately 75 km (47 mi) east of Pakistan's border with Iran. The port is located on the eastern bay of a natural hammerhead-shaped peninsula jutting out into the Arabian Sea from the coastline. Port of Salalah in Salalah, Oman is also a major port in the area. The International Task Force often uses the port as a base. There is a significant number of warships of all nations coming in and out of the port, which makes it a very safe bubble. The port handled just under 3.5m teu in 2009.[24] Islands There are several islands in the Arabian Sea, with the most important ones being Lakshadweep Islands (India), Socotra (Yemen), Masirah (Oman) and Astola Island (Pakistan). The Lakshadweep Islands (formerly known as the Laccadive, Minicoy, and Aminidivi Islands) is a group of islands in the Laccadive Sea region of Arabian Sea, 200 to 440 km (120 to 270 mi) off the southwestern coast of India. The archipelago is a union territory and is governed by the Union Government of India. The islands form the smallest union territory of India with their total surface area being just 32 km2 (12 sq mi). Next to these islands are the Maldives islands. These islands are all part of the Lakshadweep-Maldives-Chagos group of islands. Zalzala Koh was an island which was around for only a few years. After the 2013 earthquake in Pakistan, the mud island was formed. By 2016 the island had completely submerged.[25] Astola Island, also known as Jezira Haft Talar in Balochi, or 'Island of the Seven Hills', is a small, uninhabited island in the northern tip of the Arabian Sea in Pakistan's territorial waters. Socotra, also spelled Soqotra, is the largest island, being part of a small archipelago of four islands. It lies some 240 km (150 mi) east of the Horn of Africa and 380 km (240 mi) south of the Arabian Peninsula. Masirah and the five Khuriya Muriya Islands are islands off the southeastern coast of Oman. Major coastal citiesOxygen minimum zone The Arabian Sea has one of the world's three largest oceanic oxygen minimum zones (OMZ), or “dead zones,” along with the eastern tropical North Pacific and the eastern tropical South Pacific. OMZs have very low levels of oxygen, sometimes so low as to be undetectable by standard equipment.[26] The Arabian Sea's OMZ has the lowest levels of oxygen in the world, especially in the Gulf of Oman.[27] Causes of the OMZ may include untreated sewage as well as high temperatures on the Indian subcontinent, which increase winds blowing towards India, bringing up nutrients and reducing oxygen in the Arabian Sea's waters. In winter, phytoplankton suited to low-oxygen conditions turn the OMZ bright green.[28] Environment and wildlifeThe wildlife of the Arabian sea is diverse, and entirely unique because of the geographic distribution.

Arabian Sea warmingRecent studies[29][30][31] by the Indian Institute of Tropical Meteorology confirmed that the Arabian Sea is warming monotonously; it possibly is due to global warming. The intensification and northward shift of the summer monsoon low-level jet over the Arabian Sea from 1979 to 2015, led to increased upper ocean heat content due to enhanced downwelling and reduced southward heat transport.[32] Native namesRegional endonyms for the Arabian sea in languages of the coastal regions surrounding it.

See alsoReferences

SourcesThis article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Arabian Sea". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. External linksWikimedia Commons has media related to Arabian Sea. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||