|

Jesus (name)

Jesus (/ˈdʒiːzəs/) is a masculine given name derived from Iēsous (Ἰησοῦς; Iesus in Classical Latin) the Ancient Greek form of the Hebrew name Yeshua (ישוע).[1][2] As its roots lie in the name Isho in Aramaic and Yeshua in Hebrew, it is etymologically related to another biblical name, Joshua.[3] The vocative form Jesu, from Latin Iesu, was commonly used in religious texts and prayers during the Middle Ages, particularly in England, but gradually declined in usage as the English language evolved. Jesus is usually not used as a given name in the English-speaking world, while its counterparts have had longstanding popularity among people with other language backgrounds, such as the Spanish Jesús. Etymology

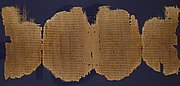

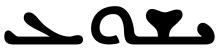

Linguistic analysisThere have been various proposals as to the literal etymological meaning of the name Yəhôšuaʿ (Joshua, Hebrew: יְהוֹשֻׁעַ), including Yahweh/Yehowah saves, (is) salvation, (is) a saving-cry, (is) a cry-for-saving, (is) a cry-for-help, (is) my help.[4][5][6][7] A recent study proposes that the name should be understood as "Yahweh is lordly".[8] Yehoshua–Yeshua–Iēsous–IESVS–Iesu–JesusThis early biblical Hebrew name יְהוֹשֻׁעַ (Yehoshuaʿ) underwent a shortening into later biblical יֵשׁוּעַ (Yeshuaʿ), as found in the Hebrew text of verses Ezra 2:2, 2:6, 2:36, 2:40, 3:2, 3:8, 3:9, 3:10, 3:18, 4:3, 8:33; Nehemiah 3:19, 7:7, 7:11, 7:39, 7:43, 8:7, 8:17, 9:4, 9:5, 11:26, 12:1, 12:7, 12:8, 12:10, 12:24, 12:26; 1 Chronicles 24:11; and 2 Chronicles 31:15 – as well as in Biblical Aramaic at verse Ezra 5:2. These Bible verses refer to ten individuals (in Nehemiah 8:17, the name refers to Joshua son of Nun). This historical change may have been due to a phonological shift whereby guttural phonemes weakened, including [h].[9] Usually, the traditional theophoric element יהו (Yahu) was shortened at the beginning of a name to יו (Yo-), and at the end to יה (-yah). In the contraction of Yehoshuaʿ to Yeshuaʿ, the vowel is instead fronted (perhaps due to the influence of the y in the triliteral root y-š-ʿ). Yeshua was in common use by Jews during the Second Temple period and many Jewish religious figures bear the name, including Joshua in the Hebrew Bible and Jesus in the New Testament.[2][1] During the post-biblical period the further shortened form Yeshu was adopted by Hebrew speaking Jews to refer to the Christian Jesus, however Yehoshua continued to be used for the other figures called Jesus.[10] However, both the Western and Eastern Syriac Christian traditions use the Aramaic name ܝܫܘܥ (in Hebrew script: ישוע) Yeshuʿ and Yishoʿ, respectively, including the ʿayin.[11] The name Jesus is derived from the Hebrew name Yeshua, which is based on the Semitic root y-š-ʕ (Hebrew: ישע), meaning "to deliver; to rescue."[12][13][14] Likely originating in proto-Semitic (yṯ'), it appears in several Semitic personal names outside of Hebrew, as in the Aramaic name Hadad Yith'i, meaning "Hadad is my salvation". Its oldest recorded use is in an Amorite personal name from 2048 B.C.[15] By the time the New Testament was written, the Septuagint had already transliterated ישוע (Yeshuaʿ) into Koine Greek as closely as possible in the 3rd-century BCE, the result being Ἰησοῦς (Iēsous). Since Greek had no equivalent to the Semitic letter ש shin [ʃ], it was replaced with a σ sigma [s], and a masculine singular ending [-s] was added in the nominative case, in order to allow the name to be inflected for case (nominative, accusative, etc.) in the grammar of the Greek language. The diphthongal [a] vowel of Masoretic Yehoshuaʿ or Yeshuaʿ would not have been present in Hebrew/Aramaic pronunciation during this period, and some scholars believe some dialects dropped the pharyngeal sound of the final letter ע ʿayin [ʕ], which in any case had no counterpart in ancient Greek. The Greek writings of Philo of Alexandria[16] and Josephus frequently mention this name. In the Panarion of Epiphanius of Salamis, the name Iēsous comes from Hebrew/Aramaic and means "healer or physician, and saviour," and that the earliest Christians were named Jessaeans based on this name before they were called Christians. This etymology of 'physician' may derive from the sect of the θεραπευταί (Therapeutae), of which Ephanius was familiar.[17] From Greek, Ἰησοῦς (Iēsous) moved into Latin at least by the time of the Vetus Latina. The morphological jump this time was not as large as previous changes between language families. Ἰησοῦς (Iēsous) was transliterated to Latin IESVS, where it stood for many centuries. The Latin name has an irregular declension, with a genitive, dative, ablative, and vocative of Jesu, accusative of Jesum, and nominative of Jesus. Minuscule (lower case) letters were developed around 800 and some time later the U was invented to distinguish the vowel sound from the consonantal sound and the J to distinguish the consonant from I. Similarly, Greek minuscules were invented about the same time, prior to that the name was written in capital letters (ΙΗϹΟΥϹ) or abbreviated as (ΙΗϹ) with a line over the top, see also Christogram. Modern English Jesus derives from Early Middle English Iesu (attested from the 12th century). The name participated in the Great Vowel Shift in late Middle English (15th century). The letter J was first distinguished from 'I' by the Frenchman Pierre Ramus in the 16th century, but did not become common in Modern English until the 17th century, so that early 17th century works such as the first edition of the King James Version of the Bible (1611) continued to print the name with an I.[18] From the Latin, the English language takes the forms Jesus (from the nominative form), and Jesu (from the vocative and oblique forms). Jesus is the predominantly used form, while Jesu lingers in some more archaic religious texts. DeclensionIn both Latin and Greek, the name is declined irregularly:[citation needed]

Biblical references The name Jesus (Yeshua) appears to have been in use in the Land of Israel at the time of the birth of Jesus.[2][19] Moreover, Philo's reference in Mutatione Nominum item 121 to Joshua (Ἰησοῦς) meaning salvation (σωτηρία) of the Lord indicates that the etymology of Joshua was known outside Israel.[20] Other figures named Jesus include Jesus Barabbas, Jesus ben Ananias and Jesus ben Sirach. In the New Testament, in Luke 1:31 an angel tells Mary to name her child Jesus, and in Matthew 1:21 an angel tells Joseph to name the child Jesus during Joseph's first dream. Matthew 1:21 indicates the salvific implications of the name Jesus when the angel instructs Joseph: "you shall call his name Jesus, for he will save his people from their sins".[21][22] It is the only place in the New Testament where "saves his people" appears with "sins".[23] Matthew 1:21 provides the beginnings of the Christology of the name Jesus. At once it achieves the two goals of affirming Jesus as the savior and emphasizing that the name was not selected at random, but based on a heavenly command.[24] Other usageMedieval English and JesusJohn Wycliffe (1380s) used the spelling Ihesus and also used Ihesu ('J' was then a swash glyph variant of 'I', not considered to be a separate letter until the 1629 Cambridge 1st Revision King James Bible where "Jesus" first appeared) in oblique cases, and also in the accusative, and sometimes, apparently without motivation, even for the nominative. Tyndale in the 16th century has the occasional Iesu in oblique cases and in the vocative; The 1611 King James Version uses Iesus throughout, regardless of syntax. Jesu came to be used in English, especially in hymns. Jesu (/ˈdʒiːzuː/ JEE-zoo; from Latin Iesu) is sometimes used as the vocative of Jesus in English. The oblique form, Iesu, came to be used in Middle English. Other languages In East Scandinavian, German and several other languages, the name Jesus is used. Some other language usage is as follows:

See alsoReferences

Bibliography

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||